zkLogin: when ZKP is not enough

Lessons from a Real-World Zero-Knowledge Authorization System

Joint work with Sofía Celi (Brave), Hamed Haddadi (Brave Software & Imperial College London), Kyle Den Hartog (Brave). This post was written by Brave’s Security Researcher, Sofía Celi. The work is based on: https://eprint.iacr.org/2026/227

Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) are increasingly promoted as a foundational building block for privacy-preserving authentication and authorization systems. Recent proposals (particularly targeting integration into blockchain wallets, identity frameworks, and verifiable credential ecosystems) assert that ZKPs enable users to demonstrate ownership of externally issued documents without disclosing the documents themselves. Through this mechanism, such systems claim to enhance users’ accessibility, privacy and security. In these systems, a user receives an external digitally signed document, and then produces a ZKP attesting that the document satisfies some authorization process and a valid signature. The verifier relies solely on the proof (and public parts of the document), without ever seeing the underlying complete document. We refer to those systems as Zero-Knowledge Authorization.

One example of such a system is zkLogin, a widely deployed protocol. zklogin enables a user to authorize transactions, in the blockchain context, using a proof of possession of a signed JSON Web Token (JWT) issued through an OpenID Connect (OIDC) login flow. In this architecture, the JWT is treated as a root of trust: the user proves in zero knowledge that the token contains certain claims and carries a valid signature under an accepted OIDC identity provider. The verifier, often a smart contract, accepts the proof as an authorization credential, even though it never sees the full JWT.

At first glance, the security story appears straightforward for this protocol: if the used ZKP algorithm is secure and the OIDC issuer’s signature is valid, then authorization of actions should be secure and privacy preserving. However, this narrative implicitly assumes that the credential being proven about is itself well-defined, valid, canonical, and semantically robust. It also assumes that there is a strong link between the issuer, application that received the documents, user of the application, and machine that generates the ZKP proofs. But what happens when ZKPs are bolted onto messy, real-world authentication infrastructure?

Here (and in the full paper at: https://eprint.iacr.org/2026/227), we show that these issues are not mere curiosities or implementation concerns, but vulnerabilities of zklogin’s current architecture and overall system. We identify three broad classes of vulnerabilities in the system:

-

zklogin implicitly relies on externally issued JSON-based documents that can have ambiguous and non-canonical semantics, despite neither enforcing full JSON validity nor specifying a canonical parsing model.

-

The system transforms short-lived bearer authentication documents into durable authorization credentials, amplifying reliance on issuer trust while weakening scope binding, replay protection, and temporal validity enforcement.

-

zklogin introduces privacy and governance risks by recentralizing trust in a small set of issuers and outsourced infrastructure, and by exposing user identity attributes to third-party services outside the original consent relationship.

What we found out shows that the security of this system (and related ones) cannot only follow from the ZKPs alone. Instead, it critically depends on external assumptions (document’s correctness, issuer governance, and execution environments) that are not guaranteed by the system. This post summarizes our main findings and, more importantly, the lessons they offer for anyone designing privacy-preserving authorization systems.

What is zkLogin?

zkLogin, as noted, is a prominent instance of a ZKA system, which has been widely adopted across numerous wallets within the Sui ecosystem, and it is used to authorize a substantial volume of real-world transactions: public metrics from Dune Analytics show sustained and

large-scale use of zkLogin-authenticated transactions (see: https://dune.com/queries/6273575). Official information from its designers states that there are over 7.6 million zkLogin transactions and over 500k zkLogin addresses 1. Here, we provide a full view of the zkLogin ecosystem and components. To do this, we carefully analyzed the full system and conduct an analysis of the current live integration: our analysis draws upon the zkLogin academic paper, open-source software, surveys conducted on the official live integration (which we reverse-engineer), official demo, public documentation, Docker Images (via reverse-engineering them) and public security audits.

