Latest updates: read more about the RTB complaints.

Brave has written Californians for Consumer Privacy to support its new CPRA privacy law proposal, and to recommend several privacy enhancements.

Brave makes several recommendations. First, the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) should cover all information that can single out an individual. Second, the CPRA should adopt the “legal basis” model of the GDPR. Third, the scope of a processing purpose should be defined, in order to protect Californians from being subject to a commercial surveillance free-for-all.

Brave also queries whether the CPRA should have tighter provisions on notification and de-identification. Additionally, Brave suggests that CPREA’s allowance for sharing individual Californian’s opt-out choices among many companies may paradoxically undermine privacy protections.

Brave also suggests that adopting a risk-based approach would further protect small businesses that create minimal privacy risks from regulatory burden, and place the emphasis of scrutiny and enforcement on big businesses that create big privacy risks. Finally, we recommend that enforcement power include not only financial sanctions, but the ability to impose bans on processing.

Alastair Mactaggart

Chair

Californians for Consumer Privacy

1020 16th Street, Suite #31

Sacramento CA, 95814

28 October 2019

Brave’s response to request for comment on CPREA draft

Dear Colleagues,

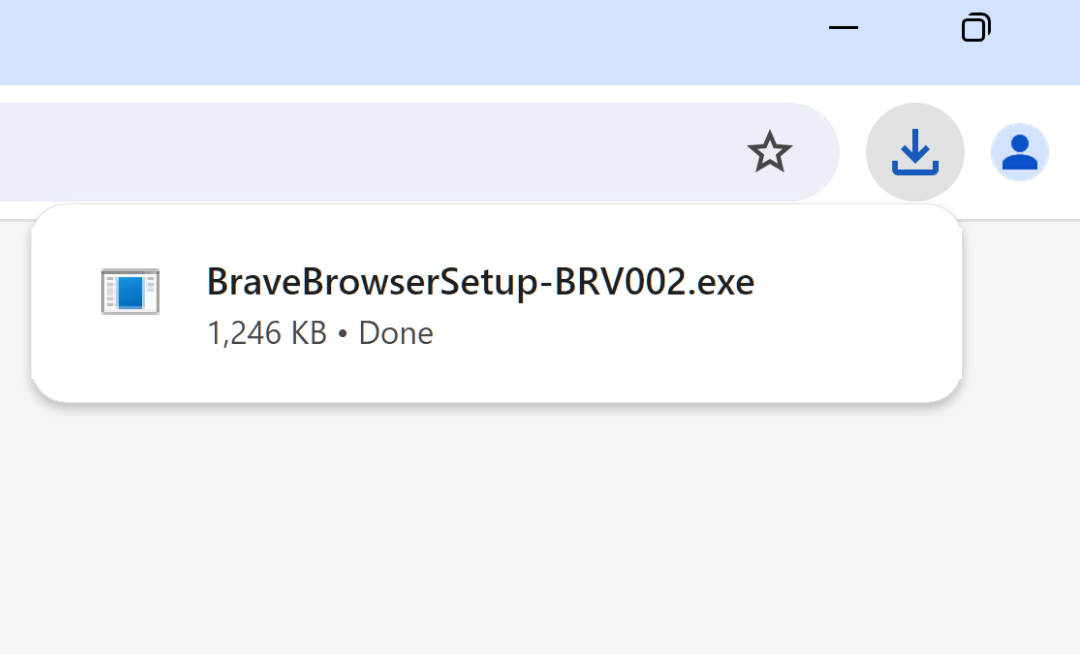

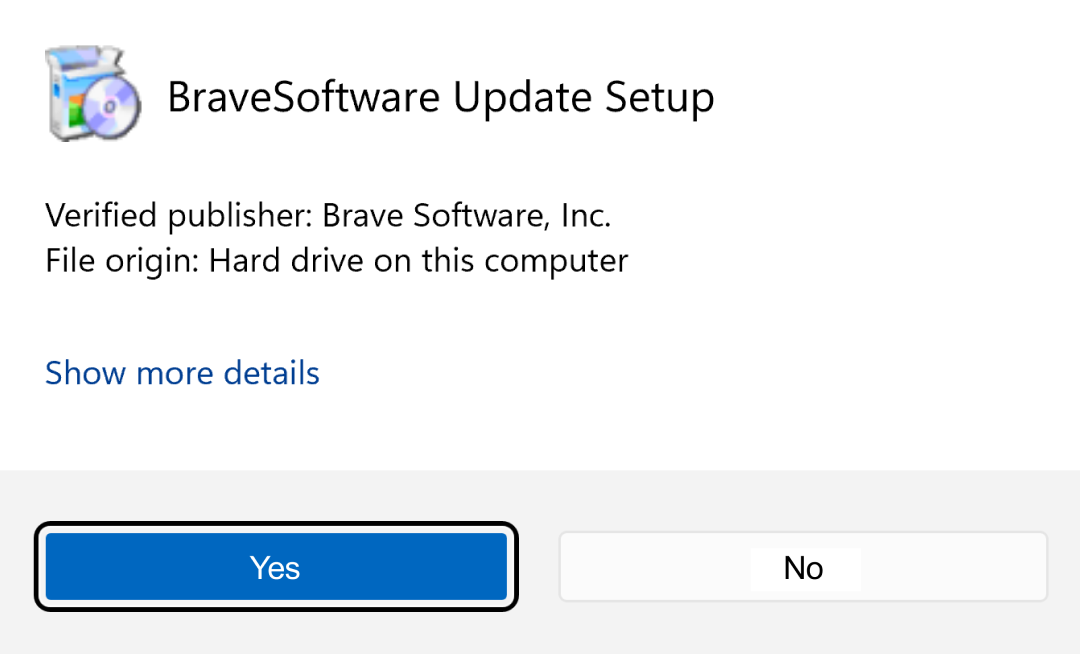

I represent Brave, a rapidly growing Internet browser based in San Francisco. Brave is at the cutting edge of the online industry. Its CEO, Brendan Eich, is the inventor of JavaScript, and co-founded Mozilla/Firefox. Brave is headquartered in San Francisco and innovates in areas such as private online advertising, machine learning, blockchain, and security.

I write to commend Californians for Consumer Privacy for your efforts to improve the privacy protections enjoyed by Californians thus far, and for launching this second ballot initiative. I also offer feedback on eight points in the draft text that may further improve the level of privacy protection it offers.

A second ballot initiative is necessary, as you write:

