Cherishing the World of Analog, and Advocating For Your Right to Privacy

[00:00:00] Luke: From privacy concerns to limitless potential, AI is rapidly impacting our evolving society. In this new season of the Brave Technologist podcast, we’re demystifying artificial intelligence, challenging the status quo, and empowering everyday people to embrace the digital revolution. I’m your host, Luke Malks, VP of Business Operations at Brave Software, makers of the privacy respecting Brave browser and search engine, now powering AI with the Brave Search API.

[00:00:29] You’re listening to a new episode of the Brave Technologist. This one features Carissa Valise. Carissa is an associate professor in philosophy at the Institute for Ethics in AI at the University of Oxford. She’s a recipient of the 2021 Herbert A. Simon Award for Outstanding Research in Computing and Philosophy and the author of a highly acclaimed book, Privacy is Power.

[00:00:50] In this episode, we discussed why she advocates for an end to the data economy and the alternative models available, ways to be an advocate for privacy online, and the [00:01:00] specific tools you can make the switch to, different ways to design AI that would require less of our personal data, and how the future of the internet is still unwritten.

[00:01:07] Meaning we’ll have lots of time to change the course and improve the Internet as we go. And now, for this week’s episode of the Brave Technologist. Hi Carissa, welcome to the Brave Technologist podcast. How are you doing

[00:01:21] Carissa: today? Hi Luke, thanks for having me. I’m doing well, thanks. How are you doing?

[00:01:25] Luke: Doing great.

[00:01:26] We’re really glad to have you on. Just to kind of get things started, can you give our audience a little bit of background, like kind of how you ended up kind of doing what you’re doing? Was this always an interest of yours or was this something you kind of developed over time? Sure. I think I’ve

[00:01:38] Carissa: always been quite a private person.

[00:01:40] I think that’s kind of my personality that I’m probably more sensitive about privacy than the average person. And then I started researching the history of my family and I learned a lot that I didn’t know and that they hadn’t told me, which led me to wonder about the right to privacy. I found that there wasn’t a lot in philosophy and the little that there was wasn’t very [00:02:00] updated.

[00:02:00] And then it turns out that that same summer Snowden came out with his revelations that we were being mass surveilled. And so I decided to change the topic of my doctoral dissertation, which I was writing at Oxford, against the advice most people I knew. that privacy wasn’t a thing anymore, that it was history, that I wouldn’t have a career, that philosophy didn’t talk about it, that I should write about Aristotle.

[00:02:22] And I decided to change the topic of my dissertation and wrote my PhD thesis on the ethics of privacy and surveillance.

[00:02:29] Luke: That’s really interesting. Yeah. We’re glad you made that choice. I think, you know, and it’s funny too. I mean, like hearing you, say that feedback, it’s a lot of the things that I started hearing too, like I’m more on the business side when I was like, why are you going to work for a company that wants to work on privacy?

[00:02:42] No one cares about that. And then one of the great things now is just kind of looking back and saying, well, actually. Everybody that’s using this product cares in some form or fashion about it or, or about what you get from having privacy, right? And, or perhaps people that are picking up books about privacy, right?

[00:02:56] Like are making a statement of interest in learning more, right? Which kind of takes me to the [00:03:00] next question too. I think, you have a book called that privacy is power. And in the book, you argue that privacy is essential for, you know, freedom and democracy. Kind of in that context of power. Could you elaborate on how the erosion of privacy poses a real threat to these fundamental values?

[00:03:14] Carissa: Yeah, I think everyone who thought that privacy wasn’t important and that wasn’t a thing anymore was actually not understanding what privacy is all about because privacy protects us from possible abuses of power. And as long as institutions are institutions and people are people. there will always be the temptation to abuse power.

[00:03:32] It doesn’t matter where you live or when you live, it might be expressed in different ways, the risks might vary, but there are always risks of abuse of power. So for a long time we’ve known that there is a very close connection between knowledge and power. So the more somebody knows about you, the more vulnerable you are to them.

[00:03:50] And the converse is also true. The more power somebody has, the more knowledge they have, or the more access to knowledge. And it’s not only that if you have money and power, you can buy books [00:04:00] and you can buy access to knowledge, but it’s also that you get to decide what counts as knowledge. So a big tech company gets to decide how we’re categorized and how we are treated, even when those might be questionable or even wrong.

