Third-party cosmetic filtering

The TL;DR

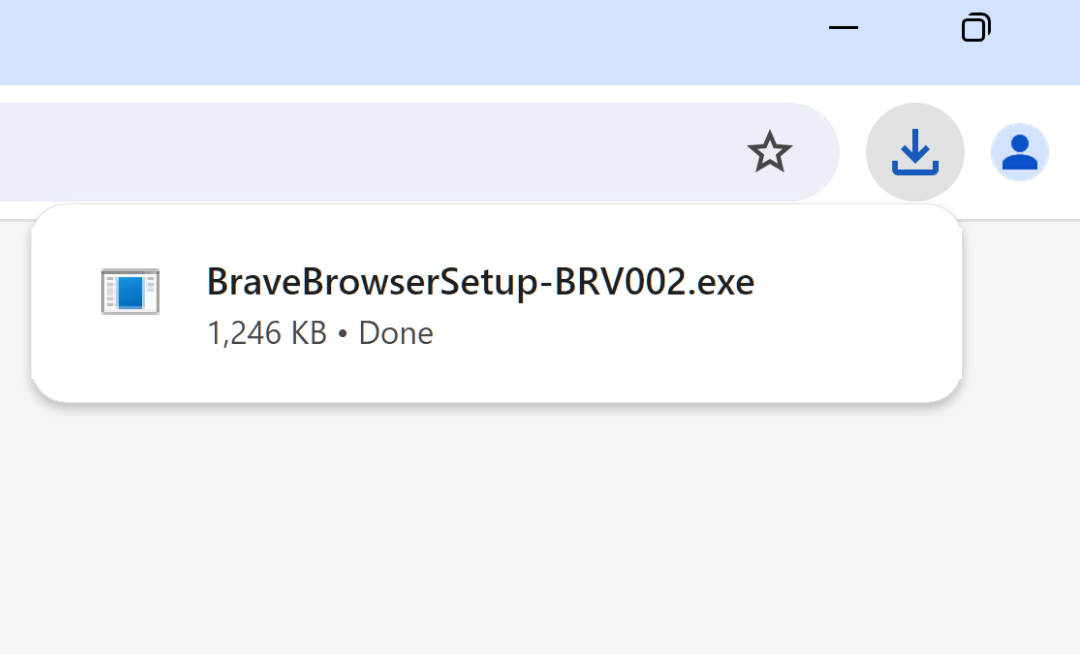

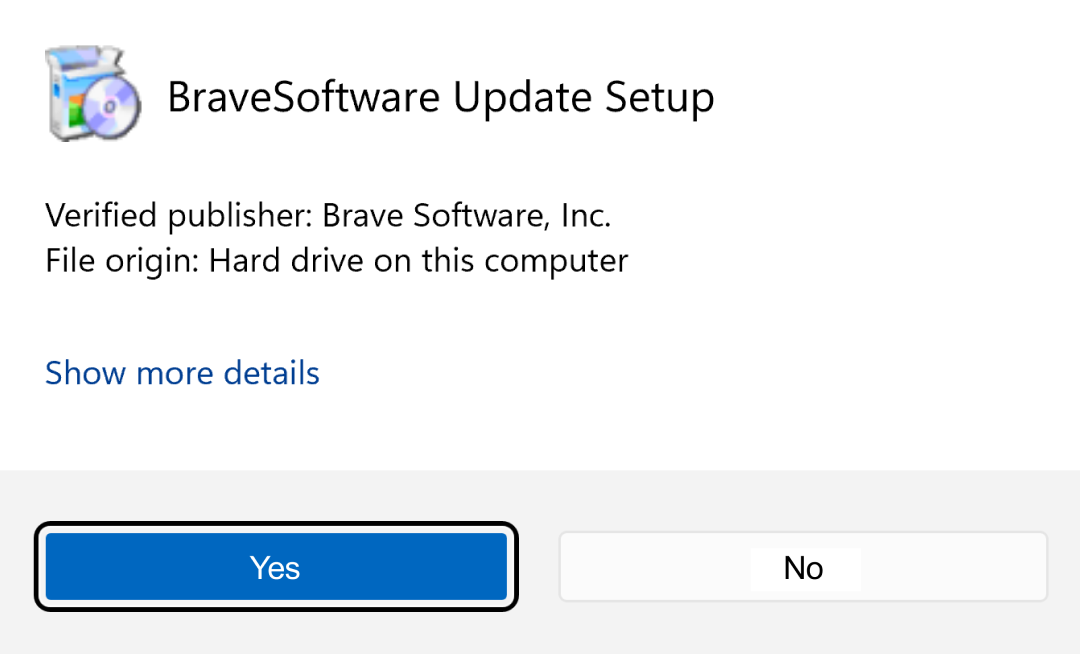

Brave is releasing a new system for hiding unwanted, privacy harming page elements. These include empty page space caused by blocking trackers, and third-party ads that cannot be blocked at the network layer. Brave’s system uniquely attempts to hide tracking third-party ads, while supporting sites that use privacy-preserving first-party ads. You can help test this system by downloading and using Brave Nightly. If everything looks good from testing, third-party cosmetic filtering will be in Brave’s stable release soon.

Problem: Blocking on the Network Layer Isn’t Enough

As discussed in a previous blog post, one way Brave protects Web privacy is by blocking (and sometimes replacing) network requests related to privacy-harming advertising on the web. This not only prevents advertisers and data brokers from tracking you on the web, but also improves performance, and makes the Web more pleasant visually.

However, sometimes blocking network requests to known trackers is not enough. In some cases this is because blocking privacy-harming advertisements leaves large empty blocks on websites (e.g. white space where the advertisements would have appeared); in other cases some unwanted advertisements are difficult to block on the network layer (e.g. advertisements served from unpredictable URLs, or advertising-content mixed with user serving content, etc.).

This post describes a novel way that Brave will start hiding page elements related to third-party tracking and third-party advertising, without harming first-party, privacy respecting advertisements. Brave’s approach is unique, and designed to improve Web browsing for users without harming sites that respect user privacy. Before describing the unique way Brave does this, we first need to give some background on how most ad-and-tracker-blocking on the web works.