Even before the CCPA had gone into effect, however, businesses began to try to weaken the law. In the 2019-20 legislative session alone, members of the Legislature proposed more than a dozen bills to amend the CCPA, and it appears that business will continue to push for modifications that weaken the law.[1]

It is no surprise that 88% of Californians say they will vote in favor of your second ballot initiative, and that only 4% say they will vote to oppose it. Brave joins with Californians in supporting this measure.

This draft CPREA has the potential to apply the Fair Information Practice Principles, originally devised in the United States in 1973, for all Californians. This will be a significant advance. Brave believes these principles are essential, and commends the provisions for data minimization, purpose specification, security, transparency, accuracy, accountability in §3.

The draft CPREA also introduces a legal definition of “cross-context behavioral advertising” in §13(f). This is a critically important development, and recognizes the interests and importance of the direct relationship between publishers and their audiences.

I also write to highlight several points of concern in the draft text.

1. Personal information: The definition of “personal information” in §1798.140 (v) appears to be as broad as that in the GDPR, but with a proviso that it does not include publicly available information. In our view, the definition of personal information should be identical to the definition of “personal data” in EU data protection law, in the interest of interoperability.

AB-874, signed into law by Governor Newsom on 13 October, appears to provide a way forward. Per AB-874, personal information continues to not include “publicly available” information. The definition of publicly available in Governor Newsom’s proposed regulations is limited to “information that is lawfully made available from federal, state, or local government records.”[2] CPREA §1798.140 (v) (2) should adopt this definition.

2. Legal bases: We regret that CPREA does not require a legal basis as a condition for the processing of personal information. Brave’s view is that legal bases, such as consent, contract, and legitimate interest, would enhance the standard of privacy for Californians. Moreover, introducing the concept of a legal basis to CPREA would give effect to purpose specification.

