Why GDPR is Kryptonite to Google & Facebook on Anti-Trust

Brave’s submission to Margrethe Vestager, the EU Anti-Trust Chief, responding to her call for stakeholder input.

Brave’s recent submission to the European Competition Directorate General for Competition describes how a core principle of the GDPR called “purpose limitation” can be used to prevent anti-competitive behavior by Google and Facebook.

Commissioner Margrethe Vestager

European Commission

Rue de la Loi

1049 Brussels

Belgium

28 September 2018

Submission on shaping competition policy in the era of digitisation

Dear Commissioner Vestager,

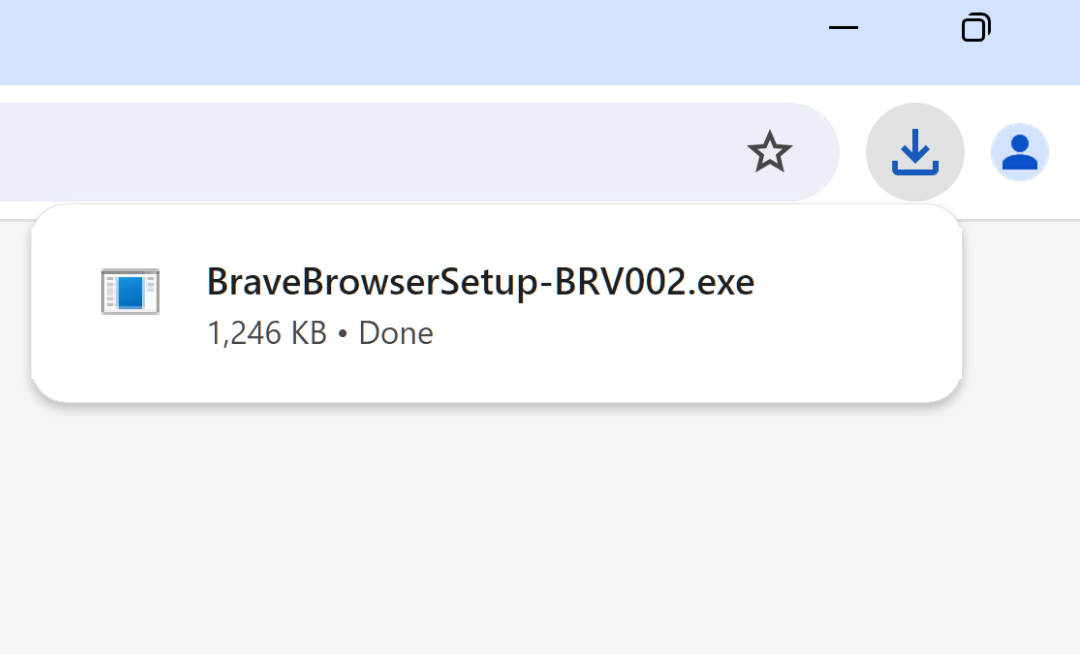

I represent Brave, a rapidly growing Internet browser with offices in San Francisco and London, and employees across Europe. Brave’s CEO, Brendan Eich, is the inventor of JavaScript, and co-founded Mozilla/Firefox.

The purpose of this submission to your consultation on “shaping competition policy in the era of digitisation” is to suggest an area of focus for panel 2: “Digital platforms’ market power”. This panel asks what can competition policy do to address leveraging and lock-in.

Where the processing of personal data confers competitive advantage, network effects in one business should not inevitably translate to network effects in another. Therefore, this submission suggests that the principle of “purpose limitation” in data protection law should be better leveraged to combat bundling, offensive leveraging, and other anti-competitive behaviour by dominant digital businesses.

Examples of how purpose limitation should curtail offensive leveraging by Google and Facebook are outlined in the middle part of this submission. The submission concludes with a proposal of two areas of work for the Commission’s consideration.

Purpose limitation

Purpose limitation is a core principle of data protection law. It is set out in Article 5 (b) of the GDPR as follows:

“Personal data shall be … collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes … (‘purpose limitation’)”

Purpose limitation is a well-established principle that dates back to the 1973 Council of Europe Resolution, the 1980 OECD “Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data”, and the 1981 Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data. It was also a principle of the 1995 Data Protection Directive.

This principle could be particularly effective in preventing offensive leveraging of data custody where “special categories of personal data” are concerned. These are data that reveal any of the following about a person:

“racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, or trade union membership, and the processing of genetic data, biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person, data concerning health or data concerning a natural person’s sex life or sexual orientation”.

These special categories of personal data enjoy particular protections in the GDPR, set out in Article 9. Unless the data have been made “manifestly public” by the person that they concern, the appropriate legal basis for processing those data is explicit consent.

