Partitioning network-state for privacy

This is the fourteenth post in an ongoing, regular series describing new and upcoming privacy features in Brave. This post describes work done by Software Engineer Aleksey Khoroshilov and Senior Software Engineer Ivan Efremov. We also thank the many members of the Chromium Team who have done enormous work on the network-state partitioning features described in this post. This post was written by Director of Privacy Peter Snyder.

The TL;DR

Brave now includes network-state partitioning features, protecting Brave users from an even greater range of online tracking techniques. Brave already includes the most aggressive strategy for partitioning DOM storage of any popular browser (giving Brave users extremely strong protections against the most common forms of online-tracking). Brave now provides comparable protections against less-common, more-sophisticated forms of tracking, ensuring Brave users have the best overall privacy protections available. These new features build on Brave’s many other powerful and novel protections, and ensure that Brave users benefit from the most robust and comprehensive privacy protections available in any popular browser.

We want to credit and appreciate the work the Chromium team has done building network-state partitioning features1. Most of Brave’s privacy protections come from developing privacy features beyond what is available in Chromium. Some of the features described in this post are different. Chromium engineers have already done an enormous amount of work building network-state partitioning features into Chromium, features that are present but not enabled in most Chromium-based browsers. Brave engineers have done significant work testing, deploying and extending these partitioning features, but we want to highlight and gratefully acknowledge the privacy-improving work already done by the Chromium team.

Partitioning for Privacy (or, for Every Site, a Sandbox)

When applied to Web browsers, “partitioning” is a category of technique for improving Web privacy. “Online tracking” broadly refers to companies trying to follow you across the Web, linking your behavior on different sites to create a profile about you and your interests. “Partitioning” defends against online tracking by putting each site in its own independent, isolated area, preventing what you do on one site from being linkable to what you do anywhere else.

Partitioning-based defenses are appealing because they (generally) provide strong privacy protections without breaking desirable page behaviors. A successful partitioning defense would allow your browser to load code and resources from online trackers without the tracker being able to identify you or follow you across sites.

To give a concrete example, partitioning defenses allow you to load a Facebook widget on cnn.com, and load the same Facebook widget on foxnews.com, but without Facebook learning that the same browser visited both CNN and Fox News. What happens on one site stays on that site. When partitioning is successful, a site (and third-parties running on that site) can learn what you do on that site, but not what you do anywhere else on the Web.

Partitioning strategies are appealing because they are general and platform-wide. This differs from other popular approaches, such as ad blocker-style filter lists which attempt to distinguish good code from bad code, and prevent the bad code from running. Identifying and blocking “bad” parties can be extremely useful, but comes with risks too: figuring out which code is “bad” can be extremely difficult, and blocking “bad” code can break websites, among other difficulties. Platform-wide approaches such as partitioning (and also Brave’s fingerprint-randomization techniques) provide the same protections against everything on the Web, “good” and “bad,” and so avoid many difficulties.2

Brave Already Partitions Cookies (Aggressively)

For the browser features mostly commonly used for tracking online, Brave uses the most aggressive, most-protective partitioning strategy of any popular browser. Most online trackers use third-party DOM storage, including cookies, localStorage, and other application-level APIs to identify you across the Web.

Brave protects users against most online tracking with a unique storage partitioning system called ephemeral third-party site storage. Similar to other privacy-focused browsers, Brave partitions third-party storage to prevent trackers from following you on the Web. Unique from all other browsers though, Brave automatically deletes any data that trackers set in your browser when you’re finished using a site, even though that data is partitioned. This gives Brave users extra protection, including against certain determined attackers3, and against specific forms of unintended data sharing between first and third parties4, among other threats.

| Browser | Partitions Third-Party Storage? | When is Storage Cleared? |

|---|---|---|

| Brave | Yes | When each site is closed. |

| Chrome | No | Never |

| Edge | No | Never |

| Firefox | Yes | Never 5 |

| Safari | Yes | When the browser is closed. |

| Tor Browser | Yes | When the browser is closed. |

The above table summarizes the state of DOM storage partitioning in current popular browsers. The next section presents Brave’s new partitioning features, and how they protect users against less-common, more sophisticated forms of tracking.

