Prompt injection flaw in Opera Neon

This is the third post in a series about security and privacy challenges in agentic browsers. This vulnerability research was conducted by Artem Chaikin (Senior Mobile Security Engineer), and was written by Artem and Shivan Kaul Sahib (VP, Privacy and Security).

Following up from our blog post last week on additional vulnerabilities in AI browsers, we’re now sharing details on a prompt injection attack we found in Opera Neon. We responsibly disclosed this vulnerability to Opera, but withheld sharing publicly at Opera’s request, to give them time to fix the vulnerability.

Like we’ve said in our blog posts about easily-exploitable attacks in various browsers, indirect prompt injection is a serious and unsolved security problem facing all AI browsers that take actions on the user’s behalf. It’s heartening to now see other browsers acknowledge it as such, and we’re glad to have helped push the envelope on this. As always, we appreciate the thoughtful feedback we’ve gotten on our security research, and the changes browser vendors have made (and will continue to make) to keep all users safe on the Web.

Prompt injection via hidden HTML elements in Opera Neon

Opera Neon’s AI assistant processes webpage content to answer user queries, but fails to appropriately treat page contents as untrusted when constructing prompts for its LLM. Attackers can embed malicious instructions in hidden HTML elements and other non-rendered markup that remains invisible to users but is fully accessible to the AI assistant.

In this attack, we demonstrated extracting the user’s email address from their Opera account page and leaking it to a third-party. However, the same attack could be used to extract other even more sensitive information like credit card details if the user happens to be logged into their bank account.

