Brave answers US Senators questions on privacy and antitrust

Brave answers Senators Whitehouse, Booker, Graham and Leahy’s questions for the record from the US Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on privacy and anti-trust.

Senators Whitehouse, Booker, Graham and Leahy asked Brave to respond to questions for the record following last month’s US Senate Judiciary Committee hearing. Here are our answers.

The senators asked us about anti-trust and privacy problems in the digital advertising market. The answers below cover deceptive consent design, undue cost for publishers from “adtech tax”, theft from advertisers through “ad fraud”, and harm to the public. You can also watch the hearing and read Brave’s testimony here.

Senators’ questions:

I. Questions from Senator Whitehouse

II. Questions from Senator Booker

III. Questions from Senator Graham

IV. Questions from Senator Leahy

Questions submitted on May 28, 2019. Responses submitted on Responded June 12, 2019.

I. Questions from Senator Whitehouse

1. As we consider federal legislation regulating online data collection, data privacy, and data security, what are the most exploitative practices used to coerce consumers into granting consent that federal law should prohibit?

The IAB, a tracking industry trade body, promotes a “consent” design that incorporates common exploitative practices and “dark pattern” designs. It is called the “IAB transparency and consent framework”. This framework has proliferated to virtually every major website in the European Union since the application of the GDPR in May 2018, and is now a de facto standard – although an unlawful one. There are several problems worth highlighting.

First, and perhaps most pernicious, is that despite appearances, it does not necessarily matter what a person clicks on when shown one of the industry’s “consent notices”, because there are no technical security measures that prevent companies names in the IAB framework’s notices from sharing the data with their business partners. As the IAB acknowledged in a letter to the European Commission, the “real-time bidding” (RTB) advertising technology that this consent framework is often used for cannot legally use consent as a legal basis under the GDPR for precisely this reason:

“Consent under the GDPR must be ‘informed’, that is, the user consenting to the processing must have prior information as to the identity of the data controller processing his or her personal data and the purposes of the processing. As it is technically impossible for the user to have prior information about every data controller involved in a real-time (RTB) scenario, [it] … would seem, at least prima facie, to be incompatible with consent under the GDPR”.1

Despite this, the framework was launched in April 2018. Only one month later publishers forced the IAB to acknowledge again that that “there is no technical way to limit the way data is used after the data is received by a vendor for … [RTB] bidding”.2

This lack of control infringes Article 5 (1) f of the GDPR, which requires that personal data be kept secure and protected from unauthorized access and accidental disclosure. In other words, both before and after the launch of its consent framework, the IAB acknowledged that RTB data processing infringes the GDPR, irrespective of whether consent is sought. The IAB consent framework is a false legal veneer on top of unlawful data processing, and does not give people control, transparency, or accountability.

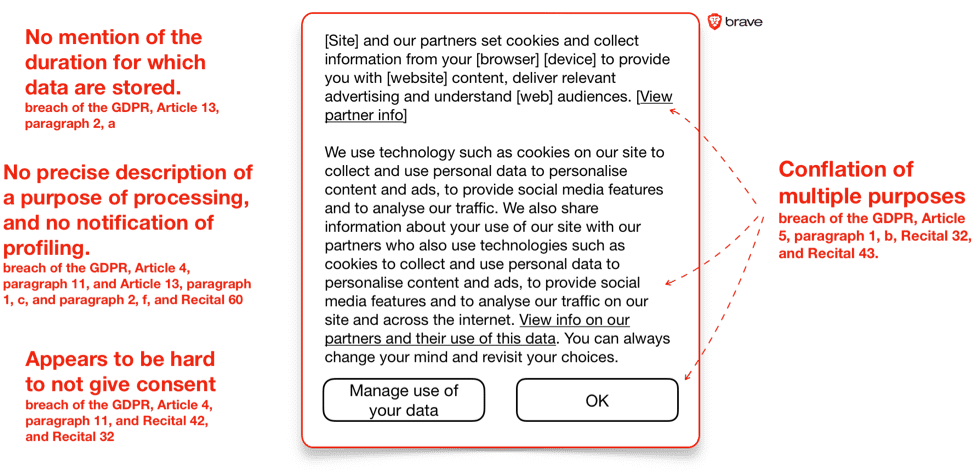

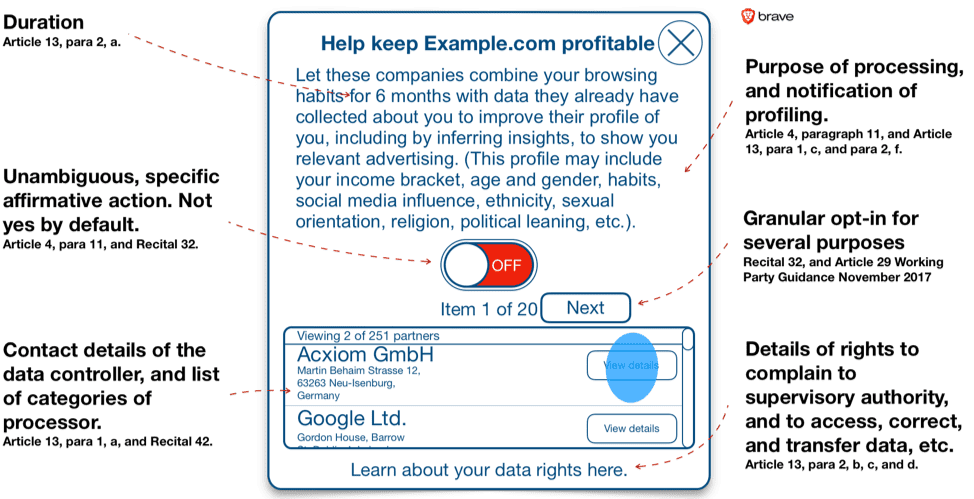

Second, as the diagram below summarizes, the framework fails to provide adequate information (infringing GDPR Article 5 and Article 13) and choice (GDPR Article 6 and Article 7).

Not GDPR compliant (IAB Framework)

First, Article 5 requires that consent be requested in a granular manner for “specified, explicit” purposes.3 Instead, IAB Europe’s proposed design bundles together a host of separate data processing purposes under a single “OK”/“Accept all” button. A user must click the “Manage use of your Data” button in order to view four (or ten, in the latest proposal)4 slightly less general opt-ins, and the companies5 requesting consent.

These opt-ins also appear to breach Article 5, because they too conflate multiple data processing purposes into a very small number of ill-defined consent requests. For example, a large array of separate ad tech consent requests6 are bundled together in a single “advertising personalization” opt-in.7 European regulators explicitly warned against conflating purposes:

“If the controller has conflated several purposes for processing and has not attempted to seek separate consent for each purpose, there is a lack of freedom. This granularity is closely related to the need of consent to be specific …. When data processing is done in pursuit of several purposes, the solution to comply with the conditions for valid consent lies in granularity, i.e. the separation of these purposes and obtaining consent for each purpose."8

Second, the text that IAB Europe proposes publishers display for the “advertising personalization” opt-in appears to severely breach of Article 69 and Article 1310 of the GDPR. In a single 49 word sentence, the text conflates several distinct purposes, and gives virtually no indication of what will be done with the reader’s personal data.

