DNS

What is DNS?

The Domain Name System (DNS) is an Internet protocol that enables a browser and operating system to look up the IP addresses that correspond to domain names. IP addresses and domain names are each a type of identifier for devices on the Internet. IP addresses are numerical (like 203.0.113.43), while domain names are human-readable (like “example.com”). DNS is not a website, and you don’t need to interact with it directly when you’re using the Internet. Your browser and operating system handle it automatically.

Why is DNS necessary?

For one device to communicate with another over a network like the Internet, it needs the other device’s IP address. IP addresses are the only type of identifier that network infrastructure understands. However, people can’t easily remember IP addresses.

DNS is the solution. It allows people to use domain names instead, while their devices use DNS to look up the corresponding IP addresses.

The functionality of DNS is analogous to the contact list on your phone. You need someone’s phone number to call or text them, but phone numbers are hard to memorize. The contact list lets you store names and phone numbers together, and look up a name to find that person’s number.

How does DNS work?

When you visit a URL like example.com in your Web browser, your browser must first look up “example.com” in DNS to get the domain’s IP address. Then, the browser can contact the server at that IP address, asking it to send back the content of example.com’s website.

To do DNS lookups, your device must have the IP addresses of one or more DNS servers. When you connect your device to a network (like your home Internet, or public Wi-Fi) the network usually tells your device a DNS server’s address automatically. You can also manually specify which DNS servers your device uses, although you shouldn’t need to do so.

There’s no single entity in charge of maintaining DNS. Lots of different companies operate DNS servers, including ISPs, domain registrars (the companies that you can buy domain names from), and some large tech companies like Google.

What types of DNS records are there?

DNS holds a collection of “records,” each of which contains some information about a domain name. There are several different types of records.

- “A” records hold one or more IPv4 addresses that correspond to a domain name. If there are multiple IP addresses, any of them can be used. Putting multiple IP addresses in an A record is a common technique for “load balancing,” which spreads the work of hosting a website evenly across several different servers.

- “AAAA” records are like A records, but for IPv6 addresses instead of IPv4.

- “CNAME” records hold a domain name that corresponds to another domain name. For example, if a browser looks up “example.com”, it may get back a CNAME record that says “example.com maps to example.net”. In this case, it would then look up “example.net”. However, you would still see “example.com” in your browser’s address bar.

- “MX” records are for email. When you send an email, your email provider will look up the MX record for the domain that comes after the “@” in the destination email address. The MX record contains the IP address where email to that domain should be delivered.

There are lots of other record types, but the four listed above are the most common.

Is DNS susceptible to hacking?

When DNS was originally designed, the Internet didn’t have the same security threats we face today. As a result, DNS on its own doesn’t include ample security measures, and is vulnerable to manipulation or hacking. Terms for these kinds of DNS attacks include hijacking, spoofing, and cache poisoning.

Each of these methods redirect a user from the requested site to a site of the attacker’s choice. The goals of these attacks can be phishing, redirecting to serve ads or collect data, or even to censor content. Some common examples of redirection are:

- Registration or payment: You see this happen when you link to hotel Wi-Fi, try to visit example.com, and instead you’re redirected to the hotel’s webpage asking you to register or pay. Once you complete this sign-in process, you’re redirected back to the original, requested site. In this case the hotel Wi-Fi is intercepting your DNS request and replying with their own IP address rather than the IP address of the site you’re requesting.

- Censorship: A government or business can place their own DNS server on the network to control what citizens or employees get access to when they request a certain website. An example of this is the Great Firewall of China. If you’re on a network in China, you’re relying on China’s DNS table to return the requested IP address. When you request a censored site, you do not receive the correct IP address and thus do not get access to the requested site.

- Phishing: A hacker can, with stolen credentials, alter a DNS record to redirect users to a copycat site for phishing personal data and login information, or installing malware.

- Placing ads: ISPs can configure their local DNS table to send targeted ads to users.

Privacy concerns with DNS

In addition to security threats from the various methods of DNS redirection, there are also general issues regarding privacy and DNS. The DNS server your device uses can see which domain names your device is looking up, which gives it a lot of information about which websites you’re visiting. This can be a privacy concern if you don’t trust whoever is operating the DNS server, which is often your ISP. To mitigate this problem, you can configure your device to use an alternate DNS server, although you’d need to find a DNS provider you trust.

