Europe’s top court signals new risk for marketers from ad tech

Latest updates: read more about the RTB complaints.

16 July 2018: A ruling of the European Court of Justice last month exposes marketers to severe legal risk from programmatic advertising.

The European Court of Justice ruled in the “Facebook fan page case” that a marketer is jointly responsible for the processing of personal data by the companies that it commissions, or causes to be commissioned, to provide it with targeted marketing.1 The marketer bears this responsibility even if it never directly touches to the personal data in question.

The text of the ruling has clear the implications for all programmatic advertising. Widespread data leakage, and an industry approach to consent that infringes the GDPR, means that the programmatic advertising system now exposes marketers to significant legal risk.

Context of the ruling

The European Court of Justice is the highest court in the European Union. Its ruling was prompted by a sequence of litigation that started in 2012. AGerman business school (called “Wirtschaftsakademie”) was using a Facebook fan page to market its services. In November 2011, it received an order from its local data protection authority2 to deactivate the fan page because users were not informed that (among other things)Facebook was dropping cookies on their machines.3 The business school complained about the decision. The data protection authority dismissed the complaint, saying that the business school

“had made an active and deliberate contribution to the collection by Facebook of personal data relating to visitors to the fan page, from which it profited by means of the statistics provided to it by Facebook”.4

A cascade of litigation followed. The business school brought an action against the decision in the Administrative Court (Verwaltungsgericht), arguing that the processing of personal data by Facebook could not be attributed to it. In October 2013, the Administrative Court annulled the data protection authority’s decision. The data protection authority then appealed to the Higher Administrative Court (Oberverwaltungsgericht), but this was dismissed. It then appealed to the Federal Administrative Court (Bundesverwaltungsgericht). At this point, the Federal Administrative Court put a stay on proceedings, and referred several questions for the European Court of Justice to rule on.

Overview of the Court’s ruling

The key question referred to the European Court of Justice was whether “an entity should be held liable in its capacity as administrator of a fan page on a social network … because it has chosen to make use of that social network to distribute the information it offers”.5 The Court observed:

“The fact that an administrator of a fan page uses the platform provided by Facebook in order to benefit from the associated services cannot exempt it from compliance with its obligations concerning the protection of personal data.”6

Therefore, the Court ruled that:

“the administrator of a fan page hosted on Facebook … must be regarded as taking part, by its definition of parameters depending in particular on its target audience and the objectives of managing and promoting its activities, in the determination of the purposes and means of processing the personal data of the visitors to its fan page. The administrator must therefore be categorized, in the present case, as a controller7 responsible for that processing within the European Union, jointly with Facebook Ireland…”8

The marketer is therefore not only responsible in a general way for the marketing campaigns that he or she pays for, but is specifically accountable as a “joint controller”, and therefore is subject to the full risk set out in Article 82 of the GDPR.9

Implications for programmatic advertising

For marketers, this is a momentous ruling. Its significance goes far beyond Facebook, and should frame how marketers view online advertising from now on. To understand why, consider three aspects of the Court’s ruling.

1. Directly or indirectly, it is a marketer who causes the data processing to occur.

The Court found that the marketer in question bore responsibility for Facebook’s processing of personal data because its decision to use a Facebook fan page as a marketing channel had caused the processing to happen. By using a Facebook fan page, a company “gives Facebook the opportunity to place cookies on the computer or other device of a person visiting its fan page, whether or not that person has a Facebook account.”10 The Court ruled that this is particularly significant when considering users that would not otherwise have been tracked by Facebook in this way:

“It must be emphasized, moreover, that fan pages hosted on Facebook can also be visited by persons who are not Facebook users and so do not have a user account on that social network. In that case, the fan page administrator’s responsibility for the processing of the personal data of those persons appears to be even greater, as the mere consultation of the home page by visitors automatically starts the processing of their personal data.”11