Background: How Filter Lists Work

Brave, along with many other popular Web tools like AdBlock Plus and uBlock Origin, use filter lists to determine which Web resources to allow, and which to block. EasyList and EasyPrivacy are the two most popular such lists, but many other lists exist too, targeting language or interest specific parts of the web.

Filter lists, broadly speaking, consist of two types of rules: network rules, which describe URLs that should be blocked, and cosmetic rules, which describe page elements that should be hidden. These are distinct, but often work in tandem. For example, a network rule might block a request to a privacy-harming third-party iframe, and a related cosmetic rule might hide the page element that the iframe was placed in, to prevent an unseemly empty space from appearing in the page.

Filter list authors do not label whether a cosmetic rule targets first-party ads, third-party ads, or both. In general this is because most tools using these filter lists are not concerned with the distinction. Brave though, is different; we want to block privacy-harming third-party ads, but allow privacy-preserving first-party ads.

Hide Privacy-Harming Ads, But Leave Privacy-Respecting Ones

While Brave uses many of the same filter lists that other tracking and ad blocking tools use, Brave’s mission differs from existing filter list using tools; Brave aims to protect privacy and browsing aesthetics, without harming sites that are privacy-respecting. Put differently, Brave aims to block third-party trackers and ads (which are, in practice, often indistinguishable), without affecting solely first party ads.

