Brave alerts the FTC about two major problems in digital media & services markets

Brave has alerted the Federal Trade Commission about major problems in the digital media and services market. We have also recommended key actions.

Brave’s 2,500 word submission warns the FTC about two critical hazards for the US digital market.

First, big tech companies “cross-use” user data from one part of their business to prop up others. This stifles competition, and hurts innovation and consumer choice. Brave suggests that FTC should investigate.

Second, the GDPR is emerging as a de facto international standard. Whether this helps or harms United States firms will be determined by whether the United States enacts and actively enforces robust federal privacy laws.

The submission is a response to the FTC’s call for submissions regarding competition and consumer protection in the 21st Century.

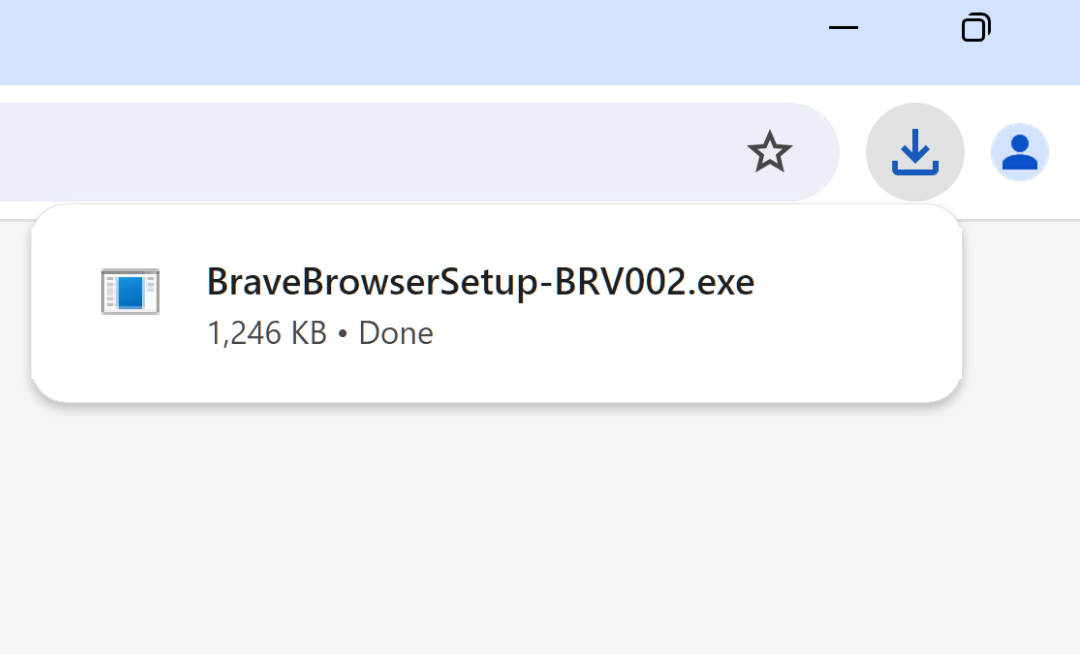

The full text of Brave’s submission is copied below. You can download the PDF here.

Donald S. Clark, Secretary of the Commission

Federal Trade Commission

Office of the Secretary

600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW

Suite CC-5610 (Annex C)

Washington, DC 20580

7 January 2019

Docket FTC-2018-0100:

Hearing 6 on Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century

Dear Mr Clark,

I represent Brave, a rapidly growing technology company that financially supports websites and protects privacy online. Brave is at the cutting edge of the online media industry. Our CEO, Brendan Eich, is the inventor of JavaScript, and co-founded Mozilla/Firefox. Brave is headquartered in San Francisco, and our employees work on key technologies such as machine learning, blockchain, and security. We work with partners across the online media and advertising industry, and have developed a form of private online advertising that protects consumers from “adtech” surveillance.

The Commission has requested comment on the Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century Hearings. This letter responds to three particularly important questions issued by the Commission regarding hearing 6 on “Privacy, Big Data, and Competition”:

- How dominant companies cross-use data to stifle competition (our response to FTC question 6).

- The impact of the GDPR (our response to FTC question 7).

- Brave’s recommendations on

i) the character of a future United States federal law built on the GDPR that could protect innovation, competition, and consumer welfare; and

ii) the value of “purpose specification” as an antitrust analysis and enforcement tool

(our response to FTC question 5).

Response to question 6.

Do the presence of personal information or privacy concerns inform or change competition analysis?