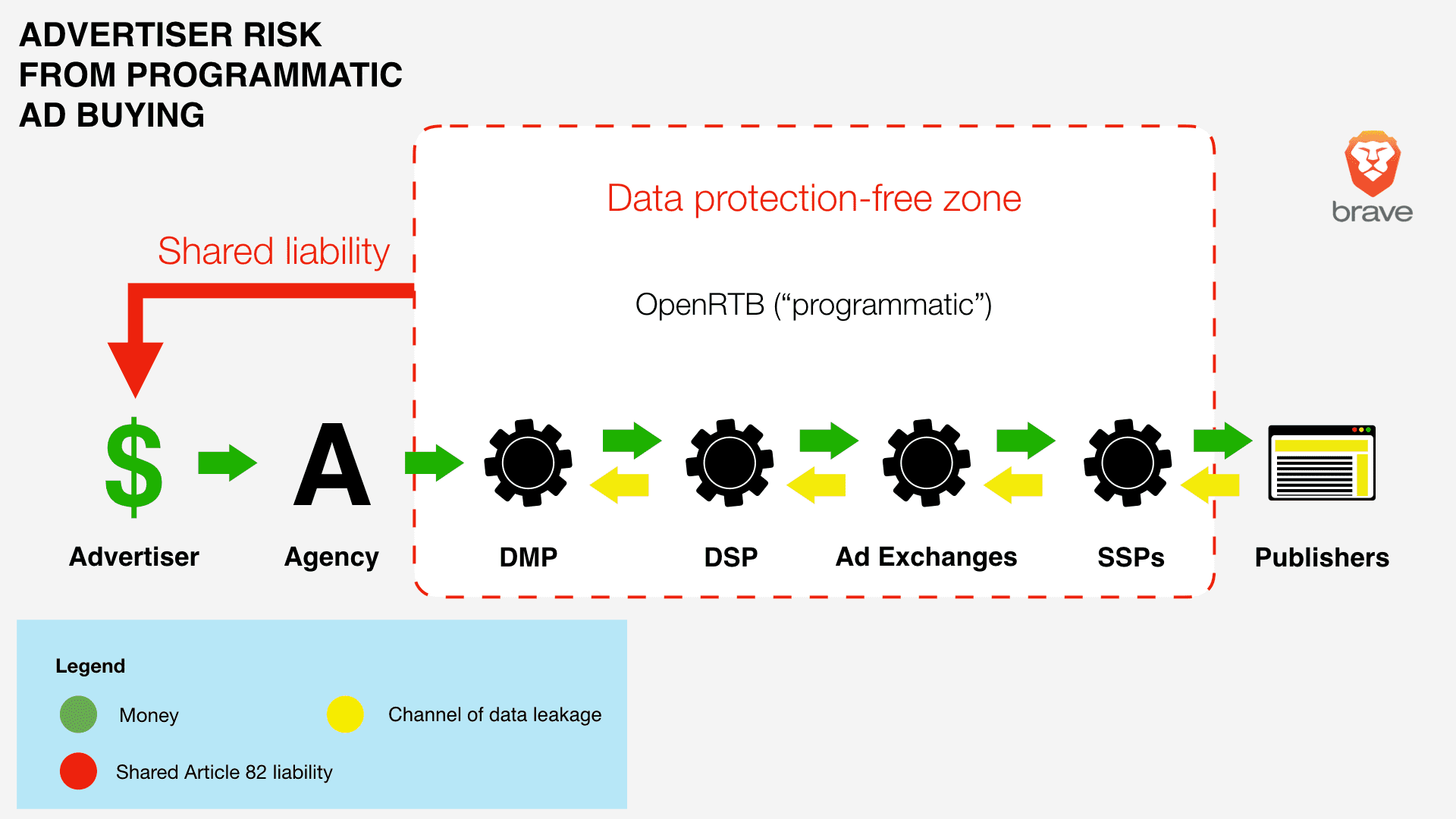

There is a direct parallel with programmatic advertising. By paying the online programmatic advertising system, marketers provide a reason for the adtech industry to process the personal data of every visitor to virtually every major website in every developed country. Every single time a person loads a page on a website that uses programmatic advertising, supply side platforms (SSPs) or ad exchanges send personal data about that person to tens – or hundreds – of companies to solicit bids from demand side platforms (DSPs). The DSPs act on behalf of marketers who might want to show an ad to that person.

This broadcast of personal data to multiple companies is known as an “RTB bid request”. Bid requests include the URL the user is loading, the user’s IP address (from which geographical position may be inferred) details of the user’s browser and device, and unique IDs (that may be used to build longer term profiles of that user).12 There is no control over what happens to these personal data13 once a website makes this data leaking “bid request”.

In other words, details about each page that every person visits on the Web, and details of their device, are shared with a large number of companies, constantly, on virtually every single website. Programmatic advertising is a vast and ongoing data breach,14 although one that goes unreported to regulators or data subjects – itself an infringement of Article 3315 and Article 3416 of the GDPR. This €10.6 billion17($12.3 dollar) system would not operate if marketers did not pay for it. The Court’s ruling means that they have to take responsibility for this problem.

