Governments and regulators around the world are imposing new legislation aimed to limit the control of Big Tech monopolies. One such attempt is the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), which seeks to foster “fair and open” digital markets. The DMA applies to Big Tech services designated as “gatekeepers,” which in this case means a large digital platform providing services that can include search engines, browsers, app stores and messenger services. Some tech companies considered gatekeepers are Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Google, Meta, and Microsoft.

The DMA seeks to address monopolies in these gatekeeper platforms and services that might otherwise prevent competition (specifically by imposing obligations and prohibitions on those gatekeepers). Choice screens are one key aspect of the obligations the DMA sets out.

Note: This isn’t the first time that regulators have resorted to choice screens to attempt to break up tech monopolies. Previous attempts occurred with less-than-desirable results, including Google auctioning slots on a previous Android search engine choice screen. However, the DMA is more comprehensive in nature, holding gatekeepers responsible to proactively meet its obligations or face significant fines and “additional remedies.”

Why do we need choice screens?

Without sufficient regulation, Big Tech companies have used their privileged position as platform owners to stifle competition across various tech industries—encouraging or defaulting users to their own products and apps and dissuading or preventing users from trying alternatives. For example, Google as the default search engine in Chrome, or Safari as the default browser on Apple devices.

Choice screens intend to help users more easily learn about—and opt to use—alternative browsers from third parties. While some users will make these kinds of choices on their own, the vast majority simply use the default software on their computers, tablets, and phones—this further expands the controlling power of Big Tech. Choice screens, in theory, help make the digital marketplace more fair and open—potentially reducing Big Tech’s overwhelming market share and carving out some room for competing software to exist. And, ultimately, the diversity and competition of a fair and open market should benefit end users.

What are choice screens?