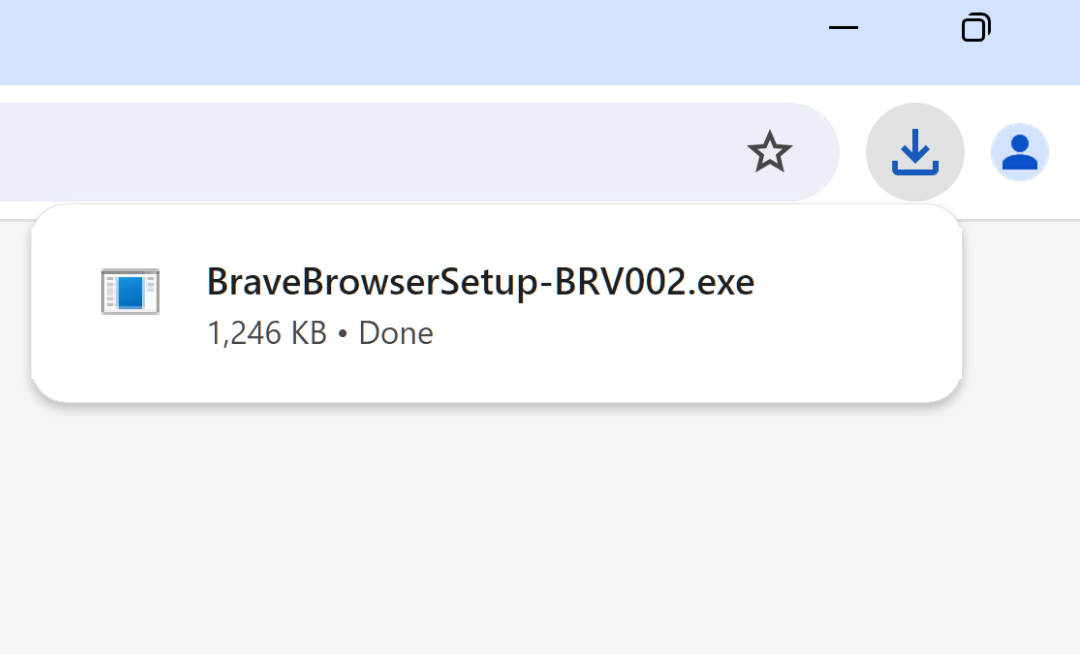

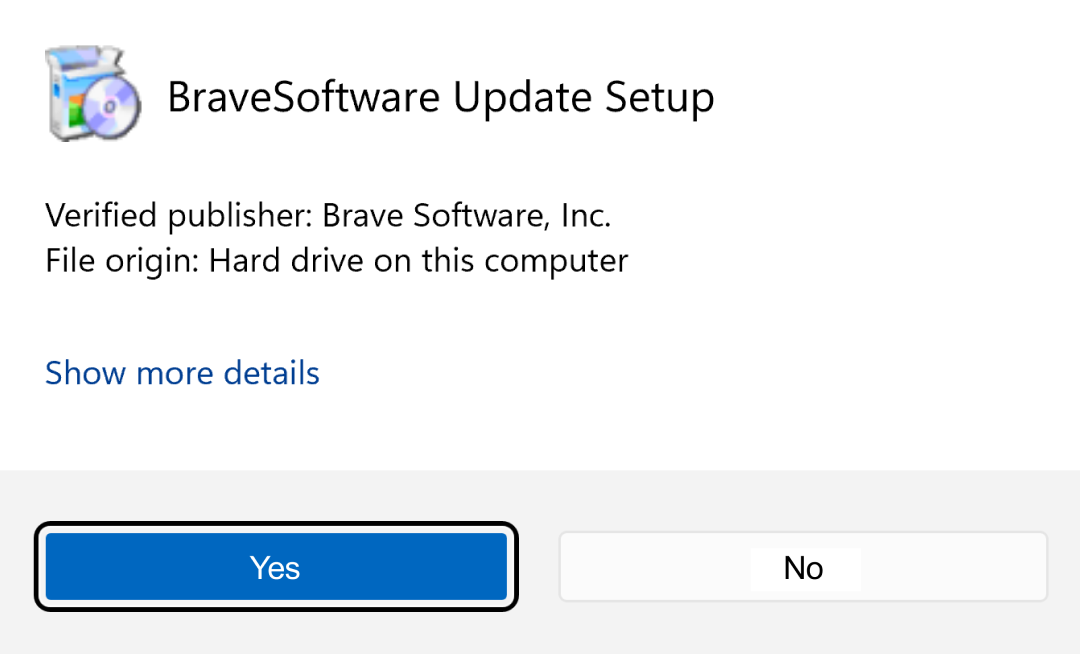

Another problem is that most DNS lookups are not encrypted, which means that if you’re on an unencrypted Wi-Fi network, anyone else on the network can see which domain names your device is looking up. One partial solution is called “DNS over HTTPS,” which uses encryption to protect DNS traffic. Most major browsers support it, including Brave, which calls the feature “secure DNS.” You can enable it in Brave’s settings. However, note that this will only protect DNS lookups that result from your Web browsing; DNS lookups from apps other than your browser may still be unencrypted.

Protections against DNS hacking

DNS attacks can be very hard to detect. Without protections built into DNS, it’s up to website owners and users to remain vigilant, and use available tools for protection.

Website owners can take several steps to protect their DNS table data against attacks, including:

- Use a protocol called DNSSEC (for Domain Name Server Security Extensions) to add a digital signature to a DNS table entry, verifying the record is authentic. This authentication step can help websites prevent their users from being routed to the wrong site.

- Monitor site traffic for sudden changes. If the number of visits drops suddenly or significantly, it may indicate that their DNS records have been hijacked in some way, and potential visitors are being rerouted.

- Periodically check DNS entries to make sure they haven’t been changed.

There are also things you can do to avoid being routed to the wrong website, and to protect yourself if you are connected to malicious content:

- Use a VPN, particularly when on a public Wi-Fi connection. This can protect against man-in-the-middle attacks that might attempt to intercept traffic between you and the DNS server.

- When a website loads, check that it’s the one you wanted. Even if it looks right, make sure the actual website address is correct (e.g. “example.com” and not “exampel.com”). Check the browser address bar for “https://” (not “http://”).

- Keep all software, including antivirus software, updated. This can help prevent malware from being installed if you end up at a malicious site.

- Use DoH (DNS over HTTPS) or DoT (DNS over TLS) to encrypt your DNS queries. The Brave browser has DoH capability, called “secure DNS,” built into its advanced security options (and may, depending on your ISP, enable this capability by default).

- If you don’t trust your ISP, and you can find an alternate DNS server you do trust, configure your device to use this alternate instead.

- Use the Brave browser—its enhanced ad blocking and tracker blocking capabilities provide added security against CNAME cloaking.