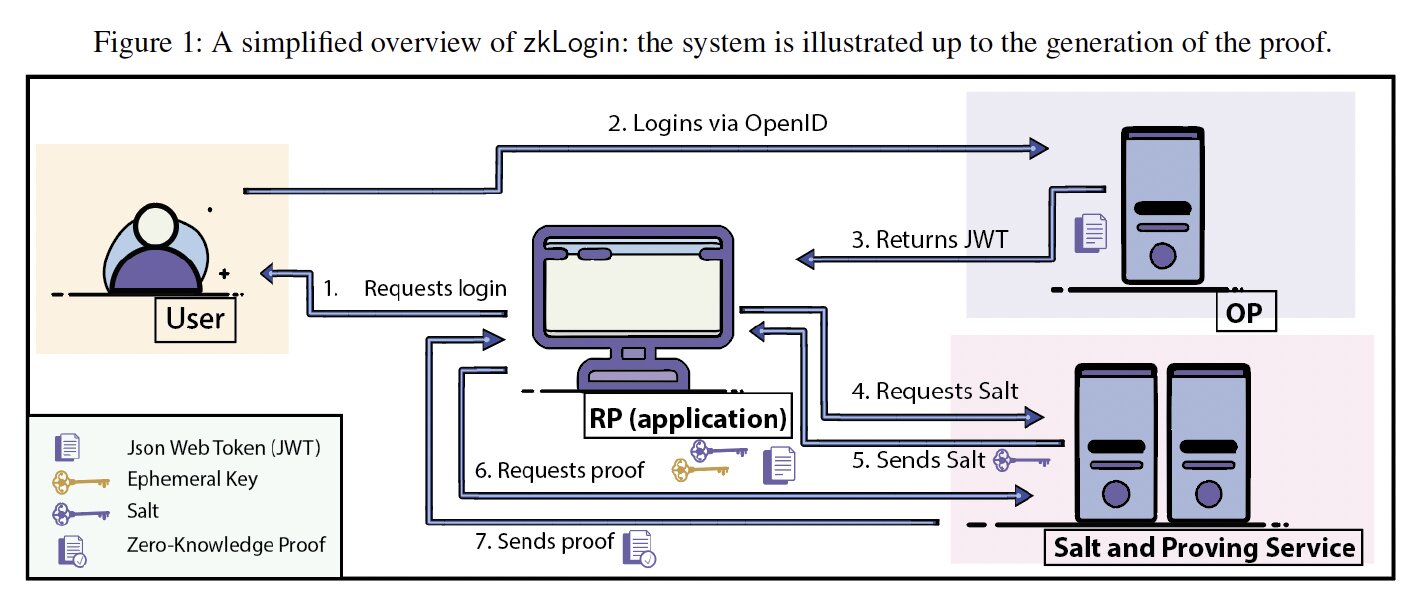

But first, how does zkLogin work?

zkLogin enables users to authorize transactions using a signed JWT issued by an external OIDC Identity Provider (OP). As such, it uses the same parties as OIDC: OP, Relying Party (RP) or the app running on the device, and it expands them with an external proving and salt service. Note that OIDC is a federated-friendly protocol, and, as such, there can be many types of OPs. The core idea of zkLogin is that, instead of maintaining independent application key material, a user proves in ZKP that they possess a valid JWT signed by an issuer (e.g., Google, Twitch, Facebook), and that a fixed subset of the JWT’s claims satisfies a specified predicate. For this, let’s first look at what JWTs are.

JSON Web Tokens (JWTs)

A JSON Web Token (JWT) is a compact, URL-safe token that encodes a set of claims and protects them with a digital signature (or MAC) to ensure integrity and authenticity. A JWT consists of three Base64URL-encoded parts: header.payload.signature, where the header describes the signing algorithm, the payload contains claims (such as the issuer or expiration time), and the signature authenticates both. JWT claims are expressed as JSON key–value pairs. While the signature authenticates the raw bytes of the token, security ultimately depends on how these claims are parsed and interpreted. This includes enforcing semantic checks such as issuer and audience binding, freshness, and intended token use.

A subtle but important issue is key uniqueness. JSON does not mandate how duplicate keys are handled, and real-world parsers differ (“first wins,” “last wins,” or rejection). If different components interpret duplicate keys differently, a signed token may be validated under one interpretation but used under another, leading to serious security vulnerabilities.

JWTs in OpenID Connect (OIDC): In OIDC, RPs must validate JWTs before using them for authentication. This includes verifying the signature and checking security-critical claims like iss (issuer), aud (the RP identifier), sub (the user’s identifier), exp, and iat (for expiration), ensuring they are well-formed, correctly typed, bound to an authentication context, and semantically valid. Verification relies on issuer-provided public keys (via JWK sets), often selected using metadata in the token header such as alg and kid.

Crucially, OIDC validation is stateful and contextual: it depends on external configuration (e.g., client identifiers, issuer metadata), session-binding values (such as nonce and state), and time-varying data like key rotation and token expiration. As a result, JWT security is not just about cryptography: it hinges on consistent parsing, correct semantic enforcement, and careful binding to the surrounding authentication context.

zkLogin flow

zkLogin, hence, works in the federated-friendly setting of OIDC and inherits some of its trust assumptions and those from JWTs. As noted, it introduces two external parties: a proving service and a salt service.