Brave Now Partitions Network State

In addition to Brave’s existing novel and aggressive DOM storage partitioning features, Brave now partitions a far wider range of storage and tracking mechanisms. Trackers mostly use traditional storage APIs to track users, partially because those APIs are easy to use, but also because the most popular browsers (Chrome and Edge) provide no significant protections against these common tracking techniques.

Sophisticated trackers, though, are increasingly moving to other tracking techniques to circumvent the DOM storage partitioning protections. In response, we at Brave (along with folks at other privacy-focused browsers) are responding to the trackers by deploying even more robust partitioning features.

Starting with browser releases in early 2022, Brave will partition other storage mechanisms in the browser, sometimes broadly referred to as “network state”. Previous partitioning features targeted the APIs websites are supposed to use to set application-level state for users (including setting identifiers); these new partitioning features cover a much wider range of browser features sites can abuse to track users on the Web, in ways not intended by the Web API or related browser standards.

Brave’s network state partitioning is a combination of a) enabling functionality available in Chromium (but disabled for most Chrome and Edge users) and b) new partitioning features developed at Brave, that we are working to upstream to benefit other Chromium browsers.

We encourage everyone interested in the state of partitioning-based browser features to visit the excellent privacytests.org project, which has a great comparison grid of the state of privacy features (partitioning based and otherwise) available in popular Web browsers.

