Brendan Eich writes to the US Senate: we need a GDPR for the United States

Brendan Eich, the CEO of Brave, has written to the US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, to present the case for GDPR-like data protection standards in the United States.

This note outlines why a GDPR-like standard in the United States is needed to spur innovation and prevent anti-competitive behavour by large tech platforms.

- The letter shows how the GDPR principle of “purpose limitation” can protect innovation by preventing the Google-Facebook “Duopoly” from using their scale in one area of business to crush new entrants in another area of business.

- It argues the importance of enabling frictionless data transfer with the many global markets that are embracing GDPR-like standards.

- It informs senators that the arguments of the tracking/adtech lobby have been discredited. Now, trust must be restored.

- It shows how a GDPR for the United States can relieve public concerns about political micro-targeting.

Postscript: As Brendan Eich wrote, the principles of the GDPR are American. After this letter was written, the United States again endorsed the core principles of the GDPR in Article 19.8 (3) of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

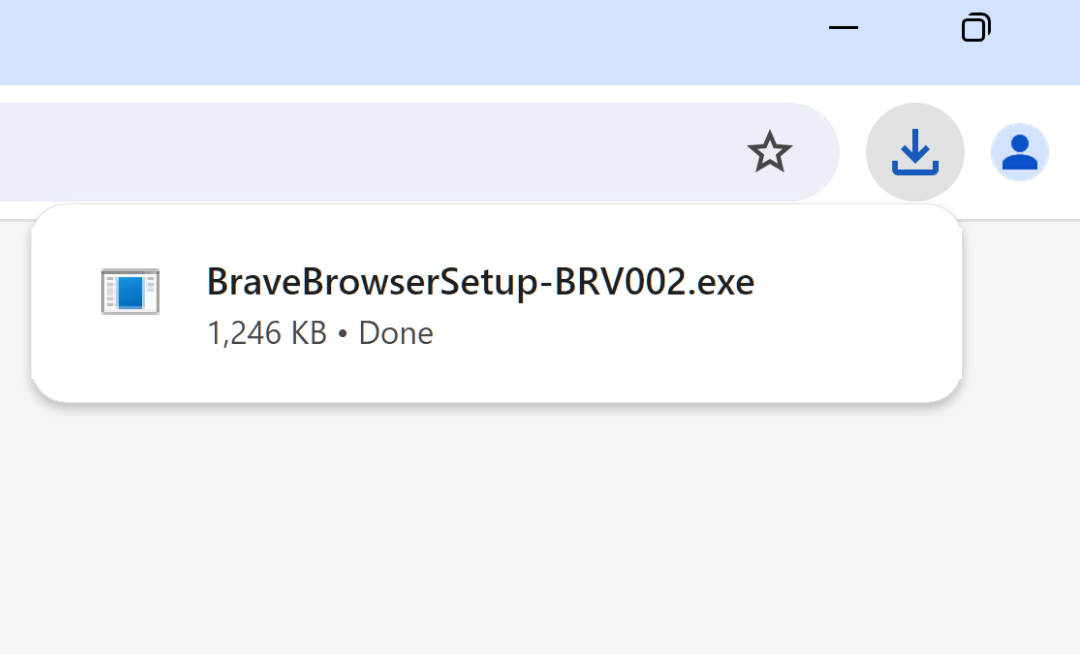

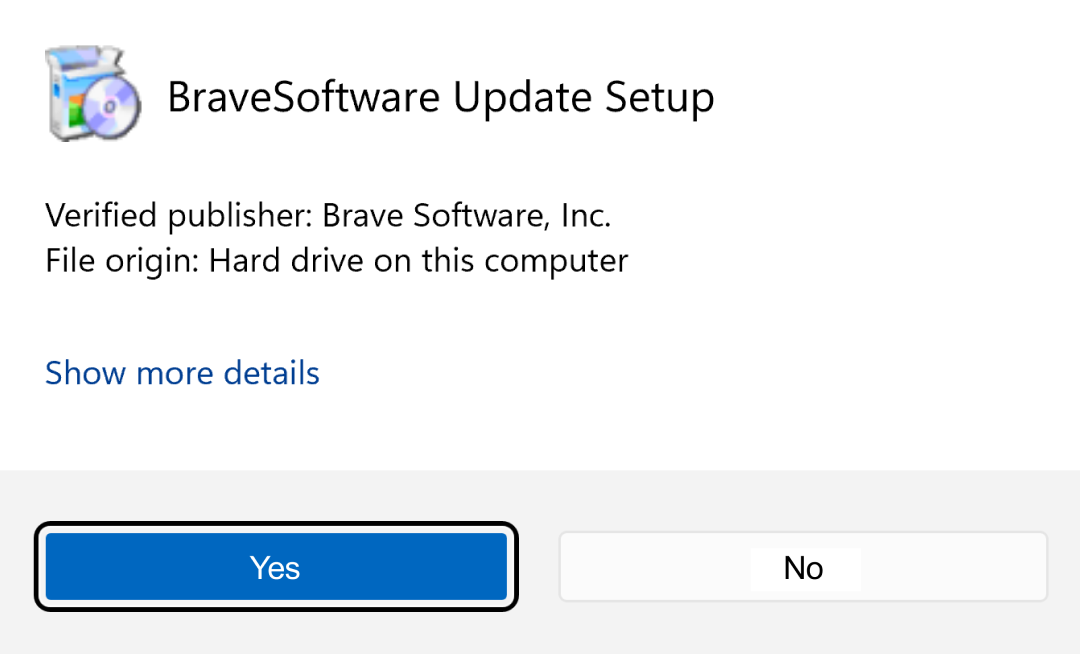

The full text of this letter is copied below. You can download the PDF here.

The Honorable John Thune Chairman Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation United States Senate 512 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510

The Honorable Bill Nelson Ranking Member Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation United States Senate 512 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510

28 September 2018

Examining Safeguards for Consumer Data Privacy

Dear Chairman Thune and Ranking Member Nelson,

I am the CEO of Brave, a rapidly growing Internet browser, based in San Francisco. I am also the inventor of JavaScript, and co-founded Mozilla/Firefox.

I write to commend the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation for engaging with this most pressing issue. It is our view as a company born and based in the United States, and as leading technologists, that the new framework for privacy regulation in the European Union represents a model that should be followed here.

I view the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as a great leveller. The GDPR establishes the conditions that can allow young, innovative companies like Brave to flourish.

As regulators broaden their enforcement of the new rules in Europe, the GDPR’s principle of “purpose limitation” will begin to prevent dominant platforms from using data that they have collected for one purpose at one end of their business to the benefit of other parts of their business in a way that currently disadvantages new entrants. In general, platform giants will need “opt-in” consent for each purpose for which they want to use consumers’ data. This will create a breathing space for new entrants to emerge.

The character of the GDPR is congruent with the United States’ understanding of privacy. Indeed, the primary principles of the GDPR are based on principles that the United States already endorsed in 1980, in the OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data. These previously endorsed principles include a GDPR-like definition of “personal data”. It is also worth noting that many features of the GDPR have been sought by the FTC for over a decade.

