Web3 is the decentralized Web. It’s built on cutting edge technology like blockchain and crypto, but at root Web3 is a movement towards a more equitable Internet. It gives users control of their data, rather than Big Tech.

But before we dive into all that, let’s take a look at the history of the Internet—because the best way to understand Web3 is to learn about what came before it.

Note: The division between the various “versions” of the Web are more descriptive than technical. The Internet has worked roughly the exact same way for decades; we’ve just come up with new ways of building on it and interacting with it. Today, a developer could build a website using Web 1.0, 2.0, or Web3 standards. A new version doesn’t mean the old way of doing things disappears. It just means a new set of Web standards became more popular and common.

Web 1.0: the read-only Web

Web 1.0 was the earliest version of the Internet that everyday people could actually use. It started around 1989, in the days of dial-up connections and clunky desktop computers. At the time it was known as the “World Wide Web.”

Web 1.0 spanned the early days of the Internet, roughly through 2005. It was marked by static content (rather than dynamic HTML), with data and content served from a static file (rather than a database). In Web 1.0, websites didn’t have much interactivity. You could read things that other people published, but that was about it. Basically it was like digital magazines and newspapers, only with comment threads turned off. There wasn’t much social media and—other than very early blogs—people couldn’t create or post their own content.

Due to this lack of interactivity, Web 1.0 is known as the “read-only” Web.

The first use cases and websites on Web 1.0

The main use case of the early Web was sharing (mostly scientific) data between different research organizations spread across the world. The first proper website in existence belonged to the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN), and many that followed belonged to universities and research institutes. The early Web was essentially one big network for scientists and researchers.

By mid-1993, the Web consisted of just barely over one hundred websites. Then things grew fast. By the end of 1993, there were 600+ websites. By the end of 1994, over 10,000. This surge meant people other than scientists and researchers were using the Web.

Looking at the emergence of some of the earliest websites, you’ll notice some familiar Big Tech companies, and some services you still might use today. You’ll also notice…Pizza Hut? Yes, really. Some of the first big Web 1.0 sites to launch were:

- Apple (earliest site launched in 1993)

- IMDb (1993)

- Amazon (1994)

- IBM (1994)

- Microsoft (1994)

- Pizza Hut (1994)

- Yahoo! (1994)

- Craigslist (1995)

- eBay (1995)

- Ask Jeeves (1996)

- BBC (1997)

- Google (1997)

By 1996, the Web had over 200,000 websites, and the dot-com boom was well underway. Still, by today’s standards the Web was primitive. Most websites served info to users who wanted to read it—and that was about it. The transition from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0 took place over many years as the infrastructure and development tools of the Internet became more advanced—and as more people began to participate.

Web 2.0: the social Web

By the late 90s, the transition to Web 2.0 had begun (although the features that characterize Web 2.0 weren’t widespread until around 2004).

The transition started when some Web 1.0 sites introduced “social” features. eBay, for example, opened their pages to testimonials and comments, and gave users the ability to “rate” buyers and sellers.

Web 2.0 is the Internet most of us know today. It’s social media, instant website creation, portfolio sites, blogs, and forums…basically any platform where you can easily upload content and make it visible to others. It’s also the Web of apps, for everything from banking to grocery orders to ridesharing. Facebook, YouTube, Wikipedia, Amazon, Yelp!…almost any site you can post to, publish from, or log into is considered Web 2.0. They use dynamic HTML, and the content is often served from a database.

For about the first decade of the Internet, users could connect and read content—maybe even order a pizza or bid for an item on eBay—but not much more than that. Web 2.0 gained popularity because it marked the first time that users could create content themselves.

For this reason, Web 2.0 is sometimes called the “read-write” Web, or the “social” Web.

The downsides of Web 2.0: too much centralization and not enough privacy

While Web 2.0 democratized publishing, Big Tech companies were busy making the Web a dictatorship. They control the infrastructure, the apps, and the servers, so they decide who can play, when, and how. And in exchange for “letting” you participate, they make you give free access to your data, which they then sell to the highest bidder (getting disgustingly rich in the process).

To put it simply, Web 2.0 has two core problems: a total lack of data privacy, and far too much centralization.

Disappearing privacy: how tech companies profit from user data

Web 2.0 apps are often “free,” in that there’s no charge to use the service. But the companies behind these apps have to make money somehow. So instead they “monetize” their users: They collect mountains of personal data, and profit off it in the form of highly targeted ad space they sell to online advertisers.

Consider the example of online shopping. In Web 2.0, if you shop for a pair of shoes online, you’ll be followed by disturbingly accurate ads for those same shoes on other websites, in your newsfeed, or even your email inbox.

That’s because your online behavior (like searches, clicks, and purchases) often gets recorded by the sites and apps you use thanks to cookies, trackers, and other creepy tools. Even creating an account on many sites and apps requires users to hand over sensitive personal info. Then the data is often sold and shared. The data collection that powers this following (or “retargeting”) has led to massive data leaks, where Big Tech gets hacked for millions of user passwords, credit cards, or social security numbers.

