Google’s Topics API: Rebranding FLoC Without Addressing Key Privacy Issues

By Peter Snyder, Sr. Director of Privacy

Google recently announced the Topics API, a revision of the earlier FLoC API. Google claims this new API addresses FLoC’s serious privacy issues. Unfortunately, it does anything but. The Topics API only touches the smallest, most minor privacy issues in FLoC, while leaving its core intact. At issue is Google’s insistence on sharing information about people’s interests and behaviors with advertisers, trackers, and others on the Web that are hostile to privacy. These groups have no business—and no right—learning such sensitive information about you.

Briefly: FLoC vs. the Topics API

The Topics API is at root the same idea as FLoC. In both proposals the browser watches the sites you visit, uses that information to categorize your browsing interests, and then has your browser share that info back with advertisers, trackers, and the sites you visit—actors who otherwise wouldn’t know this data. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle of “learning” about you, all in the interest of selling more—and more targeted—advertising.

There are only two significant differences between FLoC and the the Topics API, neither of which do anything to address the core privacy harms:

First, in FLoC, the browser would broadcast all of your learned interests to any site that asked; what Chrome learned about you anywhere, was shared everywhere. The Topics API improves this slightly by letting an advertiser on Site A learn about your interests from site B, if and only if that advertiser was also present on Site B. But this does not qualify as a privacy improvement: the “fix” is merely addressing a privacy harm that FLoC itself introduced!

Second, in FLoC, your learned interests were stable across sites, making it slightly easier for sites to fingerprint you. The Topics API adds a small amount of randomness to your learned interests, to make this kind of fingerprinting-based re-identification more difficult. This is a useful improvement compared to FLoC, but only palliates a lesser flaw in FLoC. The most harmful issues remain. (Further, the enormous amount of fingerprinting surface already in Chrome, along with the fundamental problems in Google’s Privacy Budget proposal, mean that most Chrome users are already fingerprintable, Topics API or otherwise)

Google shouldn’t decide what you consider sensitive

The Topics API does not address the core harmfulness of FLoC: that it’s arrogant and dangerous for Google to be the arbiter of what users consider “sensitive” data.

Google says it will take care to share only “non-sensitive” interests with sites. But there is no such thing as categorically non-sensitive data; there is no data that’s always safe or respectful to share. Things that are safe to share about one person in one context, will be closely guarded secrets to another. Meaningful privacy is inherently specific to both context and person.

People should decide what they consider sensitive. Not Google.

For example, consider an interest like “job hunting.” Is this sensitive? Should it be protected? To a new college grad looking for their first job, maybe not. But what about for someone browsing their own employer’s website? Or consider an interest in “cheese and wine.” To you, it might be innocuous. But what about for people in certain religious or dietary communities?

As you can see, there’s no such thing as universally “sensitive” or “non-sensitive” information. For Google to presume otherwise—and to claim authority to make that decision for the user—is a clear violation of privacy.

Now, a defender of the Topics API might reply: “Users can opt-out of categories that are specifically sensitive to them.” Sure, this is technically feasible. But in practice, Google knows (as do all Big Tech companies) that defaults are rarely changed, and that users rarely even know they have the option to change. Google’s own employees often don’t understand the privacy settings in Google’s own software. Rather than see the Topics API as a solution to privacy harms, it’s more accurate to think of such controls as a way for Google to blame its victim for the harm Google does.

The Topics API favors monopolists like Google

In some ways, the Topics API is worse than FLoC. In FLoC, all advertisers would learn the same interests for each user. In the Topics API, an advertiser “only” learns user interests and behaviors for the pages on which that advertiser appears.

Since large advertisers (like Google) are included on most websites, they’ll be relatively unaffected by the Topics API change. But it will put small advertisers at a significant disadvantage. Smaller advertisers appear on far fewer sites, meaning that the Topics API essentially strengthens Google’s advertising monopoly by default. And it does so through the cynical guise of user privacy.

But remember: This isn’t a debate about whether “Topics API is better than FLoC,” or vice versa. Both hurt privacy and competition, and both are the direct result of Google’s continued pursuit: to siphon more data from users and share that data with advertisers, all without asking or benefiting the users they collect it from. Google wins if we get bogged down arguing the merits of one over the other; “choosing” the lesser of two evils is no choice at all.

The Topics API is privacy-improving only if you compare it against Chrome out of the box

As highlighted in our earlier piece about FLoC, both FLoC and the Topics API are unambiguously harmful. Both systems are designed to share information about you with advertisers and organizations that you don’t know, and that are outright hostile to Web users’ privacy, without active permission or consent.