[00:04:15] And so what we’re seeing now is a huge asymmetry of power in which a few know a lot about us. We know very little about how they’re using our data and details about how they work and how to design algorithms and so on. Part of the challenge that we have ahead is to redress that asymmetry of power.

[00:04:35] On the one hand, by making sure that Companies and other institutions don’t know things that they shouldn’t know about us. And on the other hand, making sure that we know a lot more about how data is being collected and used.

[00:04:48] Luke: We often hear this argument of like, you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear.

[00:04:51] How do you typically kind of counter that perspective?

[00:04:54] Carissa: Yeah, well I think you have nothing to hide and nothing to fear as long as you are a [00:05:00] masochist, don’t care about your job prospects, the prospect of having a mortgage, and you don’t care about your family or friends, and you don’t care about democracy.

[00:05:11] If all of those are true, then you have nothing to hide and nothing to fear. But if one of them is not true, if you might ask for a job in the future or for a loan or any kind of other opportunity, including living in an apartment, if you don’t want to have your identity stolen, if you don’t want to lose money, if you don’t want to be publicly humiliated, if you want to keep your friends and family safe, if you want to have a democracy, then there are very good reasons to care about privacy because privacy.

[00:05:42] is the kind of key that opens the door to your, life. Of course, nobody would go out into the streets and make copies of their front key and just kind of dish them out to strangers. Because of course, most of those people are good people and they’re never going to hurt you. And they might even use that [00:06:00] key to do something nice for you.

[00:06:01] But eventually you will find someone who will abuse that power. And so privacy opens the door to To your worst drunken night, to the worst thing you’ve ever said, to the worst thing you’ve ever done, to all of your mistakes, and to that family member that you wish you didn’t have, or that photo that was taken out of context.

[00:06:21] Or just things like your credit card number. So, okay. You have nothing to hide. Give me your credit card number. Give me your password to your email. Most people don’t take me up on that offer.

[00:06:31] Luke: Yeah, definitely. When you see things like with how AI has been, there’s always this hype around AI, but then there’s the actual, like how it’s being used, how it could be used.

[00:06:41] How much does the proliferation and kind of more ubiquity with AI across the broader population concern you with regards to people’s privacy?

[00:06:49] Carissa: It concerns me a lot because the kind of AI that we’re using at the moment is a kind of AI that uses a lot of personal data and that might not be the case in the future.

[00:06:58] There are different ways to design AI [00:07:00] and we might see AIs that are more intelligent and therefore less need data, like human beings don’t need millions of examples of something to be able to recognize it as what it is. But at the moment, AI uses a lot of personal data and we are embedding it in more and more services.

[00:07:17] often without having the chance to opt out. And so there’s a lot of questions, for instance, about whether large language models like open AIs, chat GPT are complying with the GDPR, which is the European General Data Protection Regulation. Because people are supposed to have a right to know what data is being held on them.

[00:07:39] And OpenAI doesn’t seem to know what data they have on people. People are supposed to be able to ask for a copy of their data. OpenAI doesn’t seem to be able to offer that. People have a right to correct the data held on them. And as you know, these large language models create a lot of [00:08:00] fabrications, confabulations, they make up things.

[00:08:03] It’s not like we have the opportunity to correct it and make sure that they won’t make up other things about us. So there is a huge question mark there. And there are a lot of cases in courts right now.

[00:08:15] Luke: Yeah. And, and on that point too, I think, you mentioned GDPR and, you know, it’s been in the wild now for a few years.

[00:08:22] Looking at how this has played out, it’s European regulation, but it really kind of started to set us kind of an operating model for the broader world, right? How confident are you in the ability for regulation to actually handle this problem?

[00:08:35] Carissa: Of course, there are all kinds of barriers to good regulation, including whether the regulators understand these issues well enough.

[00:08:44] And in some cases, the answer has been clearly no. In other cases, it’s more complicated than that. I think, for instance, with the GDPR, I think regulators understood quite well what was at stake, but the pressures were too heavy to [00:09:00] get what they wanted. At the time, most people weren’t aware at all that there were privacy problems.

[00:09:05] it was very hard to do with so much industry pressure. So on the one hand, I am not optimistic if I only kind of base my response on what there is out there, but of course that would be very limited. I’m very optimistic in the sense that it’s perfectly possible to come up with good regulation.