“Advertising personalization allow processing of a user’s data to provide and inform personalized advertising (including delivery, measurement, and reporting) based on a user’s preferences or interests known or inferred from data collected across multiple sites, apps, or devices; and/or accessing or storing information on devices for that purpose."11

Indeed, the latest revision to the IAB framework proposes text that summarizes the already inadequate 49 word sentence into an even briefer 13 words:

“Personalised ads can be shown to you based on a profile about you”.12

The updated list of purposes also includes matching of offline and online data, which is misleadingly described as:

“Data from offline data sources can be combined with your online activity in support of one or more purposes”.13

These notices fail to disclose that hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of companies will be sent your personal data. Nor does it say that some of these companies will combine these with a profile they already have built about you. Nor are you told that this profile includes things like your income bracket, age and gender, habits, social media influence, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, political leaning, etc. Nor do you know whether or not some of these companies will sell their data about you to other companies, perhaps for online marketing, credit scoring, insurance companies, background checking services, and law enforcement.

Third, a person is expected to say yes or no to all of the companies listed as data controllers14 (the latest revision does provide the means for a user to find and switch off specific companies).15 Since one should not be expected to trust all controllers equally, and since it is unlikely that all controllers apply equal safeguards of personal data, we suspect that this “take it or leave it” choice will not satisfy regulatory authorities.

Fourth, there is often to be no way to easily refuse to opt-in to the consent request that IAB Europe proposes, which also infringes the GDPR.16 Indeed, IAB Europe is in fact infringing Article 4 (11) on its own website, using an unlawful “cookie wall” that compels visits to accept tracking by Google, Facebook, and others, which may then monitor them.17

IAB Europe has widely promoted the notion that access to a website or app can be made conditional on consent for data processing that is not necessary for the requested service to be delivered, despite the clear requirements of the GDPR, and statements from several national data protection authorities, that say otherwise. Fortunately, this unlawful practice will shortly be under review, because of our formal complaint to the Irish Data Protection Commission.18

The IAB Europe notice copied below is a useful example of misleading consent design. It does not provide information about what data are collected for what purpose, and what legal basis is relied on for that purpose. IAB Europe’s policy notice says “we may rely on one or more of the following legal bases, depending on the circumstances”. It is therefore not possible to for a visitor to the website to know what legal basis is used for what purpose. Nor does IAB Europe provide information about which data are collected for what specific purpose.

Unlawful under the GDPR: IAB Europe “cookie wall”

Additional reading: particularly useful on Google and Facebook’s misleading consent design is “Deceived by design: How tech companies use dark patterns to discourage us from exercising our rights to privacy”. This report was produced by Forbrukerradet, the Norwegian Government’s consumer organization.

2. Are there best practices with respect to customer consent that we use should to model federal legislation?

The GDPR provides a useful model for consent, and this model should not be judged on the basis of the unlawful consent notices deployed by the IAB, Google, Facebook and others in defiance of clear guidance from data protection regulators. The GDPR’s consent have not yet been enforced in Europe, and as outlined above, the industry standard approaches infringe the Regulation in several important respects.

The GDPR’s consent requirements are sensible: clear information must be provided so that the parties involved can be held accountable.19 The notice must be specific to a specific processing purpose.20 The consent should not be automatic, and pre-ticked boxes are not allowed.21 The language and presentation of the request must be simple and clear, ideally the result of user testing.22 In addition, the GDPR requires that consent should be as easy to withdraw as it was to give.23 This means that companies that insist on harassing users with dozens of opt-in requests will have to remind users dozens of times that they can easily withdraw consent.

The problem is that these sensible rules have not been enforced, and that the IAB, Google, and Facebook have yet to comply. However, once the GDPR’s consent rules are enforced it will be counterproductive to harass users with unreasonable requests to agree to invasive data processing.

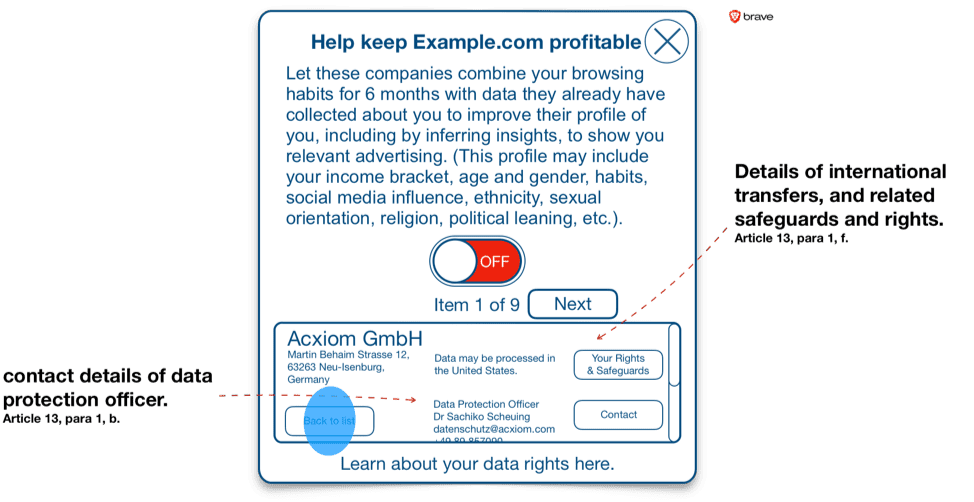

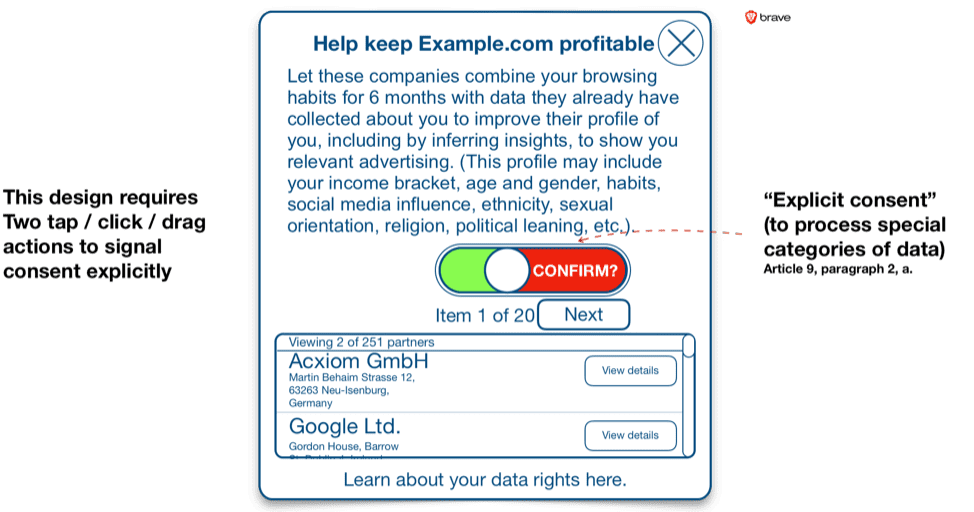

A consent request for a single purpose, on behalf of many controllers, might look like this (my design).