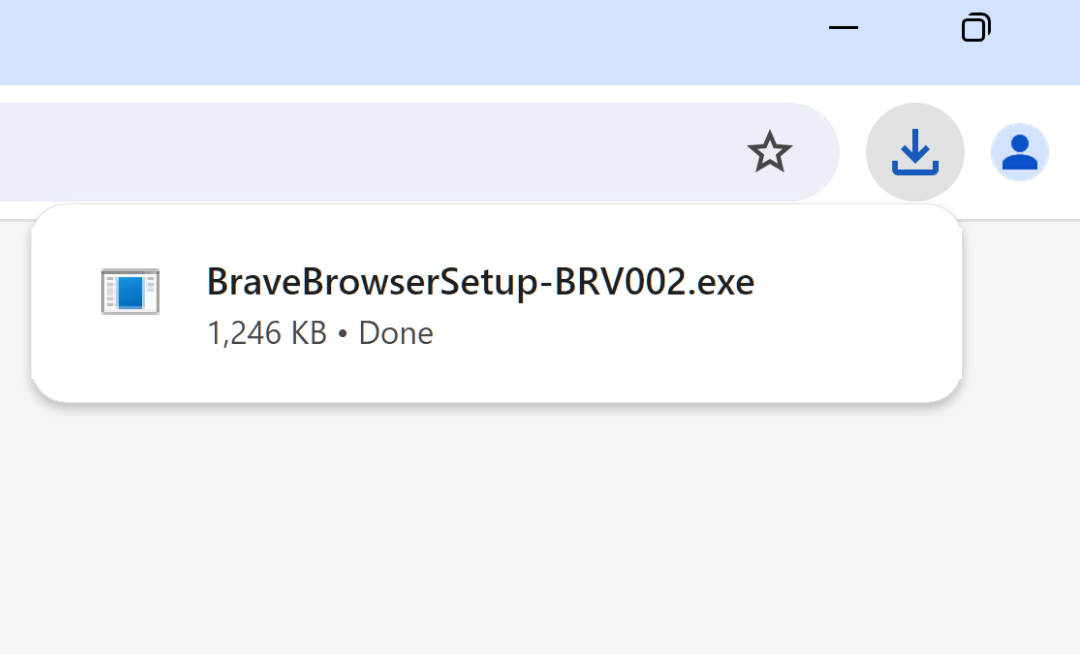

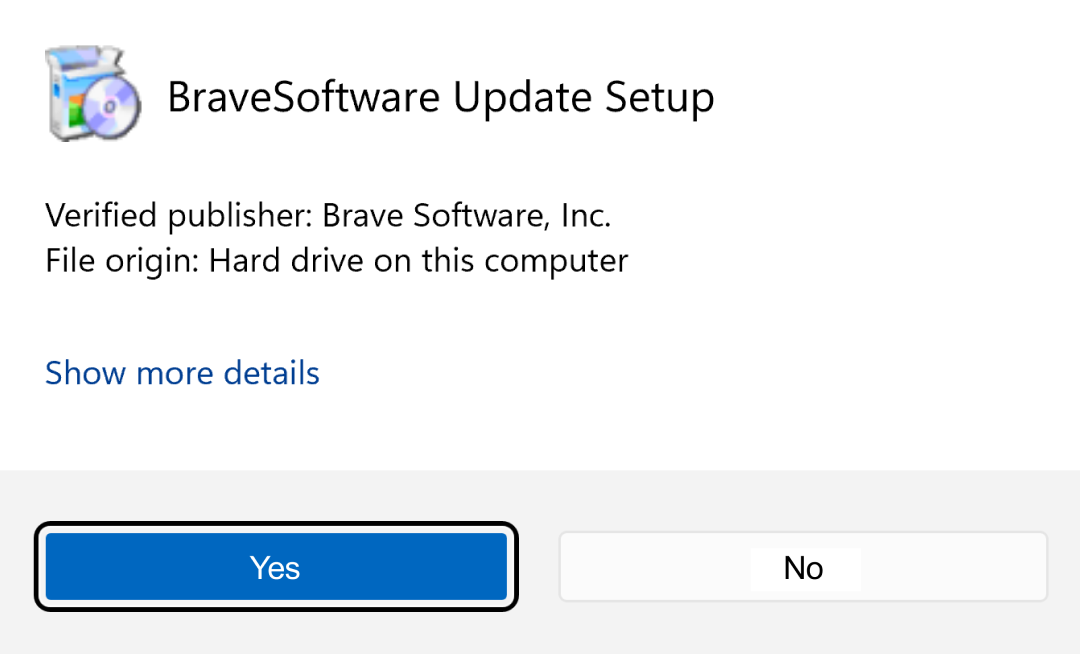

Google claims that these systems, along with its broader Privacy Sandbox proposal, improve privacy because they’re designed to replace third-party cookies. The plain truth is that privacy-respecting browsers like Brave (among others) have been protecting users against third-party tracking (via cookies or otherwise) for years now.

Google’s proposals are privacy-improving only from the cynical, self-serving baseline of “better than Google today.” Chrome is still the most privacy-harming popular browser on the market, and Google is trying to solve a problem they introduced by taking minor steps meant to consolidate their dominance on the ad tech landscape. Topics does not solve the core problem of Google broadcasting user data to sites, including potentially sensitive information.

FLoC, Privacy Sandbox, and the Topics API do not improve privacy; rather, they’re proposals to make the least private browser slightly less bad. They’re an incomplete and insufficient effort by Google to catch up with other browsers that offer real privacy protections (and that have done so for years).

Activists, researchers, and journalists should call a spade a spade. Google’s latest efforts are more of the same: a way to maintain their dominance of the Web (and Web advertising), while paying lip service to “protecting” the Open Web. The Web deserves far better protectors.