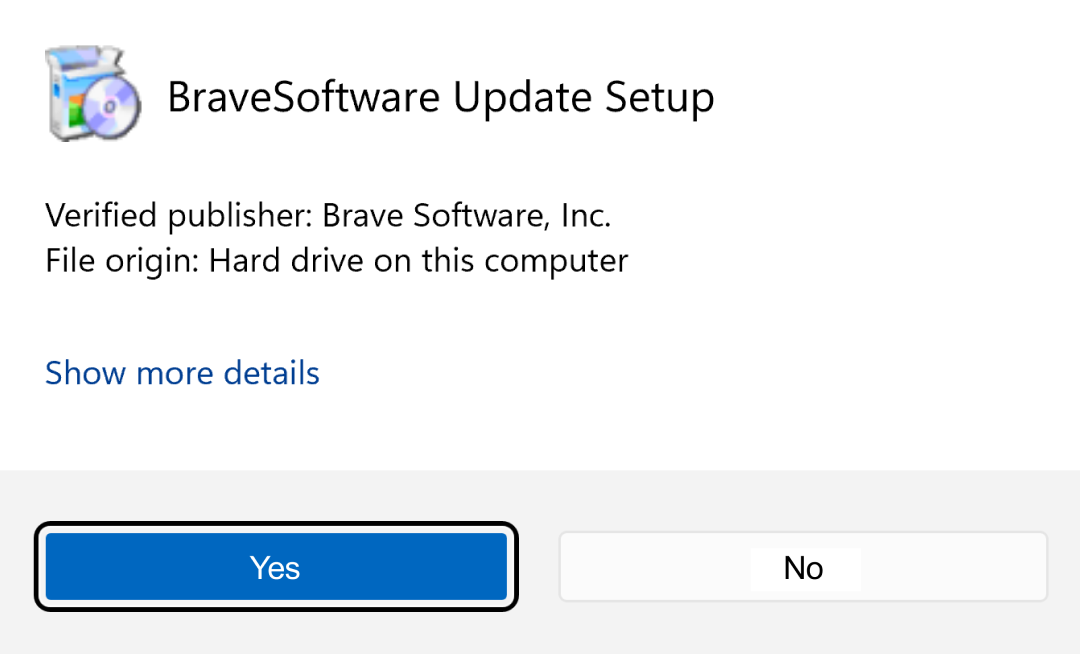

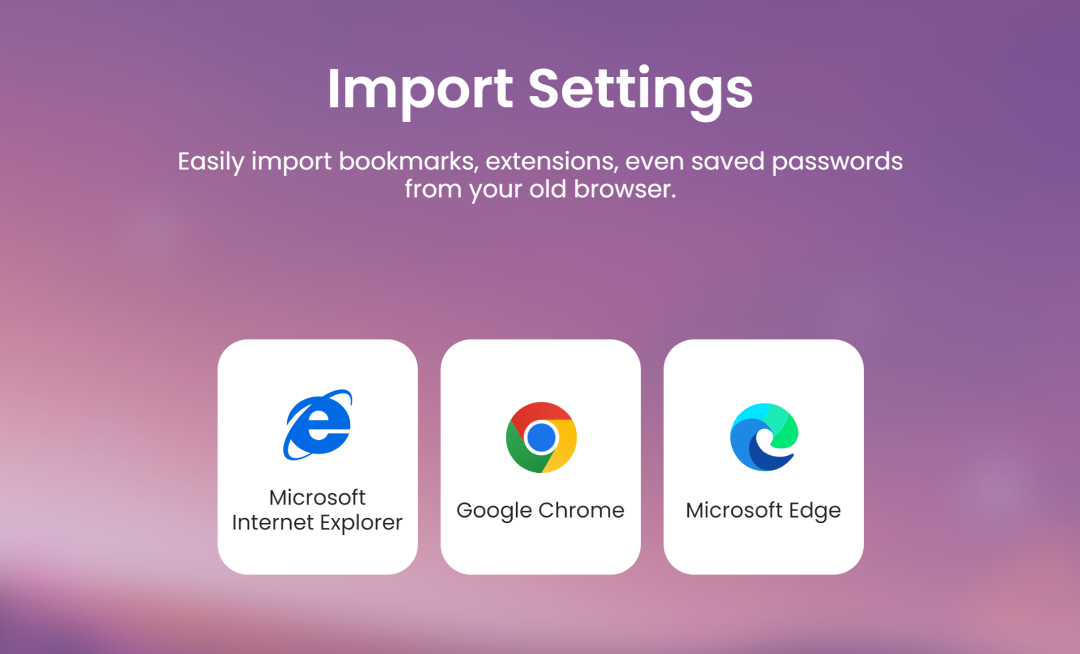

Choice screens are essentially a piece (or screen) within the user interface of a device. Generally speaking, they should look and feel similar to any other part of the user interface (e.g. a settings menu). These screens should list a set of choices for a user to select from, and potentially a matching description, icon, or other relevant information. What each choice screen actually looks like, however, is up to its creator (in this case, Apple or Google). There could be slight variances in their appearance and format, when and where they appear to users, how much information they display, and more.

Note that the fact Big Tech companies have control over how choice screens appear is a topic of debate, and arguably has major implications for the effectiveness of choice screens.

Right now, the DMA-mandated choice screens only apply to Web browsers and search engines (though the DMA could expand the scope of choice screens to include other apps/software in the future). This means that, for now, in the EU market users are presented with a list of available browsers and search engines to set as the default on their mobile devices.

Browser choice screens

Web browser choice screens ask users to select a browser to assign as their device’s default. Browser choice screens make it easier for users to choose alternative browsers to Chrome and Safari, which are the only two browsers currently considered popular enough to be regulated by the DMA—no doubt mostly due to their status as the default browsers on Android and Apple devices, respectively.

Many argue that browser choice screens should appear when first setting up a new device (like a mobile phone, tablet, or desktop computer), after major software updates or a reset to factory defaults, or be accessible at any time via a settings menu. In other words, gatekeepers shouldn’t make browser choice screens difficult for users to find.

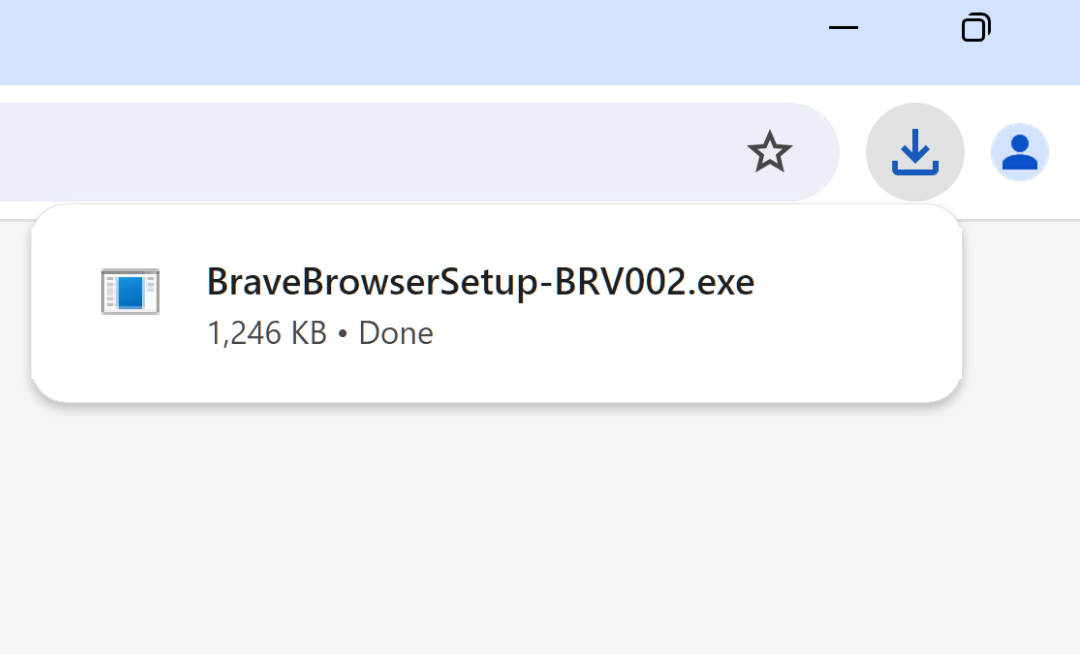

In practice, browser choice screens have been configured to trigger with different conditions. Google’s browser choice screens are triggered when setting up a new Android device (meaning those with already-setup Android devices won’t see the screen at all). Apple’s browser choice screens are triggered when opening the Safari browser on iOS 17.4 (meaning only devices updated to iOS 17.4 or later can trigger the choice screen). In both cases, the only way to encounter the browser choice screen more than once is to factory reset the device, and set it up like new again.