The challenge with Web 2.0 is that users often have no control over whether their data gets collected, how it’s stored, or what Big Tech does with it. Basically, you trade your data to use the app. Since tech companies aren’t making money directly from their products, you become the product.

The centralized authority problem

The other major downside of Web 2.0 is that it relies on centralized authority. Think governments, Big Tech, and Big Banks. These central authorities verify your identity, authorize online transactions, control who can publish content (and what kind of content), and more. Essentially, Web 2.0 companies act like a benevolent dictatorship: They decide who’s allowed in or out, and what they can do.

Consider the example of online banking. Whatever bank you use holds your assets. They decide how you access them (e.g. with debit cards, ATMs, or mobile apps). They say who you can transact with. And, most importantly, they validate your identity and access (based on info from other centralized authorities like a government, as with social security numbers, passports, or ID cards).

And this is just one example. Behind the scenes, Big Tech is used to validate your identity and grant you access to thousands of services. Most people have no idea how often Facebook and Google are used as authentication services for other apps.

In Web 2.0, the individual has very few individual rights. Things like Europe’s GDPR and California’s CCPA do grant users more rights to disclose what’s collected, how, where it’s stored, and how it’s destroyed. But in the end, the core problem persists: centralized authority.

Understanding Web3: the decentralized Web

Web3 takes the “social” model of Web 2.0 and alters its underlying structure to make it more fair, public, and decentralized. It’s simply a new kind of infrastructure, a new way of building the things you’re already used to. Web3 still has things like social media, video streaming, and finance apps. It’s just that those “DApps” are now decentralized.

Learn more about DApps and what’s being built on Web3.

The technology that makes Web3 possible

Web3 relies on cutting edge technologies like blockchain and cryptocurrency. In fact, the idea of a decentralized Web was born from the first successful blockchain networks and cryptocurrencies. This is the underlying tech that makes it possible to decentralize the Web.

Take a look at the foundational technologies of Web3 and how it’s all made possible.

The origin and development of Web3

The Bitcoin network launched in 2009, marking the first time an emerging, decentralized technology challenged a centralized authority (i.e. Big Banks and fiat currency). Bitcoin’s primary purpose is to serve as digital money: a way to exchange value, digitally, without needing to trust a bank. It was a novel and revolutionary concept. And although rudimentary by today’s standards (since all it really does is enable transactions), Bitcoin was the first successful blockchain network, and the technological force needed to start decentralizing all kinds of old systems.

In 2015, the Ethereum network launched as the world’s first programmable blockchain, enabling developers to build websites, apps, and services on the decentralized infrastructure of blockchain.

Roughly speaking, 2015 marks the beginning of the transition from Web 2.0 to Web3.

This turning point made it so blockchains could do more than just send peer-to-peer transactions; they could be used to host things on the Web that normally relied on centralized servers. And that’s exactly how Web3 works: DApps are hosted on blockchains instead of centralized servers.

How Web3 works: blockchain and consensus among peers

For all intents and purposes, a blockchain is just a database: It can be used to log records of things like financial transactions. But unlike traditional databases, blockchains have no central authority or host. They can exist simultaneously on thousands of computers and servers, and be both used and shared by everyone in this large, decentralized group. Essentially, a blockchain is an open, publicly accessible, distributed ledger that can record transactions between parties. It can also store things like the programming for a particular app or website (which makes that service a DApp).

And this is one of the fundamental safety nets of Web3: Any record of a transaction has to “agree” with the thousands of copies of the ledger (or blockchain) hosted all over the world. In blockchain, this agreement amongst independent computers is called “consensus.” Because all the independent parties have to come to agreement about which transactions are valid, it’s nearly impossible for false or fraudulent transactions to sneak by. (Whereas in Web 2.0, it only takes one breach to steal or defraud: a hack of the central authority’s database.)

The Web3 advantage: returning control of the Internet to the people

One of the main benefits of Web3 is that it provides all the tools and decentralization needed to stop relying on central authorities like governments, Big Banks, or Big Tech. It gives users the chance to take control of the Web—to host their own sites and apps, transact freely with crypto, get better security (via cryptography), access services without Big Tech managing permissions, and overall avoid the centralized control of Web 2.0. The decentralization that’s baked into Web3 offers all kinds of benefits, and endless possibilities.

Without the control structures of Web 2.0, people are free to use the Internet as they see fit. There’s no limit to what can be created. Web3 is quickly becoming a place where users freely collaborate with one another. Developers are building innovative DApps without paying rent to Big Tech. Pretty much everything is open-source. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are giving users a chance to radically change how they interact with digital assets—creating value on the Web and actually owning it.

And all this is just the tip of the iceberg. Web3 is still very new. But like the versions of the Web that came before it, Web3 will soon become the new normal. Social media once seemed weird; now (for better or worse) we can’t imagine the world without it. People can finally make the Web work for them, instead of faceless Big Tech corporations. The question for users, developers, advertisers, and everyone else online is: Will you be left behind?