The system assumes that most backend services are untrusted, except for the OP. This mirrors OIDC in spirit: issuers are only trusted through explicit configuration or federation, and a valid JWT merely proves consistency with the issuer, not that the issuer itself is trustworthy. Note that in practice, OIDC provides no global mechanism to exclude malicious issuers, and real-world deployments frequently deviate from the specification. Common issues include missing replay protections, weak audience checks, overly long token lifetimes, and inconsistent claim formats. While traditional RPs can often compensate for these issues with additional checks and session binding, a malicious or attacker-controlled issuer can still generate JWTs that pass basic validation while violating application-level authorization intent, unless a strict issuer allow-list or trust chain is enforced.

zkLogin weakens this boundary by treating the RP as trusted and largely irrelevant to security. As a result, the RP may omit OIDC validation entirely and forward malformed or weakly validated JWTs to the proving and salt services. These services occupy an ambiguous trust position: they may be operated by the RP or by third parties with no direct relationship to the issuer and little context about RP policy. In such settings, JWTs are often accepted largely at face value, shifting responsibility for correct validation without providing any issuer-authoritative enforcement mechanism.

The flows of the protocol are: registration, request and issuance of JWT, (potentially external) salt-generation, (potentially external) proof-generation and verification. Let’s look at them now.

Registration: Before using zkLogin, a RP, such as a wallet or application, must first register with an OP. Through this process, the OP assigns the RP a public identifier, client_id, which the OP later embeds into the audience (aud) claim of issued JWTs. After OIDC registration, the RP separately registers its client_id with the zkLogin proving service and, optionally, salt service. These external backend services maintain their own issuer allowlists and mappings from issuers to public key registries (e.g., JWKS endpoints).

Login and Issuance of JWT: Prior to initiating the OIDC login flow, the RP locally generates zkLogin-specific authorization material: an ephemeral key pair (vk_U, sk_U), a random value r, and a maximum validity bound T_max defining the intended lifetime of the authorization epoch (which is longer than a OIDC login session). These values are combined into a nonce nonce=H(vk_U ∥ T_max ∥ r), which is embedded into the OIDC authentication request. The user then authenticates with the OP via a standard OIDC flow, after which the issuer returns a signed JWT containing claims such as issuer (iss), subject (sub), audience (aud), and the supplied nonce. While the JWT itself is short-lived and scoped under OIDC semantics, note that zkLogin decouples authorization from authentication as the the tuple (vk_U, sk_U, r, T_max) persists beyond the JWT’s expiration (often determined by the exp claim of the JWT), effectively establishing an authorization epoch that may outlive the underlying login session. Further, it is expected that several OIDCs logins will render the same JWT, so that it can be reused. Moreover, zkLogin repurposes the OIDC nonce from a OIDC-session-level replay-prevention mechanism into an epoch-level unlinkability primitive, and does not require it to be validated against stored session state.

Preparing for Proof Generation: After a successful login, the JWT is returned to the RP rather than being sent directly to the external proving service. The application may either persist the JWT locally (allowing easy reuse), or immediately forward it for proof generation. Although OIDC mandates extensive JWT validation (covering signature verification, JWT’s claim well-formedness, issuer and audience binding, and temporal validity), zkLogin documentation recommends only verifying the signature at this level. To mitigate address linkability across applications, zkLogin introduces a user-specific salt and derives the on-chain address as zkaddr=H(sub ∥ aud ∥ iss ∥ salt). The salt used for this may be generated locally or retrieved from an external salt service, often by forwarding the JWT itself. The salt is then stored client-side, frequently in browser local storage, and may be reused indefinitely; its secrecy and persistence become critical for privacy, yet it is not cryptographically bound to a device, application, or session.

Proof Generation: To authorize actions, the RP requests a zero-knowledge proof (π), typically by outsourcing proof generation to an external proving service maintained by a third party (the proving server): this is done by using a ZKP circuit in an externally-operated machine 2.