In the coming years, common GDPR-like standards for commercial use of consumers’ personal data will apply in the EU, Britain (post EU), Japan, India, Brazil, South Korea, Argentina, and China, for civil and commercial use of personal data. These countries account for 51% of global GDP. A common standard reduces friction and uncertainty, allowing companies from these countries to operate and innovate together with greater efficiency. A United States GDPR-like standard will ensure our position and competitive edge as leaders in technology and innovation in the global marketplace.

The online media and advertising industry

A GDPR-like standard in the United States will also establish the foundation of trust to enable innovation and growth. This certainly applies in our own online media and advertising industry. Contrary to some of our industry colleagues, I believe that it is not tenable for any platform, publisher, technology vendor, or trade body, to claim that they must track people in order to generate revenue from advertising.

The enormous growth of ad-blocking by people across the globe (to 615 million active devices by late 2017) proves the terrible cost of inadequately regulating the tracking-based advertising system. Trust will only return as the GDPR-like laws begin to curtail the online advertising industry’s worst practices.

The economic benefit of “behavioral tracking” to publishers’s businesses is questionable. The IAB, an ad targeting industry trade body, recently funded a lobbying study on “The economic value of behavioral targeting in digital advertising” that claimed that publishers (in Europe) rely on tracking for their advertising revenue. It is now public knowledge that a startling omission was at the heart of this report. Without any indication that it was doing so, the report combined Google and Facebook’s massive revenue from behavioural ad tech with the far smaller amount that actual publishers receive from it. Inclusion of Google and Facebook revenues enormously and incorrectly inflated the benefit that publishers derive from permitting ad tech companies to surveil and profile their visitors.

Political micro-targeting

The GDPR is also an important regulatory tool to fight political micro-targeting, and the attendant issues of micro-targeting. Currently, a person browsing the Web is tracked across nearly every webpage they visit by “online behavioral advertising” (OBA), which leverages persistent data collection to select the ads that are displayed. There is a massive and systematic data breach at the heart of this system that causes web users’ personal data to be leaked in such a way that can be harvested by unscrupulous data brokers. It is highly likely that this contributes to micro-targeting user data profiles.

Furthermore, so-called “dark ads” on websites, targeted using OBA, may be considerably less traceable than those served on social media, because the websites themselves are not aware of what ads they serve. Unlike Facebook, the OBA industry consists of a vast array of third party networks, operating behind the scenes with opaque processes, with no central authority to hold to account.

For these reasons, I urge you to consider the GDPR as a model to pursue. I would be delighted to provide further information, or to meet and brief you, to assist in your deliberations.

Sincerely,

Brendan Eich

CEO, Brave Software