The presence of personal information has two likely impacts that bear consideration:

First impact: cross-use and offensive leveraging of personal information.

The cross-use and offensive leveraging of personal information from one line of business to another is likely to have anti-competitive effects. Indeed anti-competitive practices may be inevitable when companies with Google’s degree of market dominance update their privacy policies to include the cross-use of personal information.1

The result is that a company can leverage all the personal information2 accumulated from its users in one line of business to dominate other lines of business too. Rather than competing on the merits, the company can enjoy the unfair advantage of massive network effects even though it may be starting from scratch in a new line of business. The result is that nascent and potential competitors will be stifled, and consumer choice will be limited.

Competition authorities in other jurisdictions have addressed this matter. As early as 2010, France’s Autorité de la concurrence highlighted the topic (in Opinion 10-A-13 on the cross-usage of customer databases). In 2015, Belgium’s regulator fined the Belgian National Lottery for reusing personal information acquired through its monopoly for a different, and incompatible, line of business.

The cross-use of data between different lines of business is analogous to the tying of two products. Indeed, tying and cross-use of data can occur at the same time, as Google Chrome’s latest “auto sign in to everything” controversy illustrates.3

Where the processing of personal information confers competitive advantage, it does not seem desirable that network effects derived from one line of business should inevitably translate to network effects in another. This should inform competition analysis.

Second impact: higher relative value of personal information, and degrees of flexibility in how data can be applied.

It may be inadequate to only count the quantity of “big data” available to a firm when analyzing the value of a firm’s assets and power. Not all data are of equal value. Therefore, we suggest that there are two additional factors that are important to consider:

Calculating the quantity of big data alone, without considering whether some of all of the data are personal information or non-personal information, is unlikely to produce an accurate value. Personal information conveys more useful insights about consumers, and is also likely to be scarcer than non-personal information because its collection often requires that consumers have indicated their consent in some manner, or have not exercised an opt-out. This scarcity is likely to increase if additional privacy and data protections are introduced at state or federal level.

A calculation of the value of these data should also consider the breadth of things for which this information can be used (although there is a proviso to this). The “Fair Information Practice Principles” of the 1974 United States Privacy Act set out a principle of “purpose specification”, providing that a person must be able “to prevent information about him that was obtained for one purpose from being used or made available for other purposes without his consent”. This principle is a common feature of privacy and data protection regimes,4 and generally prevents firms from using personal information for purposes other than those they were collected for. However, since purpose specification is nebulous in the United States, the proviso is that that the analysis of a firm’s big data includes its holdings in jurisdictions where robust purpose specification applies, or that purpose specification is further defined in the United States, as we recommend in a response to question 5, below.

Response to question 7.

How do state, federal, and international privacy laws and regulations, adopted to protect data and consumers, affect competition, innovation, and product offerings in the United States and abroad?

A de facto international standard appears to be emerging, based on the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. In the coming years, the application of GDPR-like laws for commercial use of consumers’ personal data in the EU, Britain (post EU), Japan, India, Brazil, South Korea, Malaysia, Argentina, and China bring more than half of global GDP under a common standard.

Whether this emerging standard helps or harms United States firms will be determined by whether the United States enacts and actively enforces robust federal privacy laws. Unless there is a federal GDPR-like law in the United States, there may be a degree of friction and the potential of isolation for United States companies.

However, there is an opportunity in this trend. The United States can assume the global lead by adopting the emerging GDPR standard, and by investing in world-leading regulation that pursues test cases, and defines practical standards. Cutting edge enforcement of common principles-based standards is de facto leadership.

Response to question 5.

Are there policy recommendations that would facilitate competition in markets involving data or personal or commercial information that the FTC should consider?

Because a federal law may be in prospect, the following recommendations are presented in to two separate sections. The first concerns the character of a future federal law, and how this might best protect innovation, competition, and consumer welfare. The second presents recommendations that apply irrespective of whether a federal law is introduced.

1. Recommendations on the character of a future federal law, and how this might best protect innovation, competition, and consumer welfare.

i. Brave advocates a federal law of an equal or higher standard than state laws, and suggests that such a law should be closely modeled on the GDPR. The GDPR is compatible with a United States view of consumer protection and privacy principles. Indeed, the FTC has proposed important privacy protections to legislators in 2009, and again in 2012 and 2014, which ended up being incorporated in the GDPR.

