Botnet

What is a Botnet?

A shortening of the term “robot network,” a botnet is a network of compromised devices used to perform malicious tasks. A compromised device can be any device that’s Internet accessible—things like computers, mobile phones, smart-home devices, even routers and servers. Often these devices are owned by private individuals, and have become compromised without the owner’s knowledge. A botnet can be used for activities like sending spam email, installing malware to steal login credentials, or cyberattacks on businesses or governments.

Initially, a device is infected with malware that allows a remote operator (called a “bot herder”) to communicate with the infected device. Both the malware program and the infected device are referred to as a “bot,” and a collection of infected devices working in unison is a “botnet.” A botnet can contain thousands or millions of bots, and can sit idle and undetected until the bot herder activates it for a specific purpose.

How is a botnet created?

There are two common botnet structures that bot herders use today. The original structure of the first botnets was a centralized architecture. In a centralized arrangement, a bot herder uses a single controller (such as a website or other communication protocol) to pass down commands directly to all bots. When the bots complete their assigned task, they in turn report back to the controller. This format has become less popular over time because the single controller is easy to locate and shut down, effectively disabling the entire botnet.

Today, many botnets are built using a decentralized, peer-to-peer, structure. In a peer-to-peer arrangement, bots on the botnet are interconnected—they communicate directly with one another rather than a central controller. The bot herder only has to communicate with any one bot, and that bot will communicate to its neighbors on the network, and so on until all bots have the assignment. A decentralized botnet is very difficult to shut down. The web-like structure makes it harder to locate the bot herder because their device looks the same as any other bot. You can disable individual bots, but the rest will still function as a botnet.

For either structure, the first step is infection. The bot malware is installed on targeted devices by leveraging a security flaw in some software, or through things like phishing or other social engineering ploys. The initial malware usually includes instructions for the bot to check in periodically with the bot herder or neighboring bots for updates.

When the bot herder is ready to deploy the botnet, the task-specific programming is provided through these open communication channels. Open communications between a bot herder and individual bots mean instructions can change multiple times. A botnet can be built without having a specific goal in mind—its task can be set later, and changed as needed.

In recent botnet builds, the bots propagate themselves by infecting other devices on their local networks. Botnets are always looking to expand, both to increase numbers for more effective botnet attacks, and to recoup losses as bots are lost to detection/shut-down efforts.

What are botnets used for?

A bot herder may use the botnet for their own purposes. But more often the botnet is rented out to a third party, usually by the hour. Both individuals and large organizations are potential victims of botnet attacks.

Individuals can be targeted by botnet attacks that:

- Send spam email, including phishing campaigns: A large botnet is able to send millions of spam emails a day.

- Install malware: Although the initial bot infection only installs a program to establish communication with the bot, these channels can be used later to install additional malware on the infected devices—things like ransomware, keyloggers, or other spyware. This second layer of malware is used to steal sensitive data, perhaps leading to financial theft.

- Use a person’s computer to mine cryptocurrency: Mining cryptocurrency is time consuming and expensive because it requires large amounts of processing and energy. By using a botnet, the time to completion is shortened and the energy costs are borne by the owners of the infected bot devices.

Large organizations can be targeted by botnet activities, such as:

- Cyberattacks like distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks: A DDoS attack uses the botnet to flood a server with requests, overwhelming the server’s capacity and causing it to shut down. The larger the botnet, the more likely a DDoS attack will succeed.

- Creating false Internet traffic: A botnet can boost click counts for ad revenue (ad fraud) or to inflate popularity measurements (click fraud).

- Guessing system passwords using brute force: When one device tries repeatedly to log in, a system is likely to notice. But it’s more difficult to detect when many different devices are trying.

Botnets and law enforcement

Botnets are generally illegal worldwide, not only in what they’re used for, but because they’re based on unauthorized access to a person’s device. Botnets are considered a serious security threat to the Internet.

Enforcement efforts are generally ineffective—a “drop in the bucket” compared to the enormity of the problem. A centralized botnet can be shut down by finding the central controller, or by cutting off domains used to communicate so bots can’t receive instructions. But even finding—and shutting down—a centralized server to disable the botnet won’t repair the individually compromised devices.

There’s no good approach against peer-to-peer botnets. Their decentralized nature means that there’s no weak spot to target. Unless the entire network is disabled—a nearly impossible feat—there will always be a piece of the botnet to continue functioning and growing.

How to protect your devices

It can be hard to tell if your device is a bot. You may notice system resources are stretched—low memory, device performing sluggishly, slow internet response because the botnet activity is hogging bandwidth. Some botnets will protect themselves by hampering your ability to run system updates. Other than these symptoms, botnet activity leaves little evidence. The best approach is to take steps to protect your devices from becoming part of a botnet in the first place:

- Keep antivirus software on your computer updated to protect against malware downloads.