Interested in choosing an alternative browser with real privacy and security improvements? See how Brave compares to Chrome and how Brave compares to Safari.

Search engine choice screens

Search engine choice screens currently only apply to one search engine: Google. It’s not surprising; Google maintains ~90% of search engine market share worldwide, again in large part thanks to its default status on many Android and Windows devices, as well as Apple devices via high-profile agreements between Apple and Google.

On Android devices, a search engine must be chosen upon setting up a new device. On platforms other than Android, Google’s search engine choice screen will appear when installing Chrome (or updating to the relevant version). Despite Google being the default search engine on Apple’s Safari browser, there’s currently no search engine choice screen for users to choose an alternative. But this is a rapidly evolving landscape, and there will likely be some solution soon.

Interested in a private search engine that doesn’t profile you? Brave Search is built on an independent index of the Web, offering high-quality search results without ties to Big Tech. And it can easily be set as the default search engine on almost any browser or device.

Reception and implementation of choice screens

Many consider the implementation of choice screens to be a significant blow to Big Tech monopolies, and a welcome benefit to user choice. But there’s plenty of criticism and debate about when, where, and how choice screens are triggered—and how Big Tech gatekeepers can undermine their intended purpose.

Potential problems with the implementation of choice screens

As with most regulations, it’s safe to assume Big Tech companies view DMA choice screen mandates as a nuisance and yet another challenge to their old way of acquiring (and keeping) their users. Big Tech will aim for bare-minimum solutions that satisfy regulators while minimizing the number of users they lose to third-party alternatives. They won’t voluntarily design choice screens that can significantly impact their bottom line.

In other words, when companies like Google or Apple are responsible for creating their own choice screens, they have a clear incentive to render those screens ineffective. Some potential measures that could sacrifice the fairness of choice screens include:

- Surfacing choice screens at inconvenient times (e.g. when opening the browser or when trying to play a video)

- Not surfacing choice screens often enough (e.g. the choice screen is only available once upon initial setup)

- Making choice screens easy to skip without selecting a default

- Using design elements (like branding, colors, and other cues) to influence choices

- Curating the list of choices in some non-random way (e.g. giving well-known options priority placement)

- Not displaying relevant descriptions (or using unfair descriptions) of third-party alternatives

- Overpopulating the list of third-party alternatives with hard-to-use or less viable options to induce decision fatigue

- Making third-party alternative apps harder to find once downloaded

- Using notifications to subvert a user’s choices (e.g. “Are you sure you don’t want to use Chrome instead?”)

Apple’s browser choice screen rollout, for example, has been met with major criticism. Critics don’t like that it fails to define what a browser is, only appears when a user opens Safari (i.e. when a user is already intent on doing something else, not making a setup-level decision about their device), and lacks descriptions for alternative browsers. Most industry watchers would argue that giving users information about the choice and what they’re choosing is crucial to informed decision making.

Google’s choice screens are—by comparison—more fairly designed. They describe what a browser/search engine is, provide descriptions of Chrome/Google alternatives, and appear during device setup.

How choice screen options are determined

Since Google and Apple design their own choice screens, they have significant control over which third-party search and browser alternatives make the cut. Apple has eligibility criteria for inclusion on its browser choice screen list. And Google provides both browser choice screen eligibility criteria and search engine eligibility criteria.

The gist of the requirements is that third-party browsers or search engines that make it onto choice screen lists must be legitimate (i.e. meet basic security measures), legally compliant in certain jurisdictions, and have a sufficient degree of popularity. Notably, choice screen listings can (and often do) vary by country.

The impact of choice screens on your browsing and search experience

Will choice screens really alter market dynamics and competition in the tech industry? That’s what regulators hope. Ultimately, the impact of choice screens is up to users. The effectiveness of choice screens will be determined by how many users actually educate themselves about browsers and search engines and choose a new alternative.

For users, browser and search engine choice screens could be nothing more than a few extra pop-ups to deal with, or they could present a meaningful opportunity to improve their experience online. A choice screen might help you discover a new option that makes browsing and searching easier, faster, safer, or more private.

In any case, choice screens point to the idea that users should have access to more transparent information (e.g. privacy policies and data usage practices) about the apps they use, and easy access to make an informed decision about alternative options. People shouldn’t be coerced into accepting the Big Tech defaults.

If you’re ready to try a secure, private browser or search engine that puts users first, check out the Brave browser and Brave Search.