Proposed consent design

European data protection authorities suggest that consent notices should have layers of information so that they do not overload viewers with information, but make necessary details easily available.24 While some details, such as contact details for a company’s data protection officer, can be placed in a secondary layer, the primary layer must include “all basic details of the controller and the data processing activities envisaged”.25 The design proposed above follows the recommendations of the European data protection authorities.

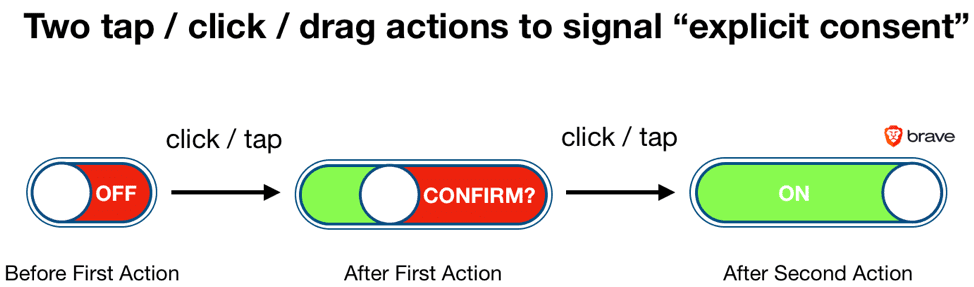

In addition to providing adequate information, consent must also allow for certainty on the part of the user and the parties receiving consent. Where data processing involves special category data, or will produce special category by inference, the processing requires “explicit consent”.26 To make consent explicit requires more confirmation. European data protection authorities suggest that two-stage verification is appropriate.27 One possible way to do this is set out below in my “two tap/click” action.

One can confirm one’s opt-in in a second movement of the finger, or cursor and click. It is unlikely that a person could confirm using this interface unless it was their intention.

II. Questions from Senator Booker

1. The German Bundeskartellamt now prohibits Facebook from combining data gathered from WhatsApp or Instagram and assigning those data to a Facebook user account without a user’s voluntary consent. Is this the most effective remedy available to address consolidation in the advertising technology market?

This is a useful first step, but as I testified, the issue is not limited to the sharing of data between subsidiaries, but across “data processing purposes”. Today, big tech companies create cascading monopolies not only by merging data between separate business entities that they own, such as WhatsApp and Facebook, but also by leveraging users’ data from one line of business to dominate other lines of business within a single entity too. This hurts nascent competitors, stifles innovation and reduces consumer choice.

The cross-use of data across purposes, and between different lines of business, can be analogous to the tying of two products. Indeed, tying and cross-use of data can occur at the same time, as Google Chrome’s latest “auto sign in to everything” controversy illustrates.28

Competition authorities in other jurisdictions have addressed this matter. As early as 2010, France’s Autorité de la concurrence highlighted the topic (in Opinion 10-A-13 on the cross-usage of customer databases). In 2015, Belgium’s regulator fined the Belgian National Lottery for reusing personal information acquired through its monopoly for a different, and incompatible, line of business.

If the GDPR principle of purpose limitation is enforced, then dominant companies would not be able to stifle competition by acquiring nascent and potential competitors. This is because the acquired firms’ data could no longer be blended with data held by acquirers for diverse processing purposes.

Article 5(1)(b), is the “purpose limitation” principle,29 which ring fences personal data held by companies so they can’t use it outside of consumer expectations. They need a legal basis for each data processing purpose.30

The “purpose limitation principle”, plus the ease of withdrawal of consent, enable freedom. Freedom for the market of users to softly “break up” – and “un-break up” – big tech companies by deciding what personal data can be used for. This will be possible if European regulators act against unlawful conflation of purposes that should be separate, and thereby force incumbents to compete in each new line of business on the merits alone, rather than on the basis of leveraged data accrued by virtue of their dominance in other lines of business.

a. Does this one decision in Europe open opportunities for new entrants into the market? Or are the major platforms still too large to compete with?

Brave does not compete with Facebook, WhatsApp, or Instagram for users. However, as a general point, the problem of cascading monopolies is a real one, and purpose limitation should be enforced to create a level playing field for all companies, and to empower users with the freedom to decide what services they choose to reward with their data.

2. The Microsoft, IBM, and AT&T antitrust cases each took the better part of a decade and were prohibitively expensive. However, Professor Tim Wu of Columbia Law School has argued that the IBM case was worth bringing because—despite the costs and delays—the litigation immediately caused IBM to change some of its anticompetitive conduct.i Others have made similar claims about Microsoft.ii

Do you believe that society and industry can benefit from enforcement agencies simply commencing antitrust litigation?

Brave does not have a corporate view on this specific question.

3. Apple dominates podcast listening via its podcast app. However, because of Apple’s privacy policies, podcast advertisers complain that they receive almost no data from Apple beyond anonymized user statistics. For example, a brand purchasing a web ad can tell how many people viewed it, how many people clicked on it, and, with cookies, possibly how many people visited the website without clicking through. However, generally speaking, when a brand purchases a podcast ad, they cannot even be certain about how many people listened to the ad.

We do not have any insight in to the podcast market. We do however have a view on the problems with reporting received by advertisers from other forms of digital advertising.

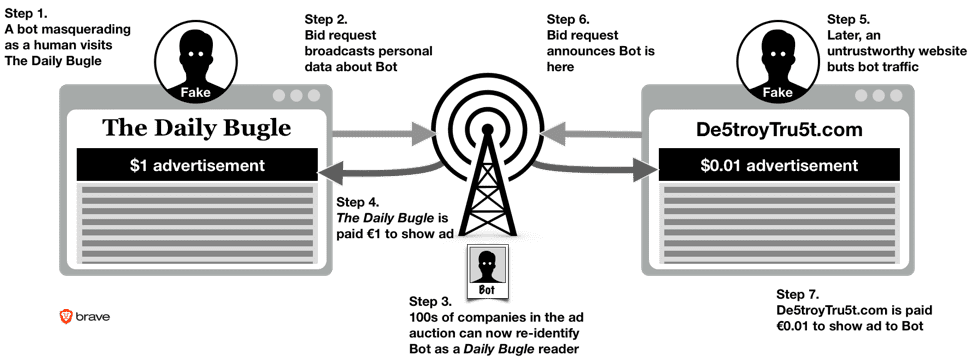

An advertiser does not know whether a viewer of an ad that it paid for is a human or a software “bot” masquerading as a person to fraudulently extract money from the advertiser. The Senator notes this point, citing Juniper Research’s 2018 estimate in question 4, below. It is worth noting that this estimate doubled in 2019, to $42 billion.

Fraud problems occur on Facebook too: it removed 1.3 billion fake accounts in the first half of 2018, and a further 3 billion fake accounts between late 2018 and early 2019.31 The scale of this problem is evident when one considers that only 2.4 billion users (real or fake) are on Facebook in a typical month.

The fraud problem makes it clear how little reporting received by a digital advertiser is reliable. The intrusive behavioral targeting of users incentivizes criminal scams to defraud advertisers. The anonymized statistics you cite in your question may be considerably more robust.