[00:09:22] And I think, you know, the GDPR for all its faults has changed the public discourse around privacy around the world. It has changed the way companies. Think about data, the way they collect data, the way they make copies of the data and the way they communicate their practices to people. Now we have the DMA, which is the digital markets act in Europe, which will hopefully also go some way towards regulating these big companies, but at the same time.

[00:09:50] We still don’t see regulation of the kind that I would like to see. Like, for example, the most important thing that we should do is to ban the trade in personal data. It’s [00:10:00] basically too toxic for society to trade in personal data. Even in the most capitalist of societies, we agree that we don’t trade certain things.

[00:10:07] We don’t trade organs. We don’t trade the results of sports matches. We don’t trade boats. And for the same reason that we don’t buy or sell votes, we shouldn’t buy or sell personal data because at the end of the day, it gets used to much the same effect. That said, regulation is a very big part of the solution and maybe the most important part of the solution, but it’s not everything.

[00:10:29] There is also a big part to play in culture, in the way people demand better products for companies. And there is a huge market opportunity here for companies who build private. Privacy is a competitive advantage and it’s time for companies to see that. and you do see some examples of that. So I’m pretty optimistic that we will see more alternatives in the future.

[00:10:52] Luke: Yeah, that makes sense. So much of this like narrative around data as a new oil or whatever nonsense, right, when in reality, it’s like, there are better [00:11:00] ways that we can actually figure out, well, what do you actually need that data for? Can we find a better wrench or a better way to like do what the thing you need that data for and whatnot.

[00:11:08] Cause I think one thing that was great about GDPR was that it actually put words down as to like what personal data means. Whereas like how here in the U S it’s very much like privacy is very much seems to be defined by what big corporations say privacy means or how they market it. And so, no, I think that makes a lot of sense.

[00:11:23] Are you seeing alternative models out there to challenge the data economy that are interesting or concepts, anything that our listeners might find interesting to follow up on?

[00:11:32] Carissa: Sure. So we have examples like Signal, which you should use instead of WhatsApp. And Signal is currently a non for profit and it’s not a sustainable business model, but nonetheless, It’s very strong and it has done very well in both the design of the technology, but also getting picked up by more and more people.

[00:11:52] Another interesting example is DuckDuckGo. So DuckDuckGo is a search engine that doesn’t collect your [00:12:00] data and the way it works is through contextualized ads instead of personalized ads. So if you search for shoes, then you’ll get ads of shoes and, they don’t really need to know, you know, what your age is or whether you are one political party or another.

[00:12:15] And the way they earn their keep is when you click on that ad for shoes and you buy the shoes, They get money for you clicking on the ad and then they get a cut from your buying the shoes. So it’s a perfectly sustainable business model and it doesn’t need personal data. Another great example is Proton.

[00:12:36] ProtonMail has email, it has a VPN, it has a password manager, it has a drive, and all of their services are private. They, you can have a free account and then you have a limited, for instance, amount of storage space. And then if you want more, you can buy more [00:13:00] and they’re doing quite well there again. It’s a sustainable business model that also offers free products for those who want to try it or for those who don’t want the kind of upgrades that you can get when you pay.

[00:13:12] Luke: Do technology companies basically kind of have to be at the forefront of making this easier for users? Are you seeing things becoming more usable? It seems like kind of the regulators are, they have to see what’s on the table and if nobody’s building those things, right? There’s nothing to see.

[00:13:25] Where do you see this going over the next, you know, five years or so as AI kind of proliferates and there starts to be new demands around, well, we need to start verifying, you know, Actual people are posting things. And obviously like that seems to have some privacy implications too. Do you feel confident about technology being able to figure this out in a way that isn’t just going to expose us worse?

[00:13:48] There’s DNA services through corporations where you’re, you’re basically giving them your, your DNA and we’re seeing that used in ways by law enforcement that aren’t great, how confident are you in, technology actually being able to solve the [00:14:00] problem too, longterm, like over the next five years?

[00:14:03] Carissa: So I don’t feel confident about anything and whoever feels confident I think they are expressing kind of overconfidence because the future is not written.

[00:14:12] It depends on us and it depends on the kind of tech that people accept, the kind of tech that people demand, the kind of tech that people want to design. So it’s a kind of battle and I see trends that give us reason to be optimistic like these products that I’ve been talking to you about, you know, just five years ago they had a lot less.