In order to do so, the client forwards the JWT, salt, (vk_U, T_max, r), and derived address (zkaddr) to the prover, often via a standard HTTPS request in which the JWT is handled as explicit application data rather than a protected browser credential. The proving service performs a minimal audience check against a registered client_id, and then executes the zkLogin circuit. Rather than fully parsing and validating the JWT as JSON, the circuit uses “ad-hoc selective parsing”: it locates one instance of a fixed claim substrings (iss, aud, sub, nonce) via positional string searches, checks only for surrounding quotation marks and delimiters, and ignores canonicalization, unique-key enforcement, typing, and full JSON validity. The resulting proof attests that (i) the JWT satisfies this ad-hoc parsing procedure, (ii) its signature verifies under a trusted issuer key, (iii) the nonce corresponds to H(vk_U ∥ T_max ∥ r), and (iv) the claimed address was derived correctly using the salt. Neither the prover nor the verifier maintains state about nonce or salt reuse, nor do they check whether the epoch parameters remain consistent with the original JWT context.

Verification and Executing Actions: To execute a transaction, the user signs the payload using the ephemeral private key sk_U (creating the signature σ_U) and submits the tuple (vk_U, T_max, σ_U, π, JWT header, iss) to the verifier. The verifier first checks that the issuer’s public key is recognized as valid (typically via periodically fetched JWKS data), then enforces that the epoch parameter T_max lies within an acceptable window relative to the current epoch. Finally, it verifies the ZKP (π), which attests to the correctness of the ad-hoc selective claim extraction/parsing, signature verification, nonce construction, address derivation, and the action signature under vk_U. If all checks succeed, the transaction is authorized.

By doing this flow, zkLogin has effectively transformed a short-lived session-bound web authentication artifact into a reusable authorization credential whose validity is governed by epoch parameters and local state, rather than by the original OIDC session semantics.

Vulnerabilities: When Authorization Inherits the Messiness of the Web

The usual security story for zkLogin goes like this: if the verifier accepts a proof that a JWT was validly signed by an OP and contained the right claims via the ad-hoc selective parsing procedure, then authorization must be secure. This story, however, can be wrong. What the verifier actually accepts is a proof about how one component chose to interpret a raw byte string, under a particular parsing non-standarised heuristic, issuer allowlist, and execution context. These choices are not fixed by the protocol, not visible to the verifier (or other parties), and in several cases are explicitly pushed onto untrusted infrastructure.

Because zkLogin does not provide a full threat model beyond trust assumptions of parties, we consider three adversarial settings when we looked at this protocol:

-

Standard (network) adversary, able to intercept and modify communications between the RP, external services, and the issuer.

-

Malicious-services adversary, controlling the prover, salt service, and/or issuer infrastructure.

-

Compromised-RP adversary, temporarily compromising the user device running the RP (e.g., via a malicious browser extension).

For the vulnerabilities found, we consider a conservative threat model in which the proving and salt services are untrusted but semi-honest: they follow their published interfaces and do not actively collude with attackers or generate malformed proofs, but may deviate in policy enforcement or validation strictness. This assumption is weaker than the zkLogin paper’s adversarial model, which treats backend services as fully malicious. Importantly, the vulnerabilities we describe do not rely on active misbehavior by these services; they arise from missing or underspecified binding and validation checks and therefore apply a fortiori when the services are fully malicious.

For the remaining parties, we adopt stronger adversarial assumptions. We treat the OP under the malicious-services model: the OP may be attacker-controlled or misconfigured and may issue syntactically valid and correctly signed JWTs that violate intended semantic constraints. This is not an unrealistic constraint as it has been shown that OPs can issue malformed JWT: Unit 42, for example, reports critical OIDC misconfiguration patterns in CI/CD ecosystems affecting major vendors such as CircleCI and GitHub Actions. We also consider the RP under a compromised-RP model: the RP environment may be affected by injected scripts, malicious browser extensions, compromised dependencies, or brief device compromise. In such cases, the RP may forward malformed or semantically invalid JWTs to external services and store long-lived authorization material in browser-accessible memory or storage. This directly contradicts a key trust assumption made by zkLogin, which treats the front-end application as trusted and required only for liveness, not security, by arguing that front-end code is public and thus “subject to greater public scrutiny” 3. In browser-based deployments, however, trust cannot be inferred from source-code visibility alone. Runtime compromise of the client environment enables extraction and replay of sensitive bearer artifacts, an attack surface well established in prior work.

We argue that this threat model is realistic. OPs operate outside the system’s administrative boundary; zkLogin explicitly supports outsourced proving and salt services; and many deployments rely on browser-based RPs with limited isolation guarantees. A secure zkLogin design should therefore remain robust in the presence of third-party services, heterogeneous issuers, and partially compromised RP environments that do not share a single trust domain.