Furthermore, a recent PricewaterhouseCoopers analysis of the media marketplace predicts that increased consolidation is a foregone conclusion in the podcast industry: “The podcast market is ripe for M&A activity, as potential targets in the space include content networks, hosting services, distribution platforms, and advertising and analytics services."3 Indeed, Spotify recently purchased the podcasting firms Gimlet and Anchor for a combined $340 million.

a. Do you believe that a wave of consolidation in the podcast market is inevitable?

We do not have insight in to the podcast market.

b. Why did this consolidation not take place earlier? Did Apple’s focus on privacy change the way the podcast advertising market developed?

We do not know.

4. The major digital advertising markets essentially operate as black-box auctions. Each platform runs its own internal exchange and, in the milliseconds required to load a page, makes decisions about the ads you will be served. At the same time, advertising fraud is rampant, with computer programs (bots) either creating fake traffic on websites with embedded ads or automatically generating clicks on banners. One research firm estimated that ad fraud cost advertisers $19 billion in 2018,iii the same year in which Facebook, for example, shut down 583 million fake accounts in the first quarter alone.iv Google recently agreed to refund advertisers for ads purchased on its ad marketplaces that ran on websites with fake traffic.v In addition to the trackers meant to follow us from site to site and from device to device, there are also trackers set up simply for verifying ad fraud. Thus, in effect, the watchers themselves are being watched, as companies resist paying for the delivery of ads that never reach the intended audience.

Given the lack of transparency about this process, how confident are you that this is a functioning market? How do we know that it is competitive? How do we know whether it is efficiency enhancing?

We agree that this is a dysfunctional market. Indeed, Brave wrote to Margarethe Vestager, European Commissioner for Competition, to request that she launch a sector inquiry in to market problems that disadvantage publishers and foreclose innovative entrants.32 There are several problems.

First, cross-usage of data by dominant players creates barriers to entry to innovative market entrants. We elaborate on this point in our answer to your question No. 1, above.

Second, monopsony/cartel practices in the €19.55 billion “programmatic online behavioral advertising” market disadvantage publishers. A publisher loses the ability to monetize its unique audience, and pay enormous – and generally opaque – percentages to distribution intermediaries when selling its ad space.

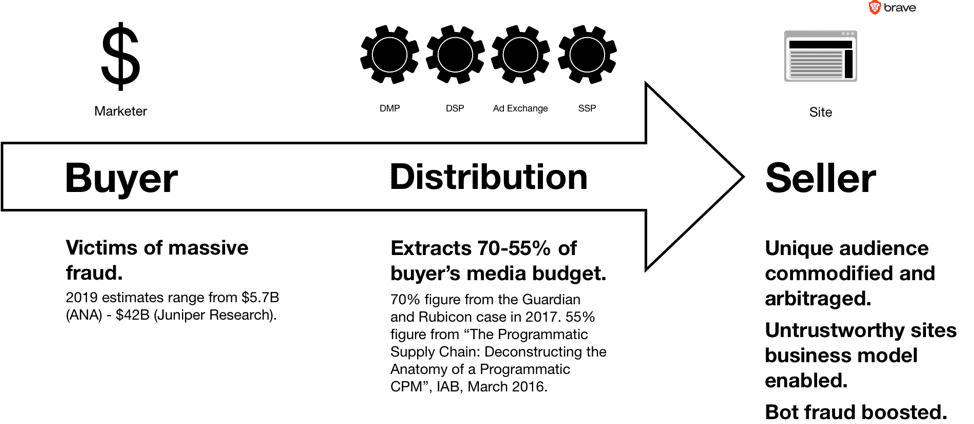

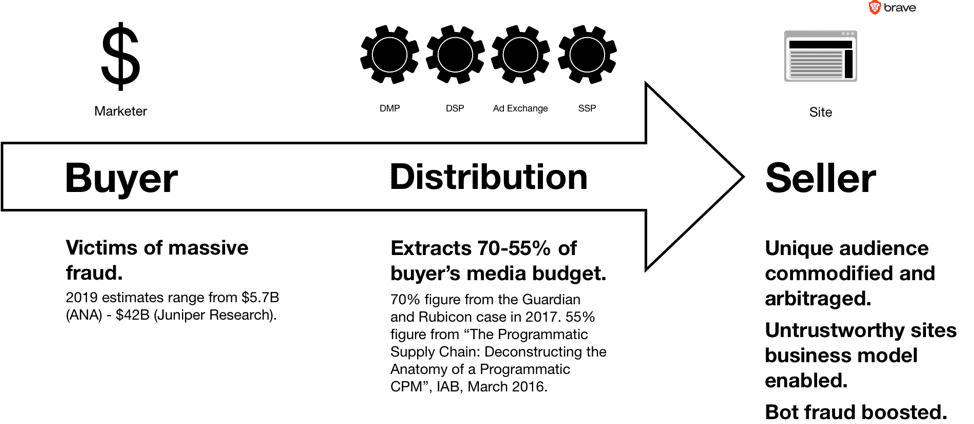

Overview of market problems in $19.55B33 real-time bidding market

In this market, publishers of websites and apps are the suppliers of people, who are needed to view advertising. Marketers, who pay for advertisements to be shown to these people, are the buyers. Advertising technology companies such as “real-time bidding ad exchanges” control distribution.

We are concerned by the degree to which concentration in the adtech sector, which controls distribution, may have created a monopsony or cartel situation, where publishers who supply advertising views are compelled to do business with a small number of highly concentrated real-time bidding advertising exchanges and systems that purchase or facilitate the purchase of their advertising space, and dictate terms.

This concerns not only Google, but also several other large participants in the market that control how the system operates.

As a part of this, we are concerned about whether publishers are required to agree to practices such as the use of unique identifiers in RTB “bid requests” that enable companies that receive these to turn each publishers’ unique audience in to a commodity that can be targeted on cheaper sites and apps. This strips a reputable publisher of their most essential asset.

We are also concerned about the degree to which “adtech” firms that control the distribution of the advertising slots supplied by web site publishers have distorted the market. 70%-55% of advertising revenue now goes to distribution “adtech” firms.34

Third, consumer harm is caused when advertising spending is diverted from content producing publishers to criminal fraudsters, the bottom of the web, and platforms that do not contribute content. The result appears to be a reduction in choice of quality content.

5. Last fall, at an FTC hearing on the economics of Big Data and personal information, Professor Alessandro Acquisti of Carnegie Mellon University previewed findings from his research indicating that targeted advertising increases revenue, but only by approximately 4 percent.35 Meanwhile, purchasing behaviorally targeted ads versus nontargeted ads is orders of magnitude more expensive. If ultimately proven true, what should advertisers do with this information?