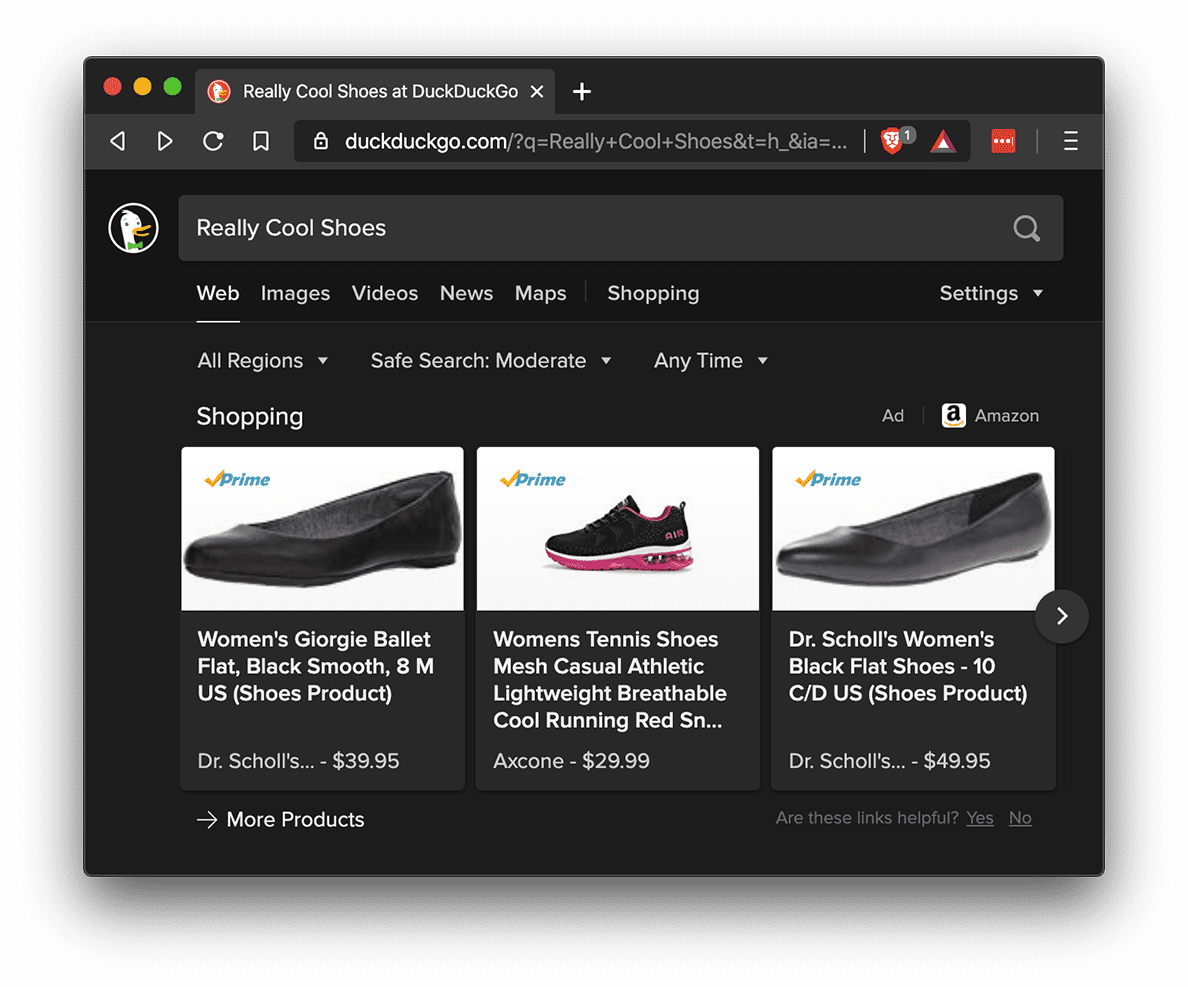

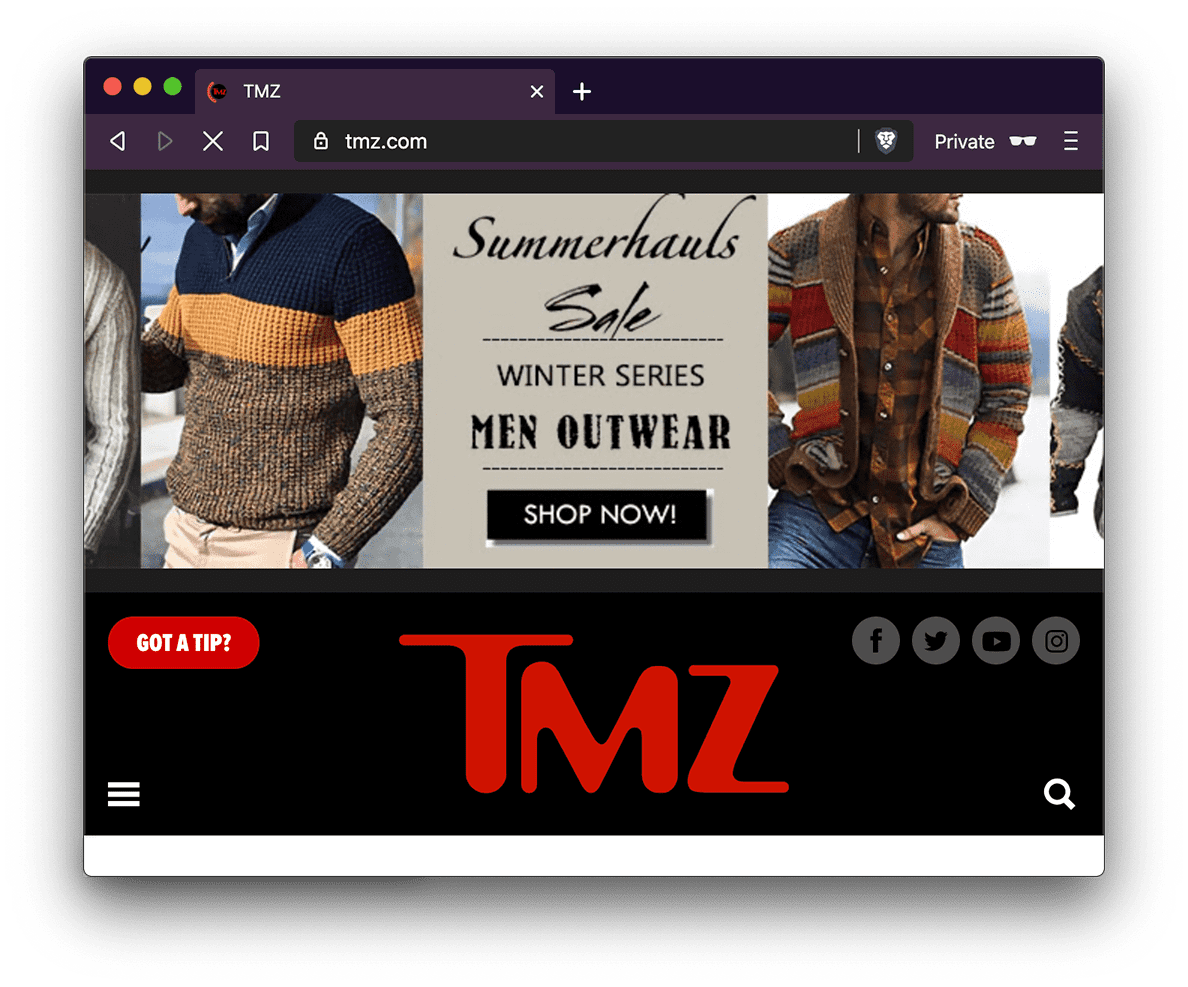

An example of a privacy-respecting first-party ad (left, from duckduckgo.com) and a privacy-harming third-party ad (right, from tmz.com). Even though the DuckDuckGo example shows images from Amazon, the images are served from duckduckgo.com servers, preventing Amazon from tracking you. In the right example though, the clothing ad comes from Google’s servers, allowing Google to track your browsing behavior.

To date, Brave has not applied cosmetic (i.e. element hiding) rules for two reasons: (i) we expect network blocking prevents most privacy harm, and (ii) we did not have a good solution for distinguishing cosmetic rules that hide first-party ads (which we want to allow) from cosmetic rules that hide third-party ads (which are frequently privacy harming, and so we wanted to hide those). As a result, we so far have applied network rules from filter lists, and not applied any cosmetic rules; a useful, but not satisfactory compromise.

Solution: Hide Third-Party Ads, Show First-Party Ads

However, beginning today with our Nightly release channel, Brave will start applying cosmetic filter rules to further improve browsing the Web in Brave. Our approach is to make a best-effort, runtime decision about whether a cosmetic filter list rule would hide only third-party advertisement content, including empty page space caused by blocking third-party ads at the network layer. If a cosmetic rule would hide a first-party ad, we do not apply that cosmetic filter list rule.

Brave’s approach is designed to balance performance and accuracy. Taking too long to decide whether a cosmetic rule would block first-party ads would unacceptably degrade browsing performance, while a system that frequently hides first-party ads would be incompatible with Brave’s mission.

Our approach is open source and auditable by anyone interested in the specific approach, but at a high level our approach works as follows:

- For each cosmetic rule that applies to a page, periodically check to see if the rule matches any elements on the page. If no elements match, check again later.

- If the cosmetic rule would hide first-party images or resources, do not apply the rule.

- If the cosmetic rule would hide any elements that include no images or resources (e.g. a text-only ad), do not apply the rule.

- Otherwise, apply the cosmetic rule and block the third-party ads.

Brave’s Cosmetic Filtering and Continuing Improvements

You can try Brave’s system for third-party cosmetic filtering by downloading and running Brave from our Nightly release channel. This version of Brave includes new features still being tested. We’re eager to get feedback and hear your thoughts about our new, unique system for hiding third-party ads, without harming privacy respecting sites.

Our system for third-party cosmetic filtering is just one of many new privacy-protecting, Web improving features we’re releasing in Brave. Look for the next post in this series describing more new, unique, user-serving features in Brave!