Here, we describe three broad classes of vulnerabilities that arise from zkLogin’s design choice. None of them involve breaking cryptography or zero-knowledge proofs. Instead, they stem from semantic ambiguity, missing binding guarantees, and architectural trust shifts. Together, they show that zkLogin’s security does not reduce only to the ZKP.

1. The Parser Is the Protocol

At the core of zkLogin lies a subtle but critical design choice: the system does not prove statements about JWTs as defined by OIDC or the JWT standard. Instead, it proves statements about how a particular circuit parses a byte string that is claimed to be a JWT. This distinction is not cosmetic. It fundamentally reshapes what security guarantees the system can (and cannot) provide.

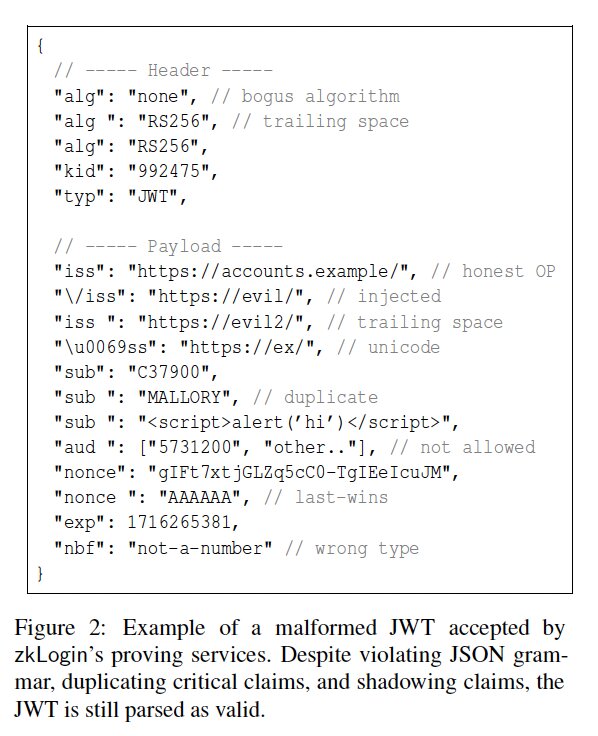

In zkLogin, the zero-knowledge circuit responsible for “verifying” JWT claims does not implement a standards-compliant JSON parser. It does not enforce JSON validity, canonical encoding, unique keys, or correct typing. Instead, it performs ad-hoc selective parsing: it searches for one instance of fixed substrings corresponding to a small set of expected claims (iss, sub, aud, and nonce), checks for superficial syntactic markers such as quotation marks and delimiters, and extracts whatever lies between them. Everything else in the payload is ignored.

As a result, zkLogin never establishes that the JWT payload is a well-formed JSON object, let alone that it has a unique or unambiguous interpretation. The proof attests only that there exists a way to extract certain substrings from the signed byte string that satisfy the circuit’s local checks. This immediately creates a class of semantic confusion vulnerabilities (some of them are highlighted in the Figure below).

Claim ambiguity and shadowing: From a practical perspective, JSON allows for duplicate keys, while leaving their semantics undefined, even though the JWT RFC asks for unique claim’s name. Real-world parsers disagree: some reject claims that are duplicated, others implement “first wins” or “last wins” behavior. zkLogin does not reject duplicate keys, nor does it specify which occurrence is authoritative. This means a single signed JWT payload can contain multiple iss, sub, aud, or nonce fields, with different values. The circuit may extract one occurrence, while other components (wallet code, logs, UI, backend services, or even the issuer’s own libraries) may interpret another. Because the verifier never sees the payload, it has no way to detect or resolve these inconsistencies. In effect, zkLogin allows claim shadowing: an attacker-controlled issuer (or a misconfigured one) can embed benign-looking claims early in the payload and override them later, while still producing a proof that passes verification. The ZKP is sound, but the meaning of the statement it proves is ambiguous.

Non-canonical encodings and parser differentials: The circuit’s parsing logic tolerates arbitrary characters inside quoted strings. It does not validate escape sequences, Unicode normalization, control characters, or embedded quotation marks. This enables parser differentials across the system: different components may interpret the same claim string differently depending on their JSON libraries, string handling rules, or sanitization practices.

This is not a purely theoretical concern. JWT claims are frequently logged, embedded into URLs, or forwarded to other services. Allowing attacker-controlled, non-canonical strings to be bound into authorization proofs expands the attack surface well beyond the authorization check itself. In a traditional OIDC flow, such issues are mitigated by short token lifetimes and strict validation at the RP-level. In zkLogin, the same malformed payload can be reused to mint long-lived authorization proofs.