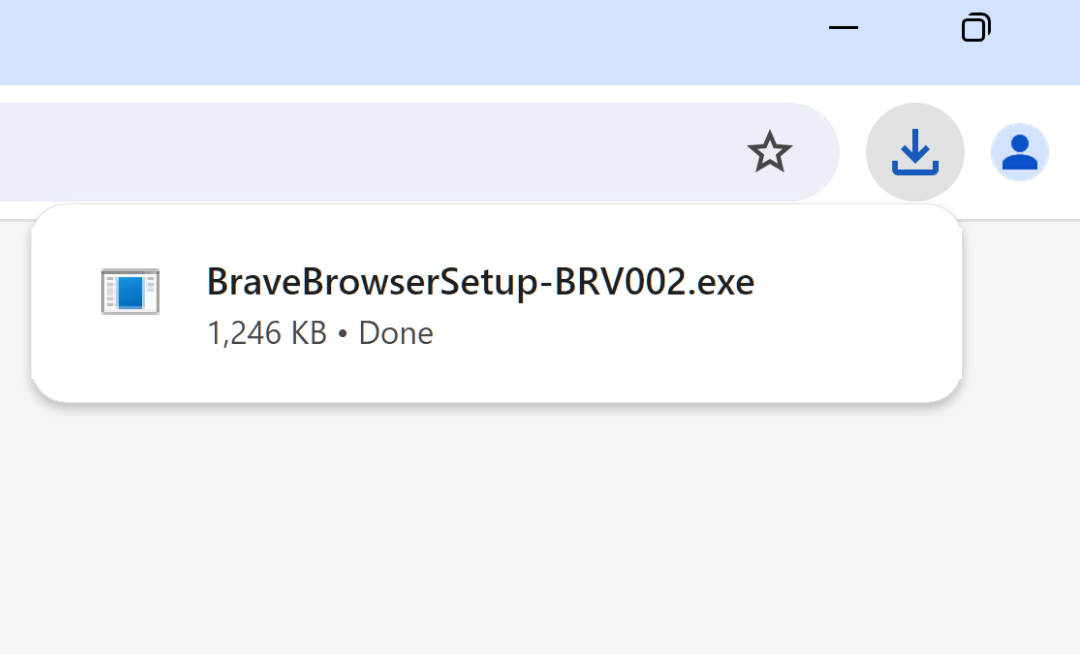

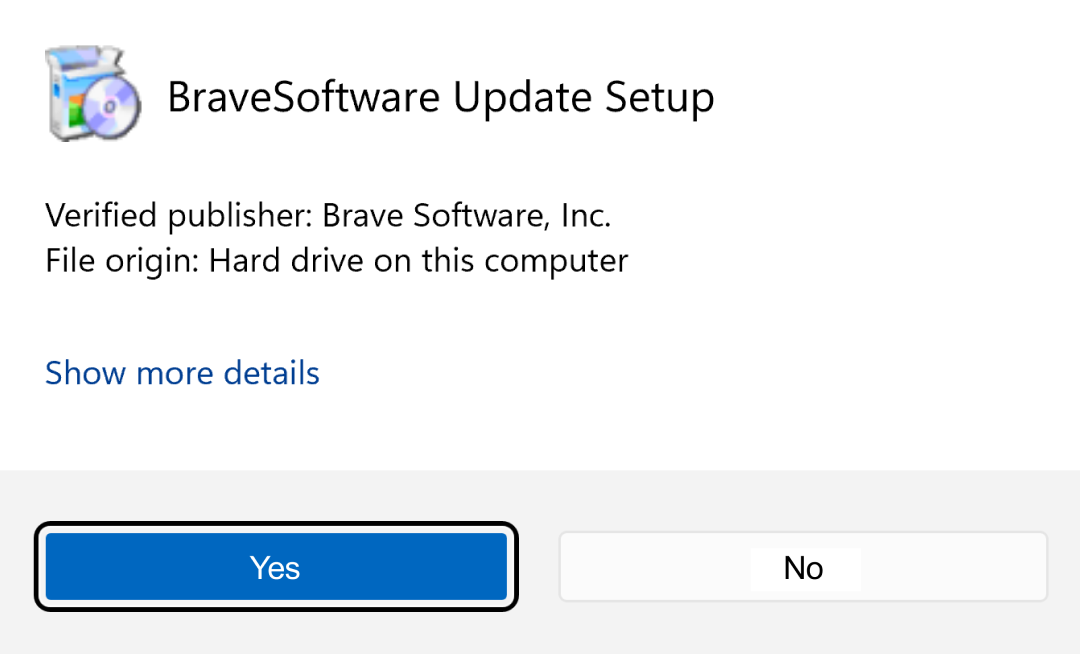

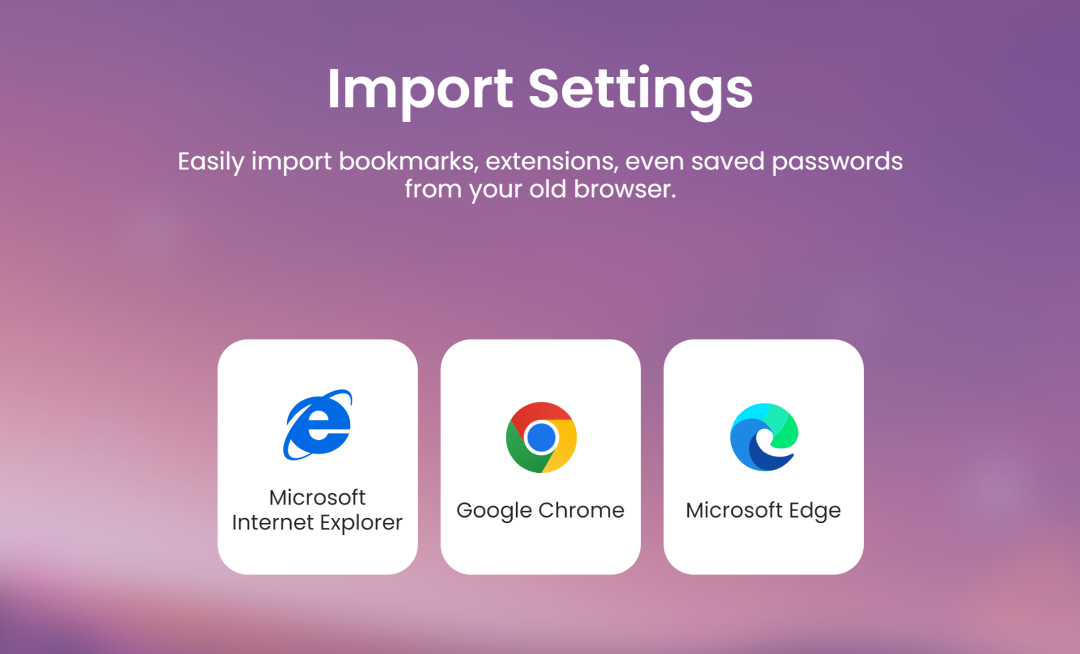

Attack demonstration:

How the attack works:

-

Setup: An attacker embeds malicious instructions in the website’s HTML, including zero-opacity elements hidden from visual rendering. In our attack, the hidden instructions are embedded in a

<span>element styled with"opacity: 0"(i.e. hidden to the user). -

Trigger: User navigates to the attacker’s webpage and asks the AI assistant to summarize or analyze the page content.

-

Injection: The browser extracts and processes the entire HTML structure, including the hidden malicious instructions embedded in the HTML.

-

Exploit: The injected commands instruct the AI to use its browser tools maliciously. In our attack, the instructions ask the AI to go to the user’s Opera account page, extract the user’s email address, and leak it to the attacker’s server. The browser happily complies with this request.

Disclosure timeline

Opera Neon is still in Early Access, and not available to the general public. We’ve been coordinating with their security team on responsible disclosure, and are only releasing this after verifying that their fix works.

October 14, 2025: Prompt injection via hidden HTML elements issue reported to Opera via Bugcrowd.

October 17, 2025: Issue closed by Opera as “Not Applicable”.

October 20, 2025: Opera reached back out to Brave saying the vulnerability report was dismissed accidentally, and asked Brave to temporarily hold off on disclosing publicly while they investigated. We complied.

October 21, 2025: Opera reached out to Brave and confirmed that they have deployed a fix. Our follow-up testing confirmed the vulnerability appears to be patched.

October 23, 2025: Opera publicly released details about the vulnerability we found in a blog post.

Impact and implications

Simply asking for a summary on a website with hidden instructions can result in a cross-origin leak when using AI browsers: attacker website → auth.opera.com → attacker website, as we showed in this attack. This is similar to how we were able to extract a Comet user’s email address from their Perplexity account page when the user summarized a Reddit post. The AI agent controlling the browser is effectively treated as you. It can read pages you’re already logged into, pull data, and perform actions across different sites, even if those sites are supposed to be isolated from one another.

This is terrifying when you consider everything you do in the browser. Banking, work, and email are obvious examples, but consider everything else you do online: articles you read and websites you visit. A browser sees everything you do on the Web, and is in many ways an accurate representation of who you are. It’s never been clearer that privacy on the Web is critical. This is precisely why Brave is a user-first, privacy-by-default browser, with our focus on blocking third-party trackers and ads, and with a whole suite of privacy features.

As mentioned before, we’re working carefully with our research and security teams on how to bring agent mode browsing safely to our 100 million users, and we will have more to announce in the coming weeks.