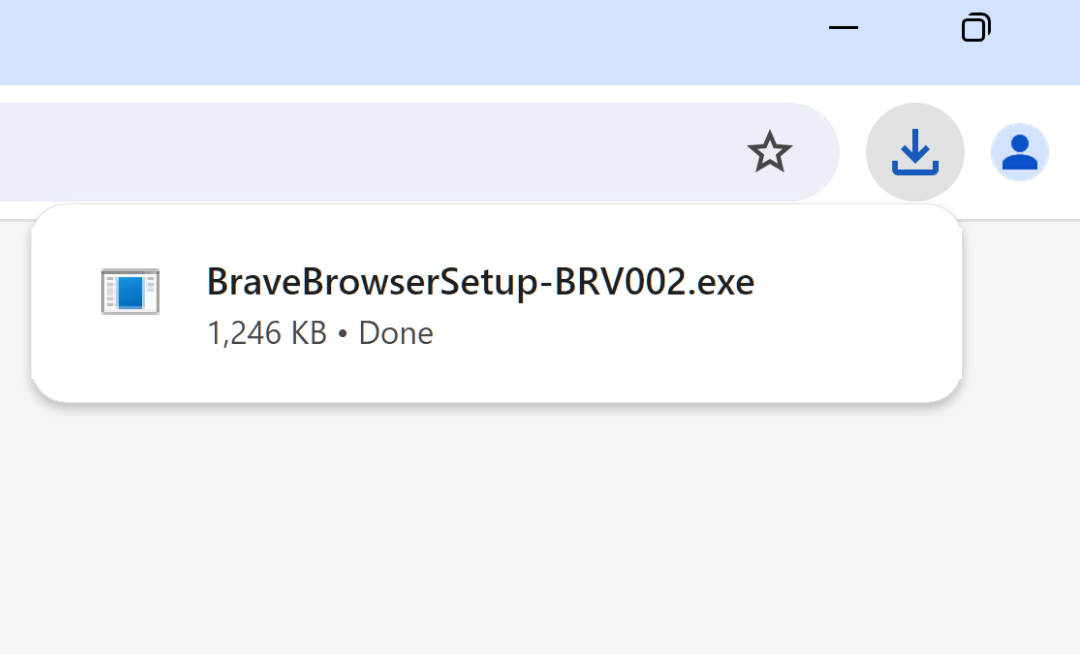

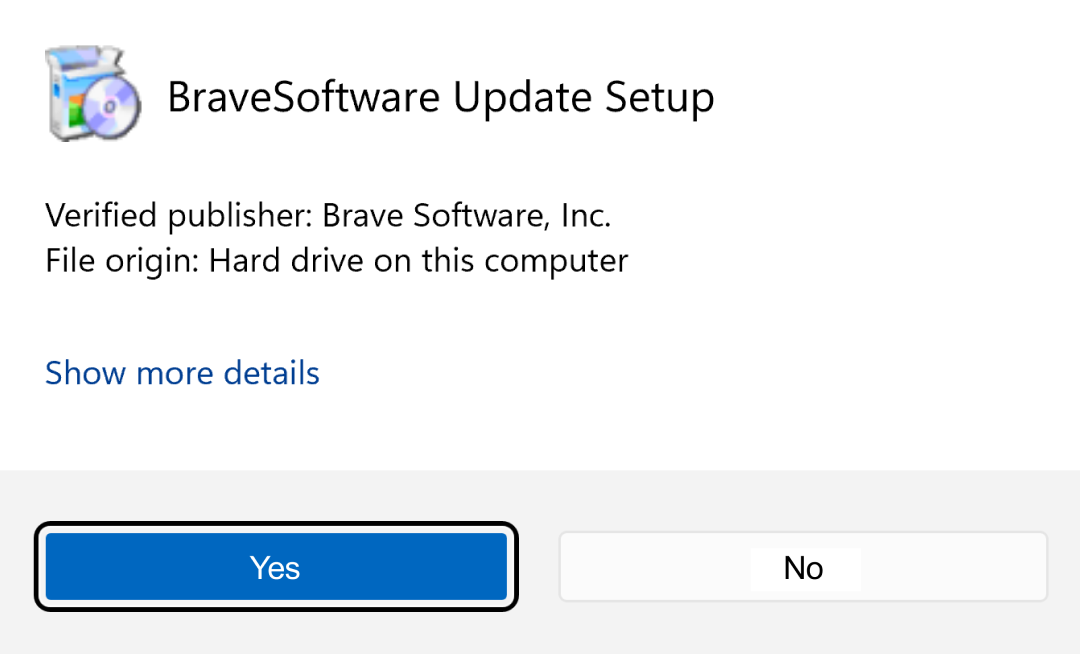

To start exploring Web3, all you need is a Web3-capable browser. Try Brave. It’s easy to set up, way faster and more private than your old browser, and blocks ads by default. With Brave, you can start using DApps and the decentralized Web in no time at all.