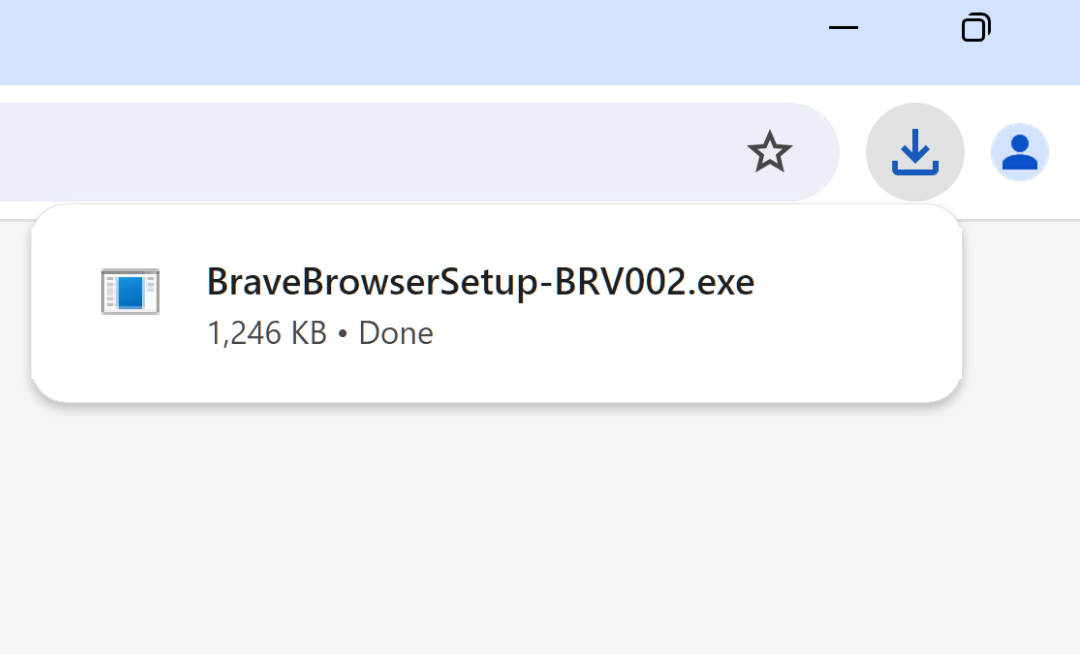

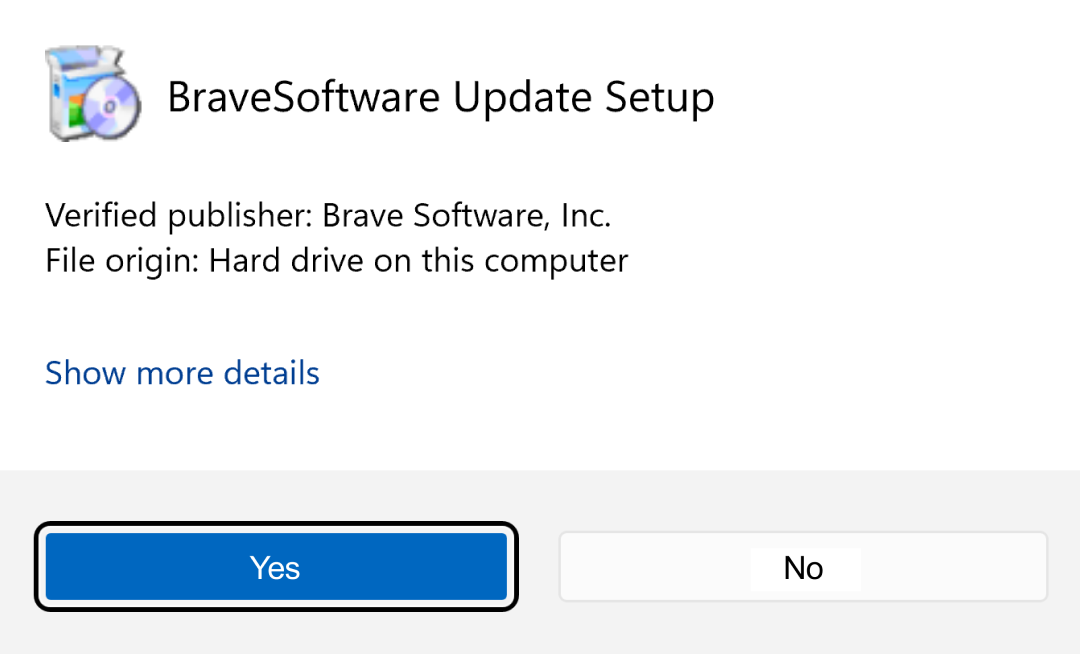

- Keep other software updated, as these updates can include security improvements. This is especially important for your operating system (OS) and browser, which will often let you know when they need to be updated.

- On mobile devices, only install apps from the official app store. On desktop or laptop devices, only install apps and extensions from the official store, or from reputable companies.

- Enable Safe Browsing in your Web browser. All major browsers, including Brave, support this feature, which can warn you if you’re about to visit a known phishing site where malware might lurk.

- Create different passwords for each login. Use a password manager to securely store all your passwords, and to generate random, unique passwords for every account and website you access.

- Be wary of any website, email, or text message that unexpectedly offers you an award, or says you need to download or update software.

- Update default passwords that come with smart devices. A device with the factory default password is easy to hijack for a botnet.

- If you think your smart device is performing poorly and may be infected, run a factory reset.