Proving bytes, not meaning: The deeper issue is structural: zkLogin never fixes the semantics of the object it reasons about. There is no canonical grammar for JWT parsing specified at the protocol level, uniqueness of claims, and no guarantee that all parties interpret the payload in the same way. The ZKP therefore attests to compliance with one particular parsing strategy, chosen by the prover and embedded in the circuit, rather than to a universally agreed-upon interpretation of a JWT.

This means that correctness depends on unstated assumptions: that issuers never produce malformed or ambiguous JSON, that all components agree on parsing behavior, and that ad-hoc substring extraction is “close enough” to real JWT validation. These assumptions routinely fail in real-world identity systems.

The lesson here is not that ZKPs are weak, but that they faithfully amplify whatever semantics you give them. If the input object is ill-defined, the proof will be too. In zkLogin, non-canonical JWT parsing turns authorization into a proof about strings, not about identities or authentication events, and the difference matters.

Acknowledged, but Underexplored, by zkLogin: The zkLogin paper itself acknowledges that allowing escape sequences in JSON keys can break security: if keys contain escaped quotes, claim binding may fail. This confirms that key canonicalization and unique-key enforcement are security-critical, not just interoperability concerns. However, the paper treats escaped quotes as an isolated edge case and does not address the broader class of non-canonical encodings and character smuggling in claim keys and values. More importantly, it overlooks the downstream risk of tainted claims: even with a valid JWT signature, attacker-controlled strings may propagate through the system and affect later components.

Preventing claim confusion therefore requires more than blocking a single pattern. It demands strict, canonical parsing and sanitization throughout the entire zkLogin pipeline, from JWT ingestion to proof generation and consumption.

2. From authentication to authorization, without binding

In practice, zkLogin’s security relies on several environmental assumptions that are not enforced by the protocol itself: (i) provers correctly enforce a strict issuer allow-list; (ii) the aud claim reliably identifies and authorizes the RP, despite being public and not cryptographically bound to the RP; and (iii) JWTs admit a unique, canonical interpretation under the prover’s implicit parsing model. We show that each assumption can be violated in realistic deployments, enabling unauthorized proof generation and ultimately cross-RP and cross-subject impersonation. For this, let’s look at malicious issuers, unauthorised access to salt and proving services, and the storage of zkLogin’s material.

On Malicious issuers: The zkLogin reference implementation expands issuer trust beyond an explicit allow-list by accepting any Amazon Cognito user pool whose iss matches a fixed URL pattern. Concretely, any issuer string of the form https://cognito-idp.<region>.amazonaws.com/<tenant_id> is treated as trusted, with verification keys dynamically fetched based on attacker-controlled values embedded in iss. This allows any adversary to instantiate a malicious Cognito issuer that is accepted by default.

While some hosted provers enforce additional issuer restrictions, this is a deployment-specific mitigation rather than a protocol guarantee. Issuer trust is treated as mutable prover configuration rather than a first-class security parameter bound into verification semantics and for the whole protocol. In federated OIDC settings (where attacker-controlled issuers are feasible) this assumption is particularly fragile. Unlike WebPKI, where trust roots are explicit, audited, and ecosystem-wide, zkLogin leaves issuer trust policy underspecified and unenforced at the protocol level.

On unauthorized prover and salt service access: Access to proving and salt services is commonly gated by RP-specific API keys. In observed deployments, these keys are transmitted directly from browser environments and stored directly in client-accessible state at the browser level. Because the API key uniquely identifies an RP, its disclosure enables direct RP impersonation when invoking external services.

Critically, this API key is a static bearer credential and is not cryptographically bound to protocol values such as aud, iss, or the JWT being proven. As a result, possession of the key suffices to request proofs for arbitrary JWTs, including those whose aud does not correspond to the RP that registered the key. Even maintaining an allow-list of acceptable aud values per RP only enforces set membership, not binding to the specific authorization context under which the JWT was issued. Consequently, the proving service effectively becomes a generic proof oracle: any party holding an RP’s API key can generate proofs for identities and applications unrelated to that RP, while presenting those proofs as originating from a legitimate zkLogin flow.

The missing binding extends to the subject identifier sub. In OIDC, sub is defined only relative to a particular issuer and issuance context; it has no global meaning independent of iss. zkLogin does not enforce any binding between sub, iss, and the RP identity requesting the proof. Since sub values are issuer-defined and unbounded, they cannot feasibly be pre-registered or allow-listed by the prover.

