Brave has written to the California Department of Justice to highlight potential loopholes in the California Consumer Protection Act (CCPA).

Brave is concerned about four potential loopholes in the CCPA. First, the definition of “personal information” appears to be too narrow. Second, loopholes on deletion of data may undermine the intention of the Act. Third, exceptions for “business purposes” appear to be too wide. Fourth, the concept of “sale” of data may be too narrow. This letter urges the Attorney General to consider these issues in his preliminary rulemaking.

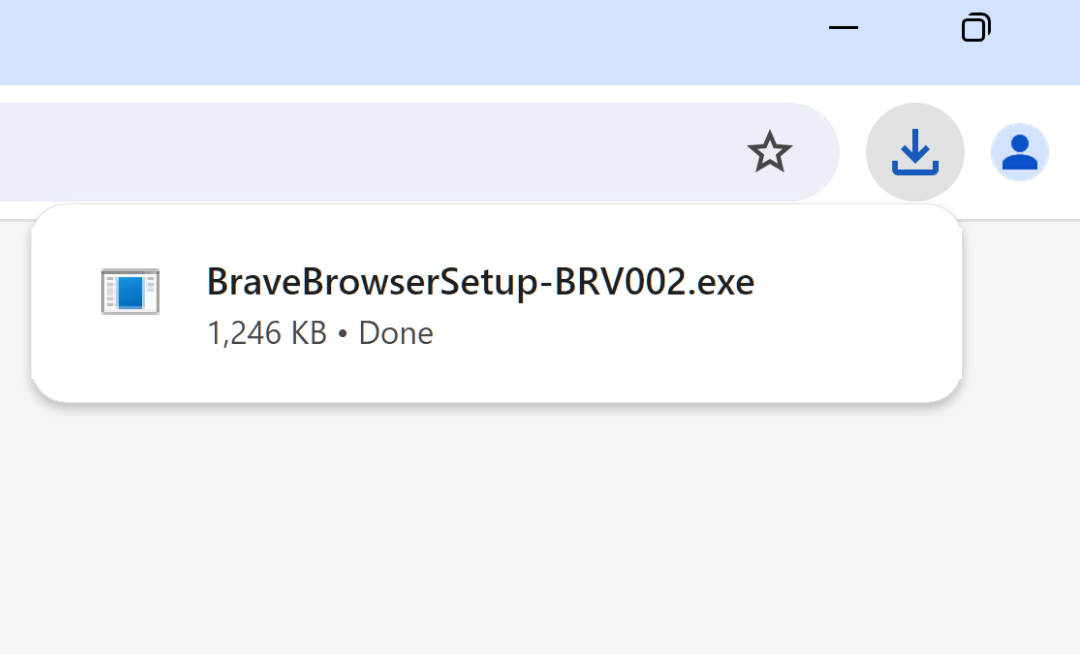

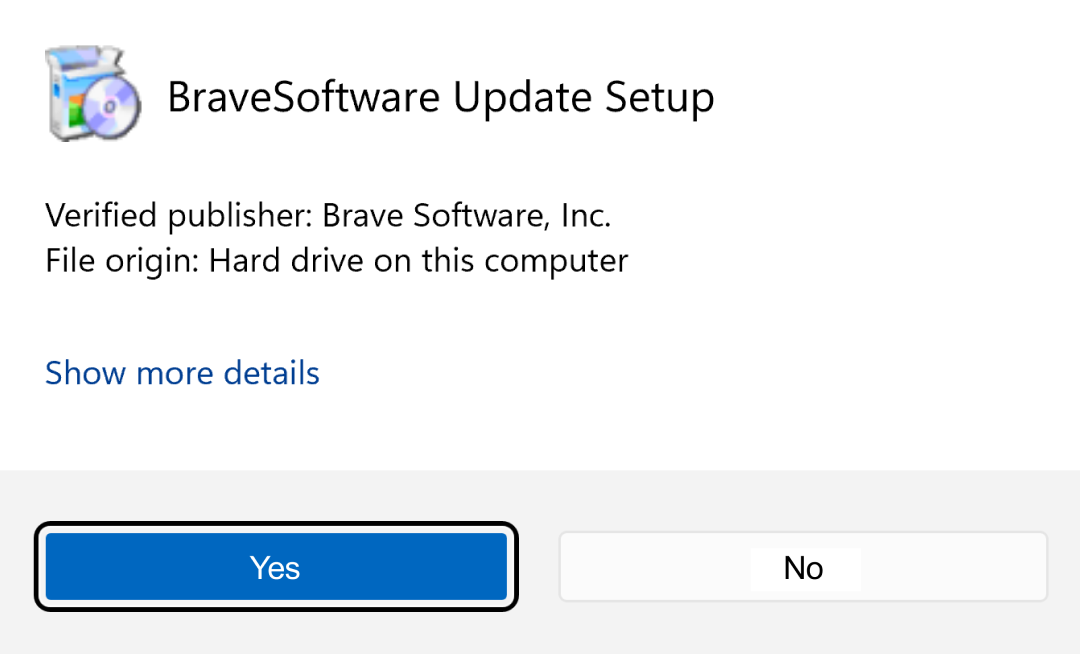

The full text of Brave’s submission is copied below. You can download the PDF here.

Privacy Regulations Coordinator

California Department of Justice

300 S. Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90013

8 March 2019

Comments on preliminary rulemaking for the California Consumer Privacy Act

Dear colleagues,

I represent Brave, a rapidly growing Internet browser based in San Francisco. Brave is at the cutting edge of the online media industry. Its CEO, Brendan Eich, is the inventor of JavaScript, and co-founded Mozilla/Firefox. Brave is headquartered in San Francisco and innovates in areas such as online advertising, machine learning, blockchain, and security.

We are heartened to see the potential increase in the level of privacy protection in the California Consumer Protection Act. We write to raise four matters, and suggest how to further protect individuals’ privacy in a manner that is compatible with innovation and economic growth.

1. “Personal information”

First, we are concerned by the fact that the definition of “personal information” does not include publicly available information. This is only partly remedied by the caveat that

“Information is not ‘publicly available’ if that data is used for a purpose that is not compatible with the purpose for which the data is maintained and made available in the government records or for which it is publicly maintained.”

We suggest that it would be simpler and easier for business to understand, and for the Attorney General to enforce, a definition of personal information that includes all personal information, irrespective of whether the information is public or not. From our perspective as a business that also operates in Europe under the GDPR, we have experienced no ill effect from the GDPR’s definition of personal data, which include both public and non-public information. As a general principle, it is the information’s relationship to a person that makes it “personal”, and this applies whether or not that information happens to also be public.

We commend the legislator for including “capable of being associated with” within the definition. This is of critical importance.

