Privacy Sandbox is Google’s latest attempt to phase out harmful third-party cookies and cross-site tracking, in favor of more private Web standards in their Chrome browser. And these changes are privacy-improving (at least, they are when compared to how Chrome operates today; these improvements still fall short of private-by-default browsers like Brave).

But while most users—if they truly understood the privacy harms—would want a transition away from third-party cookies, Google’s Privacy Sandbox really has a different aim: to preserve the status quo control Google currently enjoys over a majority of online advertising (and the revenue they earn from it). As the world’s largest ad platform, Google has a strongly vested interest in maintaining its ad targeting capabilities. So, in the name of preserving its bottom line, Google’s cookie alternatives are—in many ways—not aimed at privacy at all. Rather, they’re designed to solidify Google’s monopoly over the Web…and online advertising.

What is the Privacy Sandbox?

Understanding Google’s proposed Privacy Sandbox first requires a basic understanding of how the Internet remains (mostly) free for users.

The Privacy Sandbox is based on the idea that the Internet as we know it today—a rich resource of information, tools, and entertainment—is only made possible by advertising revenue. The problem (which even Google admits) is that the traditional online ad industry is built on technologies that harm user privacy—namely third-party cookies and trackers (which enable cross-site tracking and personalized ad targeting). The tracking-powered ad industry, or surveillance economy, makes it so users can be identified and tracked online, and that the collected data can be bought, sold, and shared more widely than most people would like.

The Privacy Sandbox is meant to preserve personalized ad targeting so the Internet can keep running like it always has (i.e. free), but with some privacy improvements (again, improvements relative to the Chrome of today). Specifically, the Privacy Sandbox aims to:

- Minimize the data that’s collected about individual users

- Make current tracking mechanisms obsolete

- Give users more control over how their data is used in the ads they see

- Provide more transparency about the type of tracking and data collection that’s occurring

But again, ultimately the Privacy Sandbox is intended to sustain Google’s revenue stream.

How the Privacy Sandbox works

While the Privacy Sandbox in isolation does offer some modest privacy improvements to the way Chrome works today, it also consolidates control for Google. Some of the instruments (either included in, or adjacent to, the Privacy Sandbox) that maintain Google’s power include:

- Topics API: a consolidated ad-targeting mechanism based in Chrome

- Protected Audience API: an auction-based system—informed by Topics—for determining which ads will be displayed to certain users

- Manifest V3: which weakens and restricts browser extensions like ad blockers

- Related Website Sets: which allows multiple sites to act as the same site, and share user data accordingly

- Web Bundles: which enables sites to load without the source URL the resource came from, so any extra tools to block ads or otherwise modify the page won’t work (this is similar to what Google’s AMP does for mobile browsing)

- Signed Exchanges: which allows one organization to serve sites on behalf of another, obfuscating where you’re actually fetching data from

To learn more about all the privacy implications of these (and other) components, check out Brave’s post about concerns with the Privacy Sandbox. For now, we’ll focus on one aspect of Privacy Sandbox of particular interest to brands and advertisers: Topics.

How the Topics API works

Topics is Google’s latest technique to deliver personalized ads. It works like this:

As you browse in Chrome, instead of encountering third-party cookies placed by advertisers and tracking companies, the browser itself will track your browsing activity and match it to a list of several hundred advertising “topics.” Sites that use the Privacy Sandbox would then “ask” Chrome (specifically the instance of Chrome you’re running locally on your device) what topics you’re interested in, and display ads it’s assumed are relevant to you.

Topics helps advertisers learn about your relevant interests, then the Protected Audience API introduces a new method for determining which ads you actually see: the auctions for ad space now happen locally in your browser (rather than in third-party communications with ad providers). When you visit a site that displays ads via the Privacy Sandbox, an auction takes place where advertisers compete to outbid each other; the winner(s) get the ad placement(s).

It’s a marginal privacy improvement, but comes with a major downside: browser bloat. To carry out on-device ad auctions, your local instance of Chrome will download and carry around all the ads and other resources relevant to you in a catalog stored in your browser. The on-device auctions also mean your browser might be loading javascript from, say, 50 different advertisers at once just to determine which ad you’ll see. In this way, users will pay for a bit more privacy with their device resources: speed, available memory, and battery life will take major hits.