As a result, an RP (or attacker) holding an API key can request proofs for arbitrary subjects or RPs, without demonstrating control over the corresponding JWT, an active session at the issuer, or consistency with the intended authorization context. Nothing at the proving interface enforces that the subject attested in the proof corresponds to the authenticated RP identity.

A correct design would authorize proof generation only for consistent tuples (iss, sub, aud, RP), and ensure that this binding is explicitly attested in the ZKP. zkLogin provides neither protocol-level mechanisms nor implementation guidance to enforce such constraints.

On browser trust assumptions: zkLogin deployments frequently store (and encourage to do so) long-lived authorization material (including API keys, salts, and cryptographic state) in insecure browser-accessible storage (local storage or session storage) and transmit these values directly from client-side code to external services. This contradicts OAuth and OIDC best practices, which explicitly discourage placing bearer credentials in browser contexts.

Browser isolation mechanisms (SOP, CSP) do not provide the confidentiality or integrity guarantees assumed by zkLogin even though the documentation notes that “the same-origin policy for the proof prevents the JWT obtained for a malicious application from being used for zkLogin”. All same-origin scripts (including third-party libraries and injected dependencies) have full access to origin storage and network capabilities. Origin isolation constrains where requests originate, not who they authenticate as. Static bearer credentials trivially bypass these protections.

Thus, reliance on browser trust assumptions amplifies impersonation risk: stolen API keys and salts can be reused from any context to generate new proofs, independently of the original JWT or application.

End-to-end attack

Combining these issues yields an end-to-end cross-impersonation attack without breaking cryptography or deviating from documented behavior. An attacker can:

-

Register a malicious AWS Cognito issuer accepted by pattern matching.

-

Extract an RP’s API key from a browser-based integration.

-

Construct a JWT containing a chosen

audand attacker-selectedsubunder the malicious issuer. -

Submit the JWT to the proving service using the stolen API key.

The result is a valid zkLogin proof attesting to an identity and RP context unrelated to the legitimate authorization flow. The vulnerability arises entirely from missing bindings between RP identity, issuer trust, subject identity, and proof authorization, not from cryptographic flaws.

More broadly, these issues are exacerbated by treating JWT-derived proofs as reusable authorization credentials that can be safely stored at the browser insecure storage. JWTs were designed as short-lived authentication artifacts: using them (or their ZK derivatives) for long-term authorization, especially when stored client-side, magnifies replay and impersonation risks.

3. Centralization and Privacy Risks

Despite its stated goals of decentralized and privacy-preserving authentication, zkLogin recentralizes trust around a small set of actors: a fixed group of identity issuers, outsourced proving and salt services, and browser-based clients that store long-lived bearer artifacts. Even in federated OIDC environments, zkLogin remains structurally centralized: proof validity ultimately depends on issuers maintaining stable namespaces, subject semantics, and public keys, while proving and salt services maintain global state such as issuer-to-key mappings, JWT storage, and allow-lists.

zkLogin also centralizes identity around issuer-managed user accounts. Participation requires users to hold accounts at specific platforms, embedding existing web identity providers directly into the authorization layer rather than removing reliance on them. Because each authentication flow is issuer-mediated, the issuer can observe which RP a user logs into via aud, redirect metadata, and related context, a known privacy limitation of federated SSO. Moreover, issuer identifiers are exposed to system participants, facilitating cross-RP linkability when combined with other forwarded material.

Forwarding JWTs to external proving or salt services further expands the trust boundary. JWTs frequently embed sensitive attributes (e.g., email addresses, profile information), which are disclosed to third-party services (salt or prover) that were not part of the user’s original OIDC consent decision. The consent granted during authentication authorizes disclosure to the RP, not to an external prover operated by a separate entity. zkLogin provides no mechanism to inform users of this secondary disclosure, rendering the original consent semantically incomplete.

Token handling at these external services is opaque. The documentation offers no guarantees about JWT retention, inspection, aggregation, or the linkability of derived salts or keys across applications. Users are not informed whether identifiers persist at centralized proving services serving multiple wallets and RPs, nor whether repeated uses can be correlated. Public documentation contains little explicit analysis of these privacy and linkability risks.

Finally, zkLogin does not clearly directly improve usability or user autonomy when compared to maintaining private key material. Correct operation still depends on long-lived secrets: salts must be persistently stored; RP API keys must be protected indefinitely; and ephemeral cryptographic material must remain recoverable. Rather than eliminating secret management, zkLogin largely shifts it from explicit cryptographic wallets to opaque client-side storage and static bearer credentials, with corresponding security and privacy trade-offs.