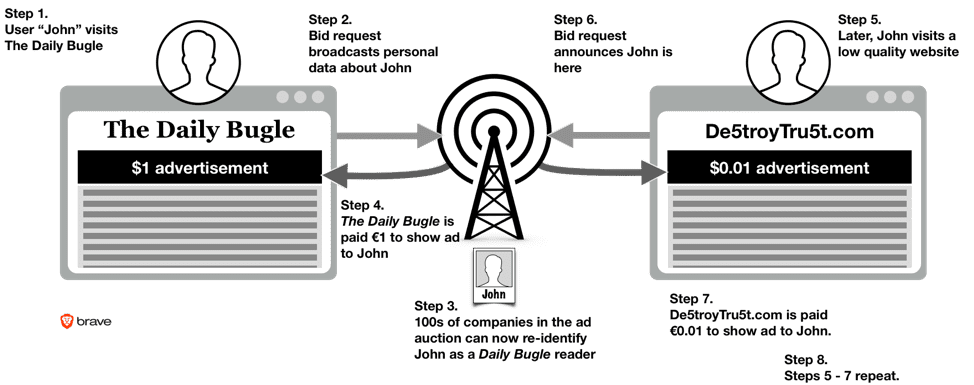

First, we believe that the reality is worse for publishers than this report suggests. This is because the study does not take account of two large costs that publishers bear: first, their audiences are commodified and arbitraged, and second, ad fraud diverts billions of dollars of advertising spending from their websites and in to the hands of criminals. The diagram below shows how these problems occur.

Audience arbitrage: how worthy publishers’ audiences are commodified.

While the Daily Bugle may net $1 the first time this occurs, it finds itself undercut by De5troyTru5t.com thereafter. Thus, the online real-time bidding advertising system commodifies worthy publishers’ unique audiences, and enables a business model for the bottom of the Web.

Example of an ad fraud scam: fake traffic bought by scam-publishers.

We believe that the current model of “broadcast behavioral” harms publishers. The way to solve this is to pressure the two standard-setting organizations that control the market: the IAB and Google, to remove personal data that enable audience arbitrage and much of the “bot fraud” problem from the system. This would also stop the real-time bidding from leakage of sensitive, profiling data about every single web user. Currently profiling data about web users is leaked in hundreds of billions of broadcasts every day.36 Making this transition at the industry standards level that affects everybody avoids individual companies facing a first mover disadvantage if they act alone (as described in the answer to question 6, below).

6. Earlier this year, rather than running the risk of incurring the large maximum fines set forth in the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the New York Times decided it would simply block all open-exchange ad buying on its European pages. What this means is that the Times completely eliminated behavioral targeting on its European sites and focused entirely on contextual and geographical targeting. Surprisingly, the Times saw no ad revenue drop as a result; in fact, quite the opposite happened—it was able to increase its ad revenue even after cutting itself off from ad exchanges in Europe. Does this episode tell us anything at all about the efficacy of behavioral targeting? Or can this outcome simply be attributed to the strength of certain brands?

The New York Times stopped broadcasting personal data in “real-time bidding” advertising auctions, because Article 5 (1) f of the GDPR forbids the broadcast of personal data without control over where the data may end up. We anticipate that a market in which all publishers make the same transition will yield far higher revenues to publishers. However, we also understand that for most publishers this is impossible to do alone. There is a first mover disadvantage, or prisoner’s dilemma: one publisher is not able to make the first move on its own for fear that its competitors will not follow suit. It will then be at a market disadvantage in the short and medium term, and may not be able to enjoy the benefit of the transition to clean data in the long term.

The likelihood is that publishers can only enjoy this benefit if they move together. And this can only happen if the two IAB and Google real-time bidding industry standards is changed, causing the transition to apply to all publishers at the same moment.

The case of the New York Times is unusual in two respects. First, only a small percentage of its revenue comes from the European market, so this was a relatively safe experiment for it to make. Second, its brand is so strong that the experiment that it took may not replicate for any other first mover. Therefore, the change has to be made at the standards level, with the IAB and Google bringing their real-time bidding systems in to compliance with the GDPR.

III. Questions from Senator Graham

1. How is the current digital advertising marketplace impacting publishers like the Wall Street Journal and New York Times? How will privacy legislation change that?

The following figures describe the main parts of the US digital advertising market: search advertising (dominated by Google) accounts for 46% ($22.8B, half year 2018 figure) of the entire US digital advertising market; social advertising (dominated by Facebook) accounts for a further 26.4% ($13.1B, half year 2018 figure);37 and a separate estimate indicates that once search and social markets are removed, real-time bidding (RTB) accounts for half (48%) of the remainder ($19.55B, full year estimate for 2018).38

The high percentage of search and social advertising spending poses acute problems for publishers for the simple reason that they are not active in that part of the market. There are also deep problems in the real-time bidding market in which these publishers do participate.

Overview of market problems in $19.55B39 real-time bidding market

As the diagram above (also copied in the answer question no. 4 from Senator Booker, above) shows, advertising buyers suffer from an enormous “adfraud” problem (see my answer to Senator Booker’s questions no. 3 and 5, above, for more on this issue).

Distribution is controlled by advertising technology companies (Google is the largest) that extract 55%-70% of every advertising dollar. Publishers of websites and apps are the sellers, but have their audiences commodified and arbitraged on low-rent sites, and suffer further from the diversion of revenue away from their sites to fake sites by ad fraud scammers.

2. As a result of GDPR, we understand that Google limited third-party ad serving on YouTube and also restricted the data received by publishers through AdSense. Do you agree with Google’s interpretation of GDPR? Could the law be clearer?

The GDPR is clearly drafted, and should be well understood because it shares much in common with pre-existing 1995 Data Protection Directive. Companies that claim that the GDPR is unclear are likely to have been unaware of, or intentionally avoiding, the responsibilities that they have borne for twenty three years, since the 1995 Directive. That Directive was weakly implemented, and gave enforcers minimal powers to sanction infringers, so ignoring data protection law became common practice. What is new in the GDPR is that companies must now seriously consider complying, because the data protection authorities and data subjects have new powers and rights to penalize infringement.

European data protection authorities have issued guidance on specific points of European data protection law since 1995. The law is both clearly drafted and clearly explained. There is very little in the Regulation that would surprise any company that already adhered to the previous 1995 Data Protection Directive as written.

We cannot comment directly on the specific case you mention, because we are not adequately familiar with it.

In more general terms, our view that that Google is indeed infringing the GDPR. Indeed, we and others have filed formal complaints under the GDPR against Google’s misuse of personal data with data protection authorities across the EU.40 The Irish Data Protection Commission appears to agree with this assessment, and announced in late May that it has launched a statutory inquiry in to infringement of the GDPR by Google’s DoubleClick/Authorized Buyer’s business under Section 110 of the Irish Data Protection Act, which deals specifically with “suspected infringement”.41 This is significant because the Irish Data Protection Commission is Google’s lead supervisory authority under the GDPR.

It is also worth noting that Google’s approach to consent has already been ruled unlawful by the French data protection authority.42

Our view, and the apparent view of Google’s lead supervisory authority under the GDPR, is that we suspect that Google is infringing the GDPR. We anticipate that it will be forced to change how it uses personal data as a result.

IV. Questions from Senator Leahy

1. Even when companies have an actual business purpose for collecting information, they sometimes sell or share that data to third parties. There is important discussion about the benefits of requiring consumer consent, but as many of these technologies have become ubiquitous in our daily lives, opting-out of data collection and sharing only becomes increasingly difficult.

a. What restrictions currently exist, if any, regarding how data brokers use consumers’ data? And what is your view on how transparent that process is for an average consumer? Are consumers even aware of what data brokers are doing?