The high-level principles of the GDPR are closely aligned, and often identical to, the United States’ privacy principles. For example, the NTIA’s intended privacy outcomes are incorporated in the GDPR, as are the “Fair Information Practice Principles” of the United States Privacy Act. The GDPR also incorporates principles endorsed by the United States in the 1980 OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data; and the principles endorsed by the United States this year, in Article 19.8 (3) of the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement.

The GDPR differs from established United States privacy principles in its explicit reference to “proportionality” as a precondition of data use, and in its more robust approach to data minimization and to purpose specification. In our view, a federal law should incorporate these elements too. We also recommend that federal law should adopt the GDPR definitions of concepts such as “personal data”, “legal basis” including opt-in “consent”, “processing”, “special category personal data”, “profiling”, “data controller”, “automated decision making”, “purpose limitation”, and so forth, and tools such as data protection impact assessments, breach notification, and records of processing activities.

ii. In keeping with the fair information practice principles (FIPPs) of the 1974 US Privacy Act, Brave recommends that a federal law should require that the collection of personal information is subject to purpose specification. This means that personal information shall only be collected for specific and explicit purposes. Personal information should not used beyond those purposes without consent, unless a further purpose is poses no risk of harm and is compatible with the initial purpose, in which case the data subject should have the opportunity to opt-out.

This allows for a consideration of harms that may be suffered by the data subject, and, for example, should rule out the wide cross-use of personal information by Equifax, Facebook, Google, and other serial data protection offenders. Note also that where sensitive personal information is concerned, opt-in consent is required for all purposes, compatible or not, unless the data have been made “manifestly public” by the person that they concern.

Brave also recommends that a federal law should include a definition of what a “processing purpose” is. We propose the following definition:

A processing purpose – The term “processing purpose” means an adequately specific and granular reason for which a covered entity processes personal information. A purpose is adequately granular if there is no more granular processing purpose that can be communicated to an individual.

iii. We suggest that introducing robust opt-in consent and robust purpose specification can prevent dominant companies from foreclosing competition in the market. If purpose limitation is enforced, then dominant companies would not be able to stifle competition by acquiring nascent and potential competitors. This is because the acquired firms’ data could no longer be blended with data held by acquirers for diverse processing purposes.

2. Recommendations that apply irrespective of whether a federal law is introduced.

i. We recommend that the Commission litigate to set rules regarding purposes, using unfairness as its grounds for action. Section 5 of the FTC Act declares unfair and deceptive acts and practices unlawful, and established the test that such acts “causes or [are] likely to cause substantial injury to consumers”, which is “not reasonably avoidable by consumers”. Purpose specification protects a consumer’s opportunity to choose what to opt-in to, and forbids a company from automatically opt-ing a person in to all of its services and tracking. The unfair conflation of data purposes, and cross-use of data, make it impossible for consumers to make informed choices, and expose sensitive information about them, such as their location and private browsing habits, that can disadvantage them in several important respects including fraud, invasion of privacy, disclosure of sensitive information about them in a breach or otherwise, erosion of trust, weakened bargaining position, manipulation, and ultimately a limit of the choice available to them in the market as a result of offensive leveraging of personal information.

ii. We recommend that the Commission use purpose specification as a tool to analyze data-driven firms. A complex business that relies on data to operate can be analyzed by itemizing the following, for every data processing purpose: the specific purpose, the personal information it applies to, and the legal justification of the use of that personal information for that specific purpose. Provided a granular definition of purpose is adopted, this is a forensic method to build a detailed understanding of complex digital firms’ operations. It also enables an examiner to determine whether the use of particular data for particular purposes is permissible, and if personal information is being cross-used and offensively leveraged. This is important, because the cross-use of data is a serious antitrust concern. Young, innovative companies can be snuffed by giant incumbents who erect barriers to entry by cross-using data for purposes beyond what they were initially collected for.

iii. We recommend that the Commission explore using purpose specification as a “soft break up” tool. The Commission can correct anticompetitive data advantage without breaking up the company. By acting against unfair conflation of purposes that should be separate, the Commission can force incumbents to compete in each new line of business on the merits alone, rather than on the basis of leveraged data accrued by virtue of their dominance in other lines of business. For large digital firms with many distinct services, which may or tied or presented as a suite, this may be a powerful tool to prevent them from shutting down competition.

Conclusion

We are at your disposal to discuss these responses, and to would welcome the opportunity to brief the Commission on how greater privacy protections and antitrust regulation can benefit the online media and advertising market and consumers.

Sincerely,

Dr Johnny Ryan FRHistS

Chief Policy & Industry Relations Officer

Brave