Ethical Considerations and Responsible Disclosure

We conducted this research under a responsible disclosure process. All findings were shared with the zkLogin designers and Sui in November 2025, with follow-up communication in February 2026. Our disclosure included a detailed technical report covering architectural, parsing, policy, and centralization vulnerabilities, together with concrete remediation recommendations.

In particular, we recommended: (i) enforcing specification-compliant JWT parsing and validation at the RP; (ii) strict issuer allow-listing without pattern-based trust (e.g., AWS Cognito templates); (iii) cryptographic binding between issuer, subject, audience, and RP identity (e.g., API key); (iv) prohibiting storage of long-lived authorization material in browser-accessible environments; (v) eliminating exposure of RP API keys to the browser; (vi) stricter validation at proving and salt services, including canonical JSON and key-uniqueness enforcement; and (vii) explicit user consent before forwarding sensitive JWTs to third-party proving services.

The response we received addressed only client-side key exposure, asserting that TLS and JWT scoping provide sufficient protection. Our analysis shows this to be incorrect: API keys are bearer credentials whose possession alone enables misuse across contexts; TLS does not protect against runtime compromise of the browser environment; and static browser-exposed credentials prevent targeted revocation and incident containment. Established web security patterns (short-lived credentials, proof-of-possession bindings, backend-mediated invocation, or OAuth Authorization Code Flow with PKCE) would significantly reduce these risks.

At no point did we exploit these issues in production systems or interact with real user data. All experiments were conducted using test accounts, locally generated JWTs, and public testnet endpoints. Reverse engineering was limited to publicly distributed artifacts intended for third-party deployment and was performed solely to understand undocumented security-relevant behavior. We avoided generating impersonation-capable credentials and followed standard ethical guidelines for security research throughout.

What This Means for ZK Authorization Systems

What we found, as part of this analysis, is not a failure of ZKPs, but it is a lesson in systems security. If you build ZK authorization on top of real-world authentication ecosystems, you must treat the following as first-class security properties:

-

canonical parsing and unambiguous semantics,

-

issuer trust and governance ingrained in the protocol,

-

binding between authentication context and authorization,

-

lifecycle management of credentials,

-

deployment and storage assumptions.

Our analysis shows that _zkLogin’_s core security assumptions do not hold under realistic adversarial conditions. The vulnerabilities we identify undermine the guarantees zkLogin claims to provide, including issuer-bound authorization, input integrity, unlinkability, and decentralization. These are not isolated implementation bugs, but consequences of architectural design choices that repurpose short-lived web authentication tokens into long-lived authorization credentials.

A recurring theme is composition failure. Parsing ambiguities allow adversarially shaped JWTs; the absence of RP-side validation enables malformed tokens and audience confusion; external proving and salt services amplify trust without enforcing issuer–RP–subject binding; and browser-based storage of cryptographic material turns logical flaws into practical exploits. Each layer weakens the system in isolation; together, they negate its intended security model.

The weaknesses span the entire pipeline. At the identity layer, issuer, audience, and subject bindings are not enforced with correct temporal or semantic constraints. At the proving layer, circuits validate only narrow byte-level properties while assuming parsing semantics incompatible with JSON and OIDC. At the blockchain layer, validators rely on incomplete or stale issuer metadata, with no mechanism to ensure that proofs correspond to the RP or authorization context under which the JWT was issued.

More broadly, zkLogin illustrates a deeper problem with extending web authentication artifacts into cryptographic authorization systems without a unified threat model. The design combines OIDC semantics, ad hoc parsing logic, outsourced proving services, and blockchain-specific expiry rules without a principled end-to-end security framework. As in other federated identity systems, this leads to brittle trust boundaries, opaque data flows, and trust relationships that outlive the tokens from which they derive.

These risks are magnified when such systems are proposed for high-stakes identity settings, such as digital identity wallets or government-backed attestations. Repurposing web tokens while weakening issuer, audience, and consent guarantees risks entrenching centralized identity providers as long-term authorization oracles, exposing sensitive personal data to third-party provers, and eliminating meaningful revocation and policy control. Systems of this kind should not be deployed without rigorous, formal security and privacy analysis, and without reconsidering whether session-bound web authentication tokens are an appropriate foundation for cryptographic authorization at all.

To read our full report, check the full paper at: https://eprint.iacr.org/2026/227