Evaluating the Topics API

Topics does improve on earlier failed techniques (like FLoC) in that the list of ad topics is publicly available. You can also choose to remove topics you don’t want to be targeted for, or opt out altogether.

But the obvious critique of Topics—aside from how resource-intensive it will be on a user’s device—is that it puts Google in control of even more of the online ad ecosystem. Instead of being tracked by many different websites and tracking companies, you’re only tracked by Chrome. Google becomes even more central to ad-targeting data.

And, while that tracking is happening on-device as opposed to on Google’s servers, the derived topics are shared with any participating website—and every script operating on the page. This, in practice, means lots of people are learning a lot about your browsing history, and device performance will suffer.

Topics establishes Google as the centralized power between advertisers and users, and exposes information about your browsing history to far too many parties. But the much larger privacy harm comes from how the other parts of the Privacy Sandbox come together to cement Google’s control over the Web. In short, with the combined power of Web Bundles and Signed Exchanges, Google can make it appear like you’re being served content from another site (e.g. nytimes.com) when in fact the content you’re reading is coming from Google’s servers. This creates a scenario where Google can insert itself in the middle of virtually all Web traffic in Chrome.

While the Privacy Sandbox in isolation does offer some modest privacy improvements in Chrome, it will likely harm (not help) user choice and user autonomy, and overall increase Google’s control over the Web. For users, this could lead to privacy harms down the road; for advertisers, this could lead to less control over ad pricing and performance.

Brave Ads: personalized ads with real privacy

Despite what Google would have you believe, it’s possible to target users with relevant ads and still protect user privacy, too. In fact, that’s exactly why Brave developed its private-by-design ad platform, Brave Ads.

Brave Ads protects user privacy and offers advertisers actionable insights on high-performing ads.

Brave offers four discreet ad units:

- Keyword-based search ads in Brave’s independent, global-scale search engine, Brave Search