[00:14:31] Market share than today, but of course there are also trends that are very, very worrying like AI using so much data. Like, yes, the pressure to have kind of systems that identify people as people, but you know, I think a lot of people are confident in one thing or another, but I would ask listeners to be very, very suspicious of anyone who says that they’re confident about something because they usually have a financial interest.

[00:14:56] So I’m just reading. One of these books by one of these tech bros, [00:15:00] and you know, they’re so confident about what’s the future of AI. And of course it just happens that if the future of AI is what they say they will be, they will become even more billionaires. What a coincidence, wouldn’t you know? So I will be very wary of talking like that and of kind of having people believe that kind of discourse.

[00:15:19] I think the future is unwritten. and that’s a great thing because it means that we still have a chance to think about how to design things and how to implement them and so on. But what I would like to see is. to have more of the onus on the designers of these systems and these systems than on human beings.

[00:15:35] So why is it that we need to prove that we are human beings? Why don’t we make the rules such that you can’t make an AI that pretends to be a human being? At the moment, it seems like the default is designing AIs To impersonate people. that is such a bizarre design decision that could be different.

[00:15:56] Luke: Makes a lot of sense. And I think it’s a really good point too, about being suspicious [00:16:00] because you’re absolutely right. Like there’s so much of what we see around privacy harm and implications of businesses and privacy is around these incentive models that are out there around data and like trying to how you see these things kind of play out in discourse around like things that are.

[00:16:17] Oh, well, people don’t care, you know, or whatever. And there’s always a motivation behind that. I think it’s a really great point that you made there. Aside from using tech that is privacy focused and be researching it like from what you’ve seen, what if somebody wanted to be more of an advocate for privacy, right?

[00:16:33] And have an impact, are there things that they could do that you would recommend?

[00:16:38] Carissa: So it depends on who you are and where you live and what your time commitment is and so on. It can be very, very simple or it can be more complicated. I have a whole chapter in the book about that. So I really recommend people to get Privacy is Power read it because You know, I could spend the whole hour just talking about the advice, but actually in the book it’s quite well organized and quite summarized and you have the right references so it’s [00:17:00] easier.

[00:17:00] But in general, I would advise to make an effort without making your life complicated. You don’t have to be perfect and it doesn’t have to be very complicated to make a very good change and a very kind of lasting and impactful change. One thing is to use Signal instead of WhatsApp, to use DuckDuckGo instead of Google search, to use ProtonMail instead of Gmail, to use ProtonDrive instead of Dropbox, and there is a very good website that is called PrivacyTools.

[00:17:31] io. in which you can look for alternatives to whatever product you might be wanting to use. Another advice is just to cherish the world of the analog and not neglect it in virtue of a virtual world that will always be lacking with respect to the analog world and that will tend to surveil you. So if you want a really good party, ask your friends not to take their phones out, not to take photos, not to upload anything.

[00:17:58] If you want to have a very good debate [00:18:00] with your students, turn the mics off and the cameras off. In general, use cash instead of electronic money. When you read a book in paper, nobody’s tracking you. Nobody knows what you’re reading. Nobody knows where you stop. Nobody knows what you’re highlighting, what catches your attention, how fast you read.

[00:18:21] Which is not the case if you read an electronic book, of course. And there’s just so many details like that, that I really recommend people to read the book.

[00:18:28] Luke: It’s wild too. I mean, when you think about all these ways that people are capturing data, like, almost like, and how much people don’t even realize.

[00:18:36] That it’s happening because just because it’s not happening in front of their face, right? I mean, it’s happened. The action is happening in front of their face, but the measurements not, you know, and that’s one thing like having worked on the advertising side that really blew my mind was, you know, just seeing the volume of network calls to happen when you load a website and how few of them are actually related to the content that you’re viewing.

[00:18:55] You know, and you realize that every single one of those things has bits of your information that are [00:19:00] going to companies you’ve never heard of, right? It’s, incredible how pervasive this stuff gets and how many different interests have these things. And even in the space don’t know where it ends up going, you know, as much as they like to act like they do.