Therefore, the purpose limitation principle protects a person’s opportunity to choose to opt-in to whatever particular service they decide, and forbids a company from automatically opt-ing a person in to all of its services where this entails data processing purposes that go beyond what the person has already opted-in to.

Provided that purpose limitation is enforced, it prevents dominant digital players from automatically leveraging personal data that they have collected for one purpose in one business in another business, to the disadvantage of competitors and new entrants.

Facebook

Article 6 (4) of the GDPR permits an opt-out (rather than opt-in) when the additional purpose that a company wants to process data for are “compatible” with the original purpose for which personal data were shared by users. Article 6 (4) d provides that one must consider “the possible consequences of the intended further processing for data subject”. This would be a serious impediment to Facebook, which is the subject of successive scandals that demonstrate harm to data subjects. Consider the following sample of Facebook crises:

- In October 2016 and December 2017, ProPublica revealed that Facebook could allow advertisers to exclude particular ethnicities1 and age categories2 from seeing their ads.

- In May 2017, a document leaked from Facebook in Australia that described its capacity to target teens at moments when they feel “worthless” or “insecure” for marketing purposes.3

- In September 2017, ProPublica revealed that it was possible to advertise to segments including “Jew haters”.4

- In March 2018, details about Cambridge Analytica scandal emerged.5

- In September 2018, the Communications Workers of America and the ACLU filed charges against Facebook with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for allowing recruiters to discriminate against women job seekers.6

Therefore, Facebook would have to seek consent for the various data processing purposes appropriate to its various business interests in order to comply with the purpose limitation principle. For example:

-

Facebook Audience Network requires the processing of personal data from Facebook users to target them on other websites. It seems unlikely that its purposes will be regarded as a compatible. People should have to be asked to opt-in to this business.

-

WhatsApp advertising should require users to give their consent (an opt-in, rather than an opt-out) for their personal data on WhatsApp to be processed for purposes unrelated to WhatsApp functionality on Facebook properties other than WhatsApp. People should have to be asked to opt-in to this business.

-

Facebook’s Newsfeed advertising should require consent, where the personal data concerned are “special category” data, unless these have been “manifestly made public by the data subject” – such as being marked “public” or visible to “friends of friends”.7 This includes all photos, videos, texts, etc. that reveal features such as ethnicity. People should have to be asked to opt-in to this business.

-

Facebook processes phone numbers submitted solely for a security purpose (two factor authentication) for other purposes related to its advertising business.8

Google

Google would have to seek consent for the various data processing purposes appropriate to its various business interests if it were to comply with the purpose limitation principle. For example, consider Google’s various advertising businesses:

- All personalised advertising9 on Google properties including Search, Youtube, Maps, and the websites where Google provides advertising should require that users opt-in. The services that should be affected include targeting features of AdWords such as

- “remarketing”,10

- “affinity audiences”,11

- “custom affinity audiences”,12

- “in-market audiences”,13

- “similar audiences”,14

- “demographic targeting”,15

- “Floodlight” cross-device tracking,16

- “Customer Match”, which targets users and similar users based on personal data contributed by an advertisers,17 (A prospect would have had to give their consent to the advertiser for this to occur), and

“Remarketing lists for search ads (RLSA)”.18

Some of these products may share common purposes, but people should have to be asked to opt-in to many separate processing purposes before Google can necessarily rely on all of these products.

-

“Location targeting”,19 and “location extensions”, technologies in Google Maps enable advertising to target users based on geographical proximity. This may not be accepted as a compatible purpose with the original purpose for which location data were shared by users. If so, people should have to be asked to opt-in to this business.

-

Google Marketing Platform (previously “DoubleClick”), is Google’s “programmatic” advertising business, which targets specific ads to specific individuals on websites. It should require multiple opt-ins, because it involves a large number of separate processing purposes. For example, this (click ‘learn more’) is a not-exhaustive list of purposes that are currently pursued by the industry (note that many are probably unlawful, and few are openly acknowledged).

Sample programmatic purposes

- To inform the agents of prospective advertisers that you are on visiting the web site, so that the website can solicit bids for the opportunity to show an ad to you.

- To combine your browsing habits with data they already have collected about you (and infer further insights about you) so that they can select relevant ads for you. These ads may be for products you have shown interest in previously. This profile may include your income bracket, age and gender, habits, social media influence, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, political leaning, etc.

- To use your browsing habits to build or improve a profile about you, in order to sell these data to partners for online marketing, credit scoring, insurance companies, background checking services, and law enforcement. This profile may include your income bracket, age and gender, habits, social media influence, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, political leaning, etc.