We do not have a detailed survey of state law or sector specific law on data broker restrictions.

We call your attention to a study and formal GDPR complaints against several data brokers by Privacy International on the issue of transparency.43 It is clear that consumers are not aware of the specifics of the data broker industry. Certainly, the kind of conduct revealed in the FTC’s 2014 major report are not widely known.44 But survey data over several years demonstrates a general and widespread concern about online tracking and data collection that contributes to data brokers’ profiles. Below is a summary of survey results on both sides of the Atlantic that reveal a deep unease.

- The UK Information Commissioner’s Office’s survey, published in August 2018, reports that 53% of British adults are concerned about “online activity being tracked”.45

- In 2017, GFK was commissioned by IAB Europe (the AdTech industry’s own trade body) to survey 11,000 people across the EU about their attitudes to online media and advertising. GFK reported that only “20% would be happy for their data to be shared with third parties for advertising purposes”.46 This tallies closely with survey that GFK conducted in the United States in 2014, which found that “7 out of 10 Baby Boomers [born after 1969], and 8 out of 10 Pre-Boomers [born before 1969], distrust marketers and advertisers with their data”.47

- In 2016 a Eurobarometer survey of 26,526 people across the European Union found that:

“Six in ten (60%) respondents have already changed the privacy settings on their Internet browser and four in ten (40%) avoid certain websites because they are worried their online activities are monitored. Over one third (37%) use software that protects them from seeing online adverts and more than a quarter (27%) use software that prevents their online activities from being monitored”.48

- This corresponds with an earlier Eurobarometer survey of similar scale in 2011, which found that “70% of Europeans are concerned that their personal data held by companies may be used for a purpose other than that for which it was collected”.49

- The same concerns arise in the United States. In May 2015, the Pew Research Centre reported that:

“76% of [United States] adults say they are “not too confident” or “not at all confident” that records of their activity maintained by the online advertisers who place ads on the websites they visit will remain private and secure.”50

- In fact, respondents were the least confident in online advertising industry keeping personal data about them private than any other category of data processor, including social media platforms, search engines, and credit card companies. 50% said that no information should be shared with “online advertisers”.51

- In a succession of surveys, large majorities express concern about ad tech. The UK’s Royal Statistical Society published research on trust in data and attitudes toward data use and data sharing in 2014, and found that:

“the public showed very little support for “online retailers looking at your past pages and sending you targeted advertisements”, which 71% said should not happen”.52

- Similar results have appeared in the marketing industry’s own research. RazorFish, an advertising agency, conducted a study of 1,500 people in the UK, US, China, and Brazil, in 2014 and found that 77% of respondents thought it was an invasion of privacy when advertising targeted them on mobile.53

These concerns are manifest in how people now behave online. The enormous growth of adblocking (to 615 million active devices by the start of 2017, globally)54 demonstrates the concern that Internet users have about being tracked and profiled by the ad tech industry companies. One industry commentator has called this the “biggest boycott in history”.55

Concern about the misuse of personal data in online behavioural advertising is not confined to Internet users alone. Reputable advertisers, who pay for campaigns online, are concerned about it too. In January 2018, the CEO of the World Association of Advertisers, Stephan Loerke, wrote an opinion piece in AdAge attacking the current system as a “data free-for-all” where “each ad being served involved data that had been touched by up to fifty companies according to programmatic experts Labmatik”.56

b. What sort of transparency and disclosure rules should be included in a federal data privacy law? Is opt-in consent enough?

Consent should not be the sole means of legally using personal information. We suggest that the GDPR model is useful to follow: it requires consent in certain cases where particularly sensitive data are concerned, but also has several other “legal bases” that permit the processing of personal data. These are described in GDPR Article 6 (1). For example, if a person’s home address is required in order to deliver a product that the person has ordered, this is covered by “contractual necessity” (GDPR Article 6 (1) b), rather than consent. Other legal bases include “vital interest” (Article 6 (1) d), which allows personal data to be used “in order to protect the vital interests of the data subject or another natural person”.

In all cases, disclosure, as defined in GDPR Article 12, 13, and 14, should be required so that a person knows what is being done with their data, by who, for what reason, and what safeguards and rights apply.

c. What should consent look like and how can we ensure that consent is not given under duress? Can we expect people to opt-out when the technology we use has become central to our daily lives?

The GDPR is a useful model in this case too. Article 4 (11) of the GDPR sets out the requirements for valid consent:

"‘consent’ of the data subject means any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her”57

Article 7 (4) of the GDPR describes the test of whether consent has been freely given:

“When assessing whether consent is freely given, utmost account shall be taken of whether, inter alia, the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is conditional on consent to the processing of personal data that is not necessary for the performance of that contract.”58

Recital 42 of the GDPR observes that users should be able to “refuse or withdraw consent without detriment”. Recital 43 states:

"…Consent is presumed not to be freely given if … the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is dependent on the consent despite such consent not being necessary for such performance.”

In short, the GDPR approach is to prohibit “forced consent”. We believe this is a sensible approach. It is worth noting that Google, Facebook, and the IAB all face formal GDPR complaints because they infringe this prohibition (see answer to Senator Whitehouse’s question No. 1, above, for elaboration on IAB “forced consent”).

2. Up to this point, a number of states have lived up to their “laboratories of democracy” moniker and led the way in regulating data privacy. One of the biggest issues surrounding a potential federal consumer data privacy law is preemption.

a. Do you believe that Congress should write “one national standard” that wipes out state legislation like California’s Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), Illinois’ Biometric Privacy Act, and Vermont’s Data Broker Act, or should the federal bill create a minimum standard that allows states to include additional protections on top of it?

A federal law of an equal or higher standard than state laws is necessary to restore trust and protect the online industry in the United States. We are of the firm view that a US federal law should use common definitions to those used in the GDPR.

The standard of protection in a federal privacy law, and the definition of key concepts and tools in it, should be compatible and interoperable with the emerging GDPR de facto standard that is being adopted globally. This includes concepts such as “personal data”, opt-in “consent”, “profiling”, and tools such as “data protection impact assessments”, and “records of processing activities”. A federal GDPR-like standard would reduce friction and uncertainty, and avert the prospect of isolation for United States companies.

b. Do you believe that any federal privacy standard should, at a minimum, meet the existing consumer protections set by the states, noted above, that have thus far led the way?

Yes.

Notes

- [1]: “The EU’s proposed new cookie rules”, attached to email from Townsend Feehan, IAB Europe’s CEO, to senior personnel at the European Commission Directorate General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, 26 June 2017, submitted in evidence to the Irish Data Protection Commission, and UK Information Commissioner’s Office, 20 February 2019 (URL: https://fixad.tech/february2019/).

- [2]: “Pubvendors.json”, IAB Europe, May 2018, submitted in evidence to the Irish Data Protection Commission, and UK Information Commissioner’s Office, 20 February 2019 (URL: https://fixad.tech/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2-pubvendors.json-v1.0.pdf), p. 5.

- [3]: The GDPR, Article 5 (1) b, and note reference to the principle of “purpose limitation”. See also Recital 43. For more on the purpose limitation principle see “Opinion 03/2013 on purpose limitation”, Article 29 Working Party, 2 April 2013.