[00:19:10] A different kind of question now. It’s I mean, like you put a ton of effort into your book and that’s like a monumentous effort on a topic like privacy, which is, it’s both fundamental and it’s also, it can be pretty broad to you, like in response to putting the book out there, have there been any like reactions that you didn’t expect or anticipate that you got from people that had read it?

[00:19:28] How has the reception been?

[00:19:30] Carissa: Yeah. So the reception has been more positive than I imagined. For instance, it was an economist book of the year. You know, the economist is a pretty. mainstream media. And I didn’t, they’re very much about, of course, the economy. you know, the fact that they found it interesting, this kind of proposal to end the trade in, personal data, it was surprising in, in a great way and quite kind of flattering.

[00:19:53] I’ve also had a lot of interest from policymakers. I’ve, you know, policymakers around the world have reached [00:20:00] out. From the U S to of course, the UK and Europe. And so it’s been a wonderful experience and yeah, I’m writing a new book, although I don’t really want to talk about it because it’s too early days, but I’m looking forward to that as well.

[00:20:12] And I just published an academic book called the ethics of privacy and surveillance, which actually doesn’t overlap with privacy is power and it’s more about. What exactly is the right to privacy and what exactly are our privacy related duties and things like the epistemology of privacy. So how much do you need to know about me for me to lose privacy to you?

[00:20:31] What if you think you know something, but it’s actually wrong? Or what if you know something and you’re very certain of it, but it’s actually Only partially true, or what if you have no good reason to think something, but you think something about me and it’s actually true. So all these kinds of fringe cases, which are very relevant because AI.

[00:20:52] Usually it’s probabilistic. And so when we know something, thanks to AI, it’s usually, we know it with a certain [00:21:00] degree of certainty.

[00:21:01] Luke: If this overlaps with the next book, then feel free to stop me on it. What areas are you kind of looking into now that are really interesting to you in this space?

[00:21:10] Carissa: Well, it’s a balance, you know, life is never simple, so it’s a balance between teaching and surviving and, uh, talking about these things and thinking new things. I’m veering more towards AI ethics and a, a bit away from privacy, even though I still think that privacy is the most important ethical problem when it comes to ai.

[00:21:31] Not only because it’s I important and, and, and kind of concerning in itself, but also because many of the problems that we tend to think about. Are related to AI actually stem from a privacy source that, you know, if we had privacy, we wouldn’t have those

[00:21:46] Luke: other problems. Makes sense. really like that you’re, you’re digging in on the ethics side too, because I think that that’s an area that just really gets ignored the ethics around like the need to collect all this data or the fact that it’s all just collected by default anyway is just [00:22:00] pretty, again, people really underestimate the scale that this is happening.

[00:22:04] It sounds hyperbolic, but it’s definitely unethical, like to be doing this to people at this scale, kind of wrapping it in this bow of convenience and whatnot. It’s, so I’m really glad you’re out there teaching this upcoming generation on this stuff because it’s super important. I mean, like even from the tech side, there are benefits that people get from using these products.

[00:22:21] I feel like there’s almost a generation that doesn’t realize that they have a right to privacy, whether it’s a natural right or written one. They almost feel like it’s just cool for them to do this. When you’re working with students, are they coming in with a good sense around what privacy is? Or, you know, is it something that once they learn about it, they’re basically like more on board with?

[00:22:42] it’s hard to tell because I haven’t, probably haven’t been teaching for long enough to really know how trends are changing, but I do see trends.

[00:22:51] Carissa: It’s just, they’re quite short lived. So like students three years ago seem to be very different from students today, but it’s also very possible that my [00:23:00] students are not good representatives of the whole of the population. So it’s hard to tell, but in general, I do find that young people. are just as worried about privacy as somebody like me.

[00:23:10] And it’s, I’m usually surprised that I don’t really have to convince them much why this is important. And it’s more a kind of way of unpacking why is it important exactly and what to do about it. But it depends also in the discipline. So when I teach people in ethics and philosophy, I think it’s easier.

[00:23:27] When I teach engineers, it’s a bit harder. There’s always one person in the room who really doesn’t see the point of privacy at all. And they tend to be quite similar in personality, you

[00:23:37] Luke: know. Yeah, that’s great. Any last impression you want to, leave our audience with? You know, or anything that we didn’t cover that you might want to get the point across on

[00:23:45] Carissa: before we wrap up?