- To identify whether you are the kind of person that its advertising clients want to show ads to.

- To combine your browsing habits with data they already have collected about you (and infer further insights about you), to personalize the service or product that it offers you. This may include determining whether to offer you discounts. This profile may include your income bracket, age and gender, habits, social media influence, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, political leaning, etc.

- To monitor your behaviour on websites in order to determine if you have viewed or interacted with an ad.

- To determine whether you have purchased one of its products or services following your viewing of or interaction with an ad that it has paid for.

- To combine your browsing habits with data they already have collected about you (and infer further insights about you), to verify that you are human rather than a “bot” attempting to defraud advertisers. This profile may include your income bracket, age and gender, habits, social media influence, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, political leaning, etc.

- To record the number of times you have viewed each ad, to prevent a single ad being shown to you too frequently.

- To combine your browsing habits with data they already have collected about you (and infer further insights about you), to understand how you and people similar to you browse the web. This profile may include your income bracket, age and gender, habits, social media influence, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, political leaning, etc.

Purpose limitation requires that people should be asked to opt-in to each of these purposes, and may have to do so in multiple contexts, before Google can process personal data for this business.

If, however, users have manually chosen to “sign in” to Google Search or Chrome, Google may argue that the purpose of these technologies is “compatible” with purposes users agreed to, and hope to use an opt-out rather than an opt-in.

Google did not give users choice in this matter. It recently introduced a policy wherein users of Google Chrome are automatically signed in to all Google businesses.

Following a loud user outcry, Google announced a partial reversal the auto opt-in-to-everything policy on 26 September, announcing that the next Chrome update will give users an opt-out.20 However, for the reasons outlined above, this opt-out is hardly an adequate or lawful solution. Purpose limitation in this context should mean that Google can not leverage its dominant position in one business (such as Chrome) to leverage a person’s data in another business (such as Shopping).

Suggested areas of work

Purpose limitation has the potential to be a useful and proportionate tool to enhance data protection, and prevent undue cross-market dominance. There are two areas that merit attention if this potential is to be realised.

First, the individual purpose must be tightly defined, so that anti-competitive conflation of multiple purposes can be clearly identified and addressed.

What a “purpose” is has not yet been strictly defined. The definition is absent from the GDPR, and from the previous Data Protection Directive. In its 2013 opinion on “purpose limitation”, the Article 29 Working Party of Member State data protection authorities went some way toward a definition: a purpose must be “sufficiently defined to enable the implementation of any necessary data protection safeguards,” and must be “sufficiently unambiguous and clearly expressed”.21 The test for judging what a single purpose is appears to be (quoting the 2013 opinion):

“If a purpose is sufficiently specific and clear, individuals will know what to expect: the way data are processed will be predictable.”22

One reading of this is that a purpose must be describable to the extent that the processing undertaken for it would not surprise the person who gave consent for it.

The concern is that this may not be specific enough to clearly define where a single purpose begins and ends, or to protect against the conflation of separate purposes as one “catch-all” purpose.

Also worrying is that the 2013 opinion on purpose limitation observed that “It is generally possible to break a ‘purpose’ down into a number of sub-purposes” in example 11, on page 53 of that opinion. Without further guidance, this could provide a pretext for the hiding of various purposes under an umbrella when they should actually be presented clearly and in a granular way. This would risk unanticipated use of personal data by the controller or by third parties and in loss of data subject control.23

Second, the competition and data protection authorities should together consider whether there is adequate enforcement of the purpose limitation principle. Google and Facebook are prime candidates for enforcement, and should be unable to use the personal data they process for the purpose of providing their service for other purposes without user permission. But in reality, they do currently use a “service-wide” opt-in for almost everything. The implications of this extend to both data protection and competition, and are matters for cooperation between competent authorities.

Request

As Joseph Stiglitz observed during the Federal Trade Commission’s hearings on competition and consumer protection last week:

“there have been innovations in anti-competitive practices. It may not be showing up in GDP. But it’s showing up in market power”.

For example, Google and Facebook today enjoy concentrated data power, and exploit their position to engage in offensive leveraging. It is likely that their so far uninterrupted success doing so will become a model to be emulated.

There are tools in data protection law that can be refined and applied to correct this. Therefore, the Commission is invited to consider these two areas of work, and the merit of using purpose limitation as a means to curb platform leveraging concerns.

We would be delighted to contribute to the conference on these matters, and to provide our insight into the online media and advertising sector.

Sincerely,

Dr Johnny Ryan FRHistS

Chief Policy & Industry Relations Officer

Brave