- [4]: “IAB Europe Transparency & Consent Framework – Policies Version 2019- .3 – Draft for public comment”, IAB Europe, 25 April 2019 (URL: https://www.iabeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Draft-for-public-comment-of-Transparency-Consent-Framework-Policies-Version-2019-XX-XX.3.pdf), pp 21-29.

- [5]: Note that the Article 29 Working Party very recently warned that this alone might be enough to render consent invalid: “when the identity of the controller or the purpose of the processing is not apparent from the first information layer of the layered privacy notice (and are located in further sub-layers), it will be difficult for the data controller to demonstrate that the data subject has given informed consent, unless the data controller can show that the data subject in question accessed that information prior to giving consent”. See also “IAB Europe Transparency & Consent Framework – Policies Version 2019- .3 – Draft for public comment”, IAB Europe, 25 April 2019 (URL: https://www.iabeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Draft-for-public-comment-of-Transparency-Consent-Framework-Policies-Version-2019-XX-XX.3.pdf), pp 45-46. Quote from “Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679”, WP259, Article 29 Working Party, 28 November 2017 (URL: https://pagefair.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/wp259_enpdf.pdf), p. 15, footnote 39.

- [6]: See discussion of data processing purposes in online behavioral advertising, and the degree of granularity required in consent, in “GDPR consent design: how granular must adtech opt-ins be?”, PageFair Insider, January 2018 (URL: https://pagefair.com/blog/2018/granular-gdpr-consent/).

- [7]: “Transparency & Consent Framework FAQ”, IAB Europe, 8 March 2018, p. 18.

- [8]: “Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679”, WP259, Article 29 Working Party, 28 November 2017, p. 11.

- [9]: The GDPR, Article 6 (1) a.

- [10]: The GDPR, Article 13, paragraph 2, f, and Recital 60.

- [11]: “Transparency & Consent Framework FAQ”, IAB Europe, 8 March 2018, p. 18.

- [12]: “IAB Europe Transparency & Consent Framework – Policies Version 2019- .3 – Draft for public comment”, IAB Europe, 25 April 2019 (URL: https://www.iabeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Draft-for-public-comment-of-Transparency-Consent-Framework-Policies-Version-2019-XX-XX.3.pdf), p. 22.

- [13]: “IAB Europe Transparency & Consent Framework – Policies Version 2019- .3 – Draft for public comment”, IAB Europe, 25 April 2019 (URL: https://www.iabeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Draft-for-public-comment-of-Transparency-Consent-Framework-Policies-Version-2019-XX-XX.3.pdf), p. 13.

- [14]: “Transparency & Consent Framework, Cookie and Vendor List Format, Draft for Public Comment, v1.a”, IAB Europe, p. 5. This is apparently “due to concerns of payload size and negatively impacting the consumer experience, a per-vendor AND per-purpose option is not available”, p. 22.

- [15]: “IAB Europe Transparency & Consent Framework – Policies Version 2019- .3 – Draft for public comment”, IAB Europe, 25 April 2019 (URL: https://www.iabeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Draft-for-public-comment-of-Transparency-Consent-Framework-Policies-Version-2019-XX-XX.3.pdf), pp 45-46.

- [16]: The Regulation is clear that “consent should not be regarded as freely given if the data subject has no genuine or free choice”. The GDPR, Recital 42. See also, Article 4, paragraph 11.

- [17]: Formal GDPR complaint against IAB Europe’s “cookie wall” and GDPR consent guidance., Brave, 1 April 2019 (URL: /blog/iab-cookie-wall/).

- [18]: Complaint by Dr Johnny Ryan against IAB Europe’s unlawful cookie wall. Ibid.

- [19]: GDPR, Article 13.

- [20]: “Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679”, Article 29 Working Party, 28 November 2017, p. 14.

- [21]: GDPR, Article 4 (11), and Recital 32.

- [22]: “Guidelines on transparency under Regulation 216/679” Article 29 Working Party, November 2017, pp 8, 13.

- [23]: GDPR, Article 7 (3).

- [24]: “Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679”, Article 29 Working Party, 28 November 2017, p. 14.

- [25]: “Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679”, Article 29 Working Party, 28 November 2017, p. 15.

- [26]: GDPR, Article 9 (2) a.

- [27]: “Guidelines on consent under Regulation 2016/679”, Article 29 Working Party, 28 November 2017, p. 19.

- [28]: In late 2018, Google modified its market-leading Chrome browser, so that users would automatically be signed in to the browser when they use any individual Google service. They would also be opted in to all Google tracking, including through the use of cookies that the update to Chrome made it impossible to delete. This modification tied whatever particular service the user had actually signed in to the “signed in” version of Chrome, and to the rest of Google’s products as well. Further, this modification also enabled the cross-use of the user’s data from the specific service that the user had signed in to in a way that advantages Google’s position in every other line of business too. Following a popular outcry, Google announced a partial reversal of the modification: the next update to the Chrome browser would continue to automatically sign users in to the browser and to all of Google, but would also provide a mechanism to opt-out for those users adventurous enough to find it. See Zach Koch, “Product updates based on your feedback”, The Keyword [Google blog], 26 September 2018 (URL: https://www.blog.google/products/chrome/product-updates-based-your-feedback/).

- [29]: As with many of the principles of the GDPR, this is based on the FIPPs of the 1974 US Privacy Act.

- [30]: Consider for example the act of posting a photo on the Facebook Newsfeed for the first time. The distinct processing purposes involved might be something like the following list. The person posting the photo is only interested only the first four or five of these purposes. – To display your posts on your Newsfeed. – To display posts on tagged friends’ Newsfeeds. – To display friends posts that tag you on your Newsfeed. – To identify untagged people in your posts. – To record your reaction to posts to refine future content for you, which may include ethnicity, politics, sexuality, etc…, to make our Newsfeed more relevant to you. – To record your reaction to posts to refine future content for you, which may include ethnicity, politics, sexuality, etc…, to make ads relevant to you. – To record your reaction to posts to refine future content for you, which may include ethnicity, politics, sexuality, etc…, for advertising fraud prevention.

- [31]: “Facebook has disabled almost 1.3 billion fake accounts over the past six months”, Recode, 15 May 2018 (URL: https://www.vox.com/2018/5/15/17349790/facebook-mark-zuckerberg-fake-accounts-content-policy-update); and “Facebook Removes 3 Billion Fake Accounts”, Markets Insider, 23 May 2019 (URL: https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/facebook-removes-3-billion-fake-accounts-1028227191).

- [32]: “Brave requests European Commission antitrust examination of online ad market”, Brave Insight, 4 December 2018 (URL: /blog/european-commission-sector-inquiry/)

- [33]: “More than 80 of digital display ads will be bought programmatically in 2018”, eMarketer, 9 April 2018 (URL: https://www.emarketer.com/content/more-than-80-of-digital-display-ads-will-be-bought-programmatically-in-2018).