[00:23:46] So maybe a couple of ideas. One of them you mentioned, but maybe it’s putting it another way, that a lot of people think it might be extreme or something like that to ban the trade in personal data. Yeah. But actually, when you think about it, [00:24:00] what’s crazy is to have a business model that depends on the systematic and mass violation of our right to privacy.

[00:24:06] And if we told people who lived in the 1940s about this, they would think we are absolutely out of our minds. So it really, it’s really that the tech companies have been so successful with their narrative that they’ve changed what is perceived to be normal, but this is not normal in any way. And the second idea is this thing about cherishing the analog world.

[00:24:29] When we translate the analog world into the digital, We essentially turned something that wasn’t data into data, into data that is trackable, taggable, and searchable. And we might not want to turn everything into digital. Partly because that’s a way to preserve privacy.

[00:24:48] Luke: Yeah, that’s great. If people want to follow what you’re doing or, look more into your work, where can they do

[00:24:53] Carissa: that?

[00:24:54] They can follow me on Twitter.

[00:24:57] Luke: You can say Twitter. We say Twitter here.[00:25:00]

[00:25:02] Carissa: They can follow me on LinkedIn as well. They can buy Privacy is Power and they can read the ethics of privacy and surveillance. Yes, those are the best, the best ways. Perfect.

[00:25:12] Luke: we’ll link those with the episode too so people can find them easily. Really appreciate you joining us today and sharing your insight in this.

[00:25:19] And, when the next book comes out, love to have you on to talk about that too.

[00:25:22] Carissa: Thank you so much. I really

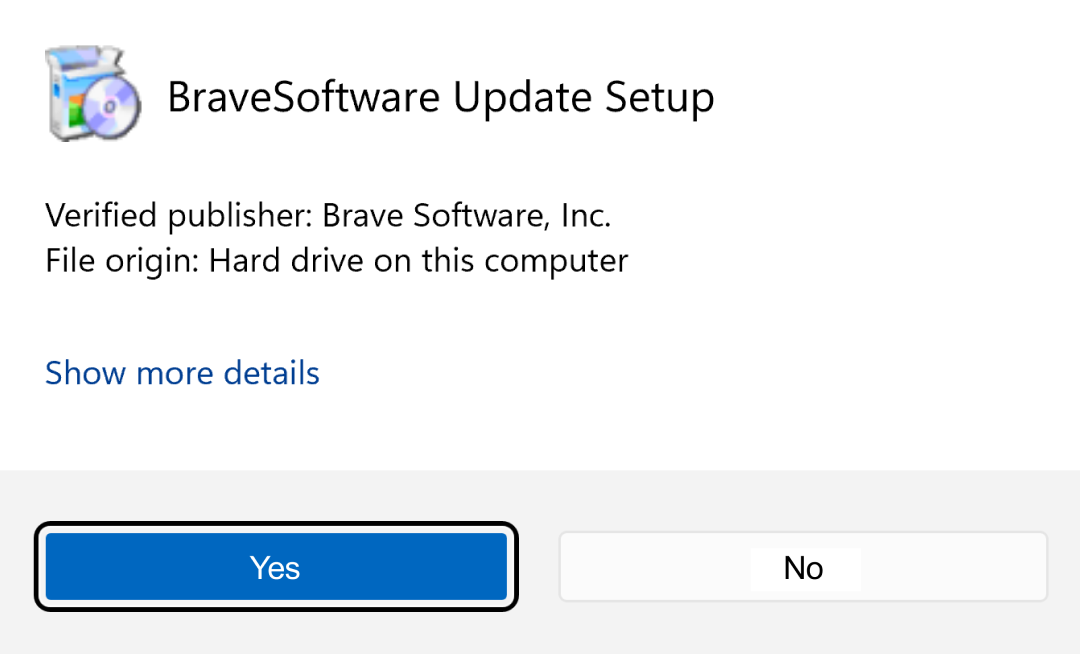

[00:25:24] Luke: appreciate that. Yeah. Have a good one. Thank you. You too. Thanks. Thanks for listening to the brave technologist podcast to never miss an episode. Make sure you hit follow in your podcast app. If you haven’t already made the switch to the brave browser, you can download it for free today at brave.

[00:25:39] com. And start using Brave Search, which enables you to search the web privately. Brave also shields you from the ads, trackers, and other creepy stuff following you across the web.