2. The marketer requests targeting

The Court observed that marketers using Facebook fan pages define the target audience that they want to reach. This “has an influence on the processing of personal data for the purpose of producing statistics based on visits to the fan page”.18 Marketers using Facebook fan pages can “ask for — and thereby request the processing of — demographic data relating to its target audience”.19 These include:

“trends in terms of age, sex, relationship and occupation, information on the lifestyles and centers of interest of the target audience and information on the purchases and online purchasing habits of visitors to its page, the categories of goods and services that appeal the most, and geographical data which tell the fan page administrator where to make special offers and where to organize events, and more generally enable it to target best the information it offers.”20

This is precisely what programmatic adtech vendors promise their agency and brand clients, as a visit to an adtech vendor’s website will show.21 As the Court observed, by “designat[ing] the categories of persons whose personal data is to be made use of by Facebook … the administrator of a fan page hosted on Facebook contributes to the processing of the personal data of visitors to its page.”22 The same applies to any marketer who uses similar services.

3. The marketer requests reporting

The vendor (Facebook) processes personal data to enable companies using fan pages “to obtain statistics produced by Facebook from the visits to the page”.23 Even though the marketer may receive only anonymous audience statistics from Facebook,

“it remains the case that the production of those statistics is based on the prior collection, by means of cookies installed by Facebook on the computers or other devices of visitors to that page, and the processing of the personal data of those visitors for such statistical purposes”.24

Again, this has a clear parallel in programmatic advertising.

Risk for marketers

The ruling clarifies that marketers are actually “joint controllers”, accountable for the data leakage problems in the programmatic advertising system.25 As the Court noted, marketers are jointly responsible controllers, even though they may never touch the personal data themselves.26

The Court noted that “the existence of joint responsibility does not necessarily imply equal responsibility of the various operators involved in the processing of personal data”.27 Even so, the GDPR provides that “each controller or processor shall be held liable for the entire damage in order to ensure effective compensation of the data subject”.28 These court actions can be taken by people whose data have been misused,29 or by their representatives in some member states.30 Article 82 of the GDPR says that when a company has paid full compensation, it can then attempt to claim back proportionate compensation from the other parties involved.31

In addition to this, and to the fines that can be imposed by data protection authorities, it is also worth noting that the Member States may also provide for a claw back of all revenue generated through infringement of the Regulation.32

To avoid these risks, a marketer must be able to prove that all vendors that it has commissioned, or caused to be commissioned, are processing personal data in a fair, proportionate, and transparent manner.33 But this is impossible for marketers to do. Nor is it possible for a marketer to prove where the vendors working for it have got their data from, or to account for what happens to personal data once it is sent to large numbers of companies in RTB bid requests. The programmatic system was built to widely spread personal data, not to protect it. It is a data protection free zone.

This infringes many articles of the GDPR, most particularly Article 24,34 which concerns the responsibility of the controller, and Article 32,35 which requires security of processing. It also appears to infringe so many other articles of the Regulation that they are listed here in the footnotes.36

In addition, marketer accountability also means that the consent system designed by IAB Europe, an adtech trade body, puts marketers in further jeopardy. Where consent is unlawful, a data protection authority can impose the maximum penalty (4% of global annual turnover).37 The problem for marketers, as elaborated in more detail in a previous note38, is that the IAB Europe “transparency & consent” framework appears to be a serious and willful infringement of Article 5, Article 6, Article 8, Article 12, and Article 13 of the Regulation.

The IAB Europe approach conflates multiple data processing purposes, which the Article 29 Working Party has warned will render consent invalid. Article 5 of the GDPR requires that consent be requested in a granular manner for “specified, explicit” purposes.39 Instead, IAB Europe’s proposed design – and the various implementations of it live on the Web today – bundles together a host of separate data processing purposes under a single opt-in. For example, a large array of separate ad tech consent requests40 are bundled together in a single “advertising personalization” opt-in.41 This is despite European regulators having explicitly warned that conflating purposes in this way would render consent invalid.42

The IAB Europe descriptive text for the “advertising personalization” opt-in, for example, appears to severely infringe of Article 6,43 Article 12,44 and Article 1345 of the GDPR: in a single 49 word sentence, the text conflates several distinct processing purposes, and provides virtually no indication of what will be done with a reader’s personal data.46 In addition, some implementations of this consent approach prevent users from withholding their consent for non-essential processing of their data, which appears to severely infringe Article 7 of the GDPR.47 Even so, this approach to consent may be becoming a de facto standard for the programmatic advertising industry.48

Conclusion

Marketers are clients of a programmatic online advertising system that routinely shares personal data about the behavior of website visitors among large numbers of companies without any those data being protected. This data protection free zone now exposes marketers to liability. Therefore, so long as personal data are broadcast among hundreds of companies, marketers should exercise extreme caution about programmatic advertising.

Author Dr Johnny Ryan.

Thanks to Luke Mulks, Brendan Eich.