- [34]: 70% figure from the investigation by The Guardian, which purchased advertising on its own web site as a buyer, and received only 30% of its spend as a supplier. See “Where did the money go? Guardian buys its own ad inventory”, Mediatel Newsline, 4 October 2016 (URL: https://mediatel.co.uk/news/2016/10/04/where-did-the-money-go-guardian-buys-its-own-ad-inventory/). 55% figure from “The Programmatic Supply Chain: Deconstructing the Anatomy of a Programmatic CPM”, IAB, March 2016 (URL: https://www.iab.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Programmatic-Value-Layers-March-2016-FINALv2.pdf).

- [35]: FTC Hearing 6 – Nov. 6 Session 2 – The Economics of Big Data and Personal Information, FED. TRADE COMM’N (Nov. 6, 2018) (URL: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/audio-video/video/ftc-hearing-6-nov-6-session-2-economics-big-data-personal-information).

- [36]: “Bid request scale overview”, submitted in evidence to the Irish Data Protection Commission, and UK Information Commissioner’s Office, 20 February 20119 (URL: https://fixad.tech/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/4-appendix-on-market-saturation-of-the-systems.pdf).

- [37]: “IAB internet advertising revenue report, half year 2018 and Q2 2018”, IAB, November 2018 (URL: https://www.iab.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/IAB-WEBINAR-HY18-Internet-Ad-Revenue-Report1.pdf), p. 24.

- [38]: “US ad spending 2018: updated forecast for digital and traditional media ad spending”, eMarketer, 16 October 2018 (URL: https://www.emarketer.com/content/us-ad-spending-2018); and “More than 80 of digital display ads will be bought programmatically in 2018”, eMarketer, 9 April 2018 (URL: https://www.emarketer.com/content/more-than-80-of-digital-display-ads-will-be-bought-programmatically-in-2018).

- [39]: “More than 80 of digital display ads will be bought programmatically in 2018”, eMarketer, 9 April 2018 (URL: https://www.emarketer.com/content/more-than-80-of-digital-display-ads-will-be-bought-programmatically-in-2018).

- [40]: “Regulatory complaint concerning massive, web-wide data breach by Google and other “ad tech” companies under Europe’s GDPR”, Fixad.tech, 12 September 2018 (URL: https://fixad.tech/september2018/).

- [41]: “Data Protection Commission opens statutory inquiry into Google Ireland Limited”, Data Protection Commission, 22 May 2019 (URL: https://www.dataprotection.ie/en/news-media/press-releases/data-protection-commission-opens-statutory-inquiry-google-ireland-limited).

- [42]: “Délibération n°SAN-2019-001 du 21 janvier 2019 Délibération de la formation restreinte n° SAN – 2019-001 du 21 janvier 2019 prononçant une sanction pécuniaire à l’encontre de la société GOOGLE LLC”, Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, 21 January 2019 (URL: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichCnil.do?oldAction=rechExpCnil&id=CNILTEXT000038032552&fastReqId=2103387945&fastPos=1).

- [43]: “Privacy International files complaints against seven companies for wide-scale and systematic infringements of data protection law”, Privacy International, 8 November 2018 (URL: https://privacyinternational.org/press-release/2424/press-release-privacy-international-files-complaints-against-seven-companies).

- [44]: “Data brokers: a call for transparency and accountability”, May 2014, Federal Trade Commission.

- [45]: “Information rights strategic plan: trust and confidence”, Harris Interactive for the Information Commissioner’s Office, August 2018, p. 21.

- [46]: “Europe online: an experience driven by advertising. Summary results”, IAB Europe, September 2017 (URL: http://datadrivenadvertising.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/EuropeOnline_FINAL.pdf), p. 7.

- [47]: “GFK survey on data privacy and trust: data highlights”, GFK, July 2015, p. 29.

- [48]: “Eurobarometer: e-Privacy (Eurobarometer 443)”, European commission, December 2016 (URL: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/screen/home), p. 5, 36-7.

- [49]: “Special Eurobarometer 359: attitudes on data protection and electronic identity in the European Union”, European Commission, June 2011, p. 2.

- [50]: Mary Madden and Lee Rainie, “Americans’ view about data collection and security”, Pew Research Center, May 2015 (URL: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2015/05/Privacy-and-Security-Attitudes-5.19.15_FINAL.pdf), p. 7.

- [51]: Mary Madden and Lee Rainie, “Americans’ view about data collection and security”, Pew Research Center, May 2015 (URL: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2015/05/Privacy-and-Security-Attitudes-5.19.15_FINAL.pdf), p. 25.

- [52]: “The data trust deficit: trust in data and attitudes toward data use and data sharing”, Royal Statistical Society, July 2014, p. 5.

- [53]: Stephen Lepitak, “Three quarters of mobile users see targeted adverts as invasion of privacy, says Razorfish global research”, The Drum, 30 June 2014 (URL: https://www.thedrum.com/news/2014/06/30/three-quarters-mobile-users-see-targeted-adverts-invasion-privacy-says-razorfish).

- [54]: “The state of the blocked web: 2017 global adblock report”, PageFair, January 2017 (https://pagefair.com/downloads/2017/01/PageFair-2017-Adblock-Report.pdf).

- [55]: Doc Searls, “Beyond ad blocking – the biggest boycott in human history”, Doc Searls Weblog, 28 September 2015 (https://blogs.harvard.edu/doc/2015/09/28/beyond-ad-blocking-the-biggest-boycott-in-human-history/).

- [56]: Stephan Loerke, “GDPR data-privacy rules signal a welcome revolution”, AdAge, 25 January 2018 (URL: https://adage.com/article/cmo-strategy/gdpr-signals-a-revolution/312074).

- [57]: GDPR Article 4 (11).

- [58]: GDPR Article 4 (7).

End notes included in Senators’ questions.

- [i]: Tim Wu, Tech Dominance and the Policeman at the Elbow (Columbia Pub. Law Research Paper No. 14- 623, 2019), https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2289.

- [ii]: Matthew Yglesias, The Justice Department Was Absolutely Right To Go After Microsoft in the 1990s, SLATE (Aug. 26, 2013), https://slate.com/business/2013/08/microsoft-antitrust-suit-the-vindication-of-the-justice-department.html. 3 Bart Spiegel, Ian Same & Silpa Velaga, US Media and Telecommunications Deals insights Q1 ‘19, PWC (2019), https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/power-utilities/pdf/pwc-media-and-telecom-deals-insights-q1-2019.pdf

- [iii]: Ad Fraud To Cost Advertisers $19 Billion in 2018, Representing 9% of Total Digital Advertising Spend, JUNIPER RESEARCH (Sept. 26, 2017), https://www.juniperresearch.com/press/press-releases/ad-fraud-to-cost-advertisers-$19-billion-in-2018.

- [iv]: Alex Hern & Olivia Solon, Facebook Closed 583m Fake Accounts in First Three Months of 2018, GUARDIAN (May 15, 2018), https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/may/15/facebook-closed-583m-fake-accounts-in-first-three-months-of-2018.

- [v]: Patience Haggin, Google To Refund Advertisers After Suit over Fraud Scheme, WALL ST. J. (May 17, 2019), https://www.wsj.com/articles/google-to-refund-advertisers-after-suit-over-fraud-scheme-11558113251.