- Full-size images that appear in new tabs in the Brave browser

- Push notification ads in the Brave browser

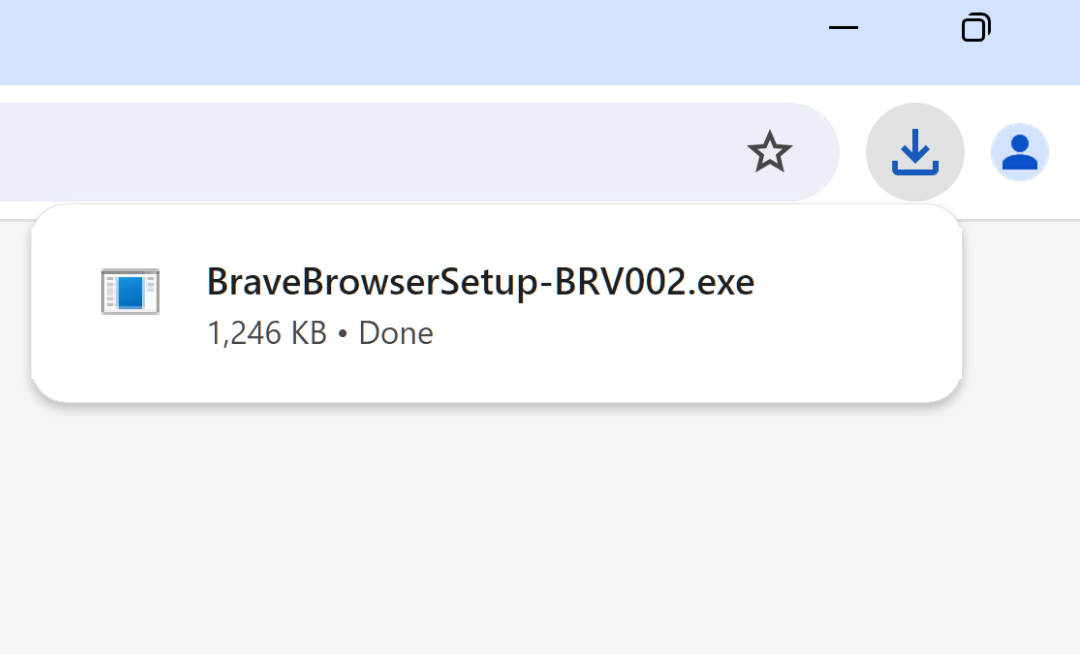

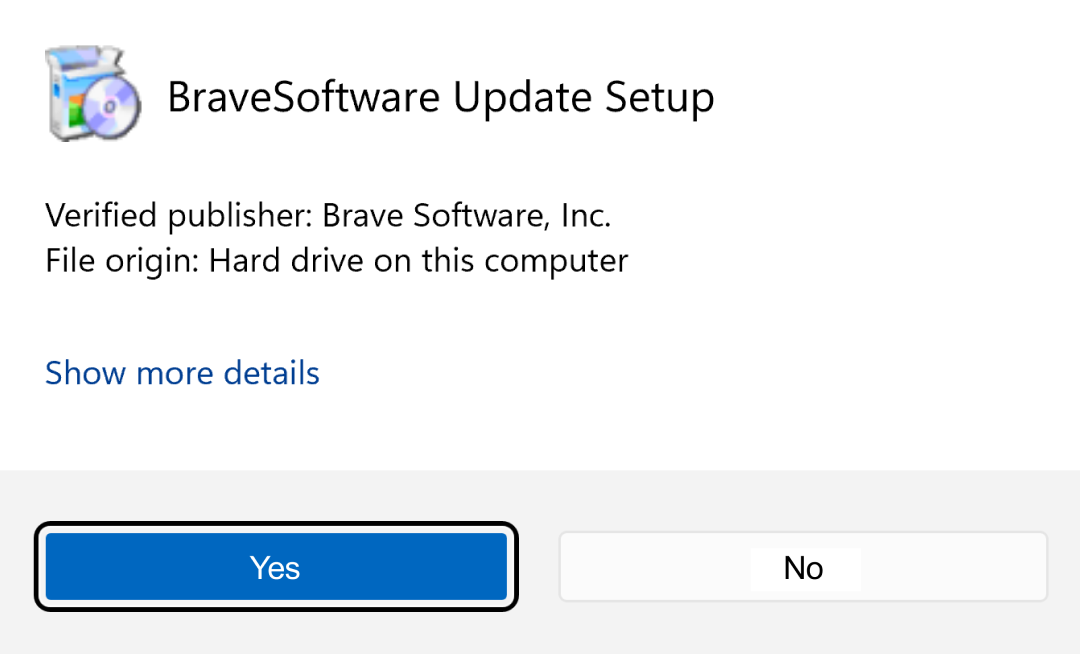

Brave Search ads are matched to a user’s search query; on the browser side, the Brave Ads server creates a catalog of ads and targeting parameters, which is downloaded to the Brave browser on a user’s device. Then, these ads are matched locally to users directly in their browser, without any personal data ever making it back to Brave’s servers, or even leaving a user’s device.

Brave Ads vs. Privacy Sandbox

Though both Brave Ads and the Privacy Sandbox offer private, on-device ad models, there are several key differences:

- Chrome shares your Topics profile (a proxy for your browsing history) with any site—and any script on any site—that requests it

- Brave intentionally doesn’t share any of your on-device info with anybody—it never leaves the browser

- Chrome consumes valuable device resources (i.e. battery and memory) with resource-intensive ad auctions

- Brave doesn’t tax your device with ad auctions

- Chrome is “heavier” because it must carry around resources from ad providers as well as ads themselves (one ad might be as large as the entire Brave Ads catalog)

- Brave has significantly smaller, lightweight (i.e. text-based) ads, as its not trying to show the on-page or video-based ads you would find in other ad units

Above all, Brave Ads is proof that it’s indeed possible to maintain a thriving online ad economy—including real ROI for advertisers—while putting user privacy first. Privacy and ROI don’t have to be at odds; that’s just a fake devil’s bargain that Big Tech companies like Google want you to think is unavoidable.

Instead of allowing these tech giants to consolidate power and control over the online ad industry with initiatives like the Privacy Sandbox, advertisers should look toward the truly private alternatives that users want. And with alternatives like Brave Ads, advertisers can give users what they want without sacrificing ROI. Just look at the performance data behind Brave Ads:

- 3% blended CTR across all ad placements

- 17% average lift in purchase intent

- 28% average lift in brand perception

- 64% average lift in brand/promotion awareness

Visit Brave Ads to get started with your first private ad campaign today.