Purpose specification, provided for in CPREA §3 (B) (2), has the potential to stop the internal data free-for-all within Big Tech companies, in which Californians’ personal information are used across purposes, and across lines of business, to create cascading monopolies. The current cross-use of data forecloses new entrants and limits innovation and choice in the market.[3]

3. The scope of a purpose: It is important to define the scope of a processing purpose, so that the boundaries between the permissible use of Californians’ personal information and other uses are easily understood. Omitting such a definition may render the concept of a purpose meaningless, because a business would be able to undermine a Californian’s privacy rights by framing their purposes in open-ended language at the time of collection, thereby side stepping the requirements you propose in several sections, for example in §1798.100 (a) (b) (c) (d) (e), and §1798.110 (a)(3), and (5), §1798.110(6)(c)(3), etc. In short, the lack of a defined scope of a purpose has the potential to undermine the objectives of CPREA.

We therefore urge you to consider remedying this omission. European regulators have grappled with the question of how the scope of a purpose should be defined, and determined that purposes must be specific enough to prevent “unanticipated use of personal data by the controller or by third parties and in loss of data subject control”.[4] Elsewhere, they note “if a purpose is sufficiently specific and clear, individuals will know what to expect: the way data are processed will be predictable”.[5] This is a sound basis for defining the scope of a purpose.

4. Notification: We are concerned that §4(b) may allow a third party to satisfy the requirement to notify simply by putting a notice on its own website, which may be a venue that no Californian ever visits.

5. Proportionality: We commend your provision in §13(d)(1)(A) and (B) that the requirements apply to businesses generating $25M+ revenue, or processing 100,000+ people’s data. This frees small businesses from regulatory burden. We suggest that CPREA should also take a risk based approach that targets big companies that create big risks with more aggressive scrutiny and enforcement. The Indian Data Protection Bill, for example, proposes the concept of “significant data fiduciaries” based on the volume and sensitivity of the personal data they process, financial turnover, risk of processing, novelty of the technology involved, and “any other factor relevant in causing harm to any data principal as a consequence of such processing”.[6] The entities are held to a higher standard of scrutiny and enforcement. The GDPR adopts a risk-based approach, incentivizing enforcers to focus their efforts on actors that create the most risk to the data rights of individuals, and relieving businesses that create little or no risk of greater regulatory burdens (such as the requirement for “prior engagement” with regulators, for example).

6. De-identification: We are concerned that §20(2) may provide for the gradual erosion of the standard of what “deidentified” means. We suggest that a provision be added to guarantee that any future standard is at least as robust as the standard it replaces.

13(k)(B) provides that a business commits to not “attempt[ing] to reidentify the information, except as necessary to ensure compliance with this subdivision”. This appears to mean that de-identified data be re-identified when required by a business, and may lower the standard of what deidentified is intended to mean.

7. Opt-out personal information as a privacy concern: §13(ad)(2)(b) exempts the sharing of personal information to communicate opt-outs from being covered by “sale”. We are concerned that this may not adequately protect Californians’ privacy. For example, acute privacy concerns arise from a system that operates by creating a unique identifier for every Californian and appending their individual opt-out choices to this identifier, and then circulating that identifier and choice, and updates to choices, among many disparate entities continuously.

8. Enforcement power: We suggest that the powers of the enforcer should not be limited to financial sanctions, but should also include the power to ban and verify the misuse of Californians’ personal information. Fines on their own appear to be ineffective.

Yours faithfully,

Dr Johnny Ryan FRHistS

Chief Policy & Industry Relations Officer

Notes

[1] Draft text of the CPREA ballot initiative, §2 (d).

[2] §1798.140 (O)(1)(K)(2).

[3] Brave to Federal Trade Commission, “Docket FTC-2018-0100: Hearing 6 on Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century”, 7 January 2019 (URL: /brave-ftc-jan-2019/).

[4] “Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679”, European Data Protection Board, 10 April 2018, p. 12.

[5] “Opinion 03/2013 on purpose limitation”, Article 29 Working Party, 2 April 2013, p. 13.

[6] Indian Data Protection Bill 2018, section 38 (1).