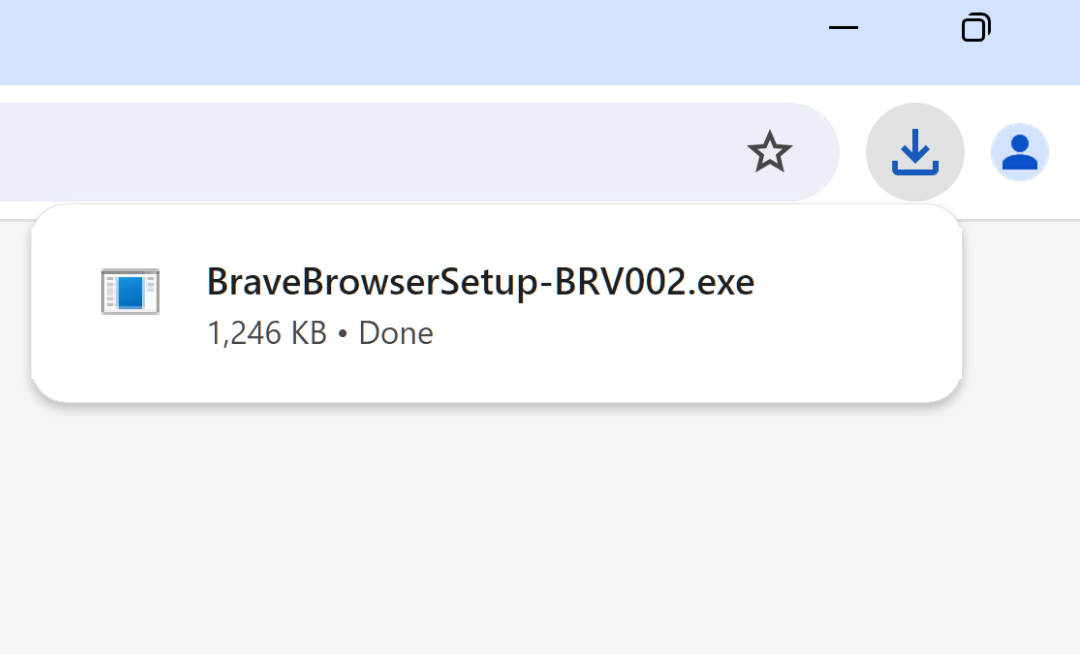

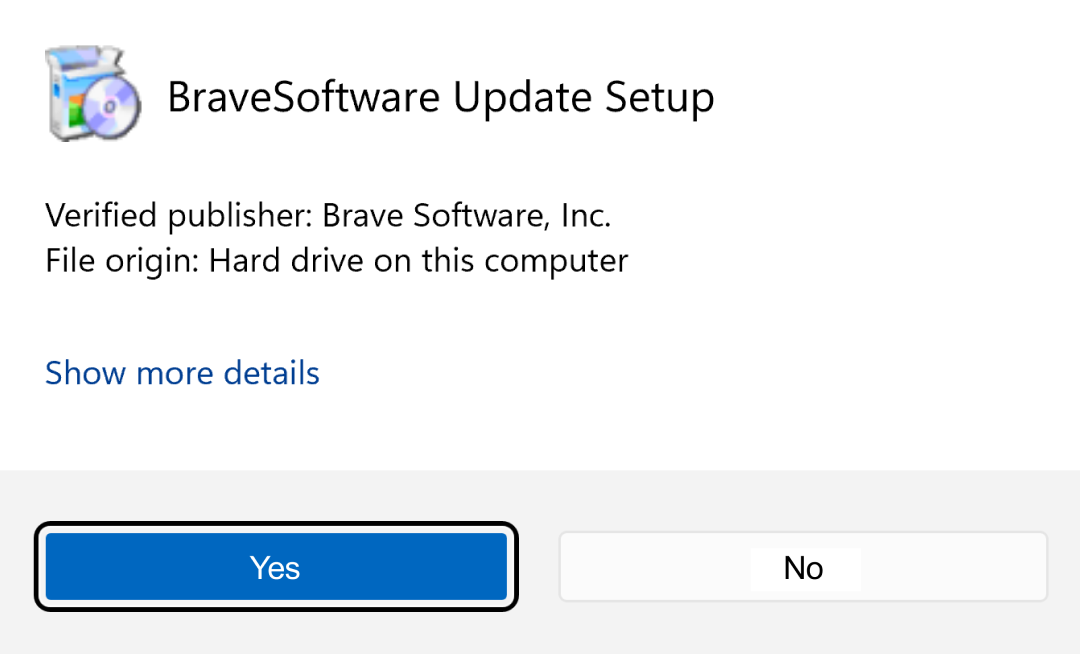

Brave 1.33

Brave 1.33

|

|

|---|---|

| State Partitioning Tests | |

| Alt-Svc | ✅ |

| Blob | ❌ |

| BrodcastChannel | ✅ |

| CacheStorage | ✅ |

| cookie | ✅ |

| CSS cache | ✅ |

| favicon cache | ✅ |

| fetch cache | ✅ |

| font cache | ✅ |

| H1 connection | ✅ |

| H2 connection | ✅ |

| H3 connection | ✅ |

| HSTS cache | ❌ |

| iframe cache | ✅ |

| image cache | ✅ |

| indexedDB | ✅ |

| localStorage | ✅ |

| locks | ✅ |

| prefetch cache | ✅ |

| ServiceWorker | ✅ |

| SharedWorker | ✅ |

| TLS Session ID | ✅ |

| Web SQL Database | ✅ |

| XMLHttpRequest cache | ✅ |

Partitioning: Necessary, but Not Sufficient, for Privacy

Brave has long provided the best protections against the most common forms of online tracking.

With the network-state partitioning features discussed in this post, Brave provides even better privacy protections for users; the strongest protections against DOM storage based tracking, and protections against network-state based tracking that are similar-to-or-exceed what’s available in any other popular browser. And for the very-small-and-shrinking number of network-state features not yet partitioned in Brave (i.e., partitioning HSTS instructions and certain kinds of blob values), we will work, internally and with upstream, to extend protections to these remaining features as well.

Even with these new network-state partitioning features, there is still much more work needed to build a Web that truly respects user privacy. For example, Brave recently documented a range of remaining, still-unpartitioned browser capabilities that can be abused to track users across the web. We presented these findings in a recent blog post and research paper, and are discussing possible solutions with other browser vendors.

Last, we emphasize that partitioning is a useful tool for protecting privacy, but it’s not sufficient on its own. True privacy protections must be applied in depth, in an unapologetically aggressive and user-first manner. What makes partitioning-based defenses appealing to browser vendors (that partitioning policies don’t require identifying bad actors, that they’re “neutral”, etc) is also what makes partitioning defenses inherently limited. Neutrality towards actors on the Web is an anti-goal. User-hostile, bad actors should be blocked, circumvented and defanged, even when those bad actions can’t be described (or proscribed) in general terms.

We’re excited about the network-state partitioning features described in this post, and that they’ll protect users from an even greater range of privacy threats. But, even more so, we’re excited to combine the new network-state partitioning features with our existing, best-in-industry privacy protections, giving Brave users the most user-first, privacy-respecting Web experience available today.