2. Deletion requests

There is a risk that the CCPA allows a business to deny a deletion request if the data concerned are – in its own judgement – useful for “security”, “debugging”, or to provide a good or service “reasonably anticipated within the context of a business’s ongoing business relationship with the consumer”.

We suggest that this is too wide a spectrum of reasons to not comply with a person’s request for deletion of information about them selves.

In particular, we are troubled by the exception concerning “a business’s ongoing business relationship with the consumer”. Why would a person request the deletion of data that would negatively affect the service they receive, unless they are aware of that fact? If, however, they are not aware of the consequences, then surely all that is necessary is to inform them, and ask if they wish to proceed. We believe that limiting a person’s right to have data about them deleted in such a circumstance run counter to logic. We are deeply concerned that this may undermine intention of the Act.

3. “Business purposes” exception

We are troubled by the Act’s exception for personal information to be used or shared when necessary to perform a “business purpose”. A business purpose can include:

“…providing advertising or marketing services, providing analytic services, or providing similar services on behalf of the business or service provider.”

We suggest that this requires more thought in the light of successive privacy scandals in advertising. Permitting personal information to be used for a business purpose that includes advertising may, we fear, open the door to widespread abuse by the advertising technology industry. As participants in this industry, we urge you to engage in rulemaking that mitigates this grave threat.

4. “Sale”

We are concerned that the concept of the “sale” of personal information may be too permissive. One company can share personal information with one or more other companies and benefit from this sharing without there being a formally defined valuable consideration. This occurs, for example, in the “real-time bidding” online ad auction system, where personal information is shared among thousands of companies. We fear that this activity would not be captured by the concept of “selling”. This is a grave concern, because real-time bidding currently broadcasts what every person in California reads, watches, and listens to online billions of times a day. Therefore, we urge a broadening of the definition of “sale” so that this activity, and similar activities, are captured.

We commend you for your work on this Act so far, and are ready to help you if we can.

Sincerely,

Dr Johnny Ryan FRHistS